Full Article

about Lobras

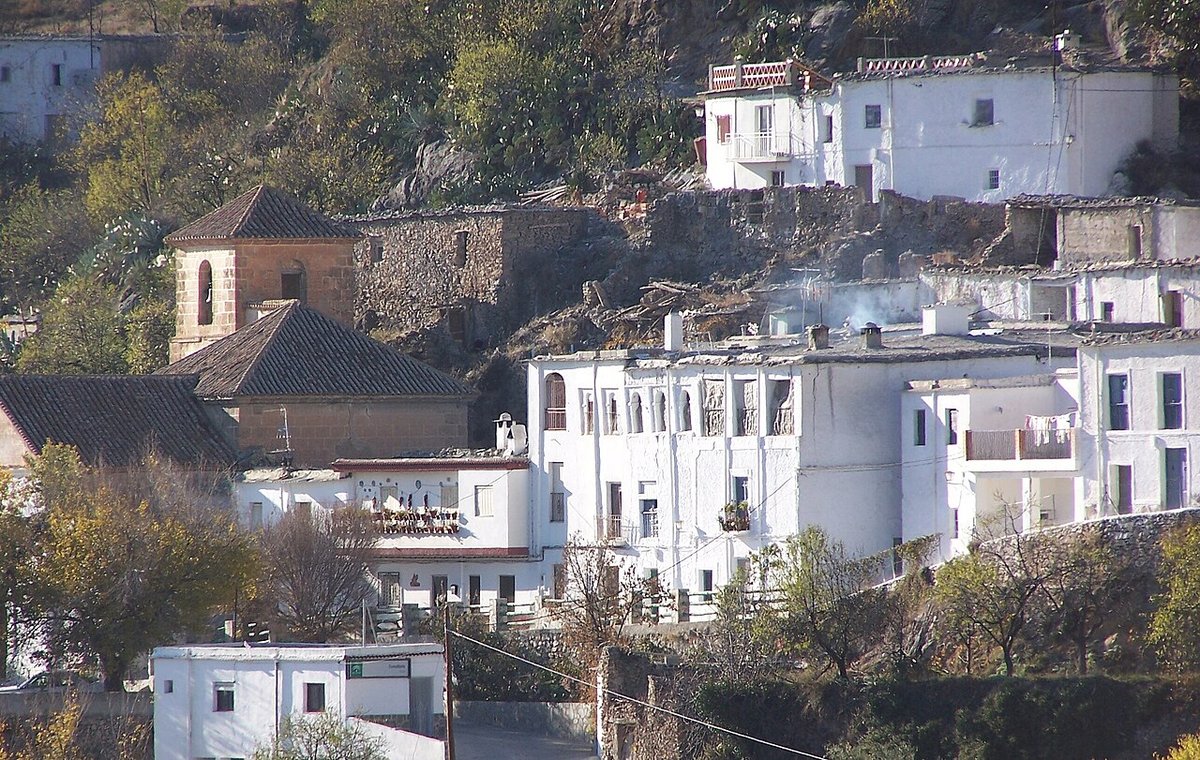

One of the smallest, quietest villages; noted for its traditional architecture and the hamlet of Tímar with its mines.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The single-track road into Lobras climbs so steeply that second gear feels ambitious. Suddenly the white houses stop clinging to the slope and spill onto a tiny square. A man in overalls is hosing the dust off yesterday’s harvest of almonds; the water runs ochre into the gutter. You have arrived 935 m above sea level, 25 minutes after leaving Granada’s ring road yet light-years away from the city’s traffic fumes.

A village that never bothered with a bypass

Lobras keeps its history in the walls, not in guidebooks. The street plan is still the one the Nasrids sketched eight centuries ago: narrow lanes that twist to break the mountain wind, sudden tinaos (tunnel-passages) where you step from sunshine into cool shadow, flat roofs pitched to catch every drop of rain. Houses are whitewashed but not prettified—paint ends where the brush ran out, revealing earlier blues and pinks like seaside weatherboarding. Look up and you’ll see Sierra Nevada’s ridgeline framed between chimney pots; look down and your eye follows centuries-old dry-stone terraces dropping towards the Guadalfeo valley, each wall built to hold back exactly one mule-width of soil.

The only monument in town is the sixteenth-century church of San Sebastián. It is smaller than most English parish churches, its brick bell tower more barn than spire, yet the horseshoe outline of an older minaret is still visible inside the base. Mass times are posted on the door in felt-tip pen; if the bell tolls eight times while you are reading it, you have just experienced the village clock. Light sleepers should pack ear-plugs—the bell rings on the hour, every hour, night included.

Walking tracks that begin at your doorstep

Leave the square by the upper alley and you meet the GR-7 long-distance path within three minutes. Turn east along the irrigation channel and the world quietens to footfall and goat bells. The trail is level, shaded by poplars and old olives, and loops back to the village after 45 minutes—perfect jet-lag therapy after a morning flight from London City. For something steeper, continue upwards past abandoned threshing circles; after 400 m of climb the path crests a ridge giving a straight-line view south to the Mediterranean, usually a hazy silver stripe on the horizon. Winter walkers should note that morning ice lingers in the shadows; the same altitude that keeps Lobras cooler than Granada in July can mean slippery cobbles in January.

Summer hikers are better off starting at dawn. By eleven the sun is already high enough to bleach colour from the almond terraces; by mid-afternoon only the swifts move, skimming the rooftops for insects. The village fountain at the lower end of town gushes cold enough to numb your fingers—fill a bottle there before setting out, because once you leave the lanes there is no bar, no kiosk, no traffic.

Food the mules once carried

Lobras has one restaurant, one bar and no cash machine. The bar opens for breakfast at eight; order churros dipped in thick hot chocolate and you will hear more Andaluz Spanish than English in a month. Midday menus revolve around what the terraced gardens provide: migas—breadcrumbs fried with garlic, peppers and scraps of chorizo—taste better after you have seen the almond shells that fuel the fire. Evening options are limited to Hotel Huerto de Lobras, where a three-course dinner might start with beetroot salmorejo the colour of post-box paint, move on to pork cheek that collapses at the prod of a fork, and finish with lemon-olive-oil cake that convinces even fussy eaters that Spanish puddings do not have to be drenched in honey. Wine is local Granada province; ask for the envero—lighter than Rioja and half the price.

Vegetarians survive on tortilla and salads; vegans should self-cater. The tiny grocer’s opposite the church stocks tinned chickpeas, local tomatoes that still smell of leaf and, on Fridays, fresh goat cheese wrapped in brown paper. If you need oat milk or prosecco, drive back to Órgiva before 20:00 when the supermarket shutters roll down.

Seasons when the village changes shape

In late January the fiestas of San Sebastián turn the square into an open-air kitchen. Half a dozen men stir paella pans the diameter of tractor tyres while the church choir sings from the balcony. Visitors are welcome but there are no wristbands, no programme, no English commentary—just follow the smell of rabbit and rosemary. August brings the summer feria: plastic bunting, late-night flamenco streamed through speakers balanced on window-sills, and a disco that finishes promptly at 23:00 when the bar owner wants to go home. Between those two weekends Lobras reverts to a population of 149 plus whoever is staying in the half-dozen rental cottages. Spring is the kindest season: almond blossom foams over the terraces, daytime temperatures sit in the low twenties and the GR-7 smells of wild thyme crushed underfoot. Autumn means mushroom permits—ask at the town hall if you fancy foraging; without the stamped paper the Guardia Civil can fine you on the spot.

Getting here, getting out, getting cash

Fly direct to Granada from London City between June and October; the flight is two hours forty and the drive to Lobras another twenty-five. Outside those dates use Málaga, allow an extra ninety minutes on the A-92 and watch the altitude signs: sea level to 935 m in under an hour is hard on hire-car brakes. Buses from Granada terminate in Busquístar, 4 km below the village; the connecting taxi costs €12 if you can persuade the driver to make the detour. No car means no flexibility—taxi fares mount up quickly and the Sunday service does not run at all.

Parking is free but not unlimited. Spaces on the main square fill when extended families visit for Sunday lunch; latecomers squeeze onto the camino above the church and hope no one needs to get a tractor past. There is still no souvenir shop, no guided tour desk, no multilingual brown sign pointing to “Historic Centre”. That is the deal: come for the silence and you must organise your own soundtrack.

Bring euros in cash. The nearest ATM is in Cádiar, 9 km down a road that corkscrews through olive groves; the machine sometimes runs dry at weekends. Mobile data flickers—download offline maps before you leave Granada and expect to answer emails on the hotel Wi-Fi instead of beside the threshing circle.

Night skies and morning coffee

By ten o’clock the village is dark enough to see the Milky Way. Step into the lane, switch off your phone torch and let your eyes adjust: within five minutes you can distinguish the glow of Aldebaran from the navigation lights of a plane heading to North Africa. The silence is so complete that conversations carry from three houses away; couples arguing in muted Andaluz remind you that real life continues behind the white façades.

Dawn starts with the clink of milk bottles as the delivery van does its rounds, followed soon after by the first espresso machine hiss from the bar. Sit outside with a cortado and you will watch the sun lift over the ridge, lighting each terrace in turn until the whole hillside looks like a stack of pale green saucers. By eight-thirty the day’s heat is already building; by nine the first walker asks for a top-up of water and the church bell answers with nine measured strokes. Lobras does not do drama, but it keeps time better than Big Ben—and the view from the bench outside the bar beats any London skyline.