Full Article

about Alosno

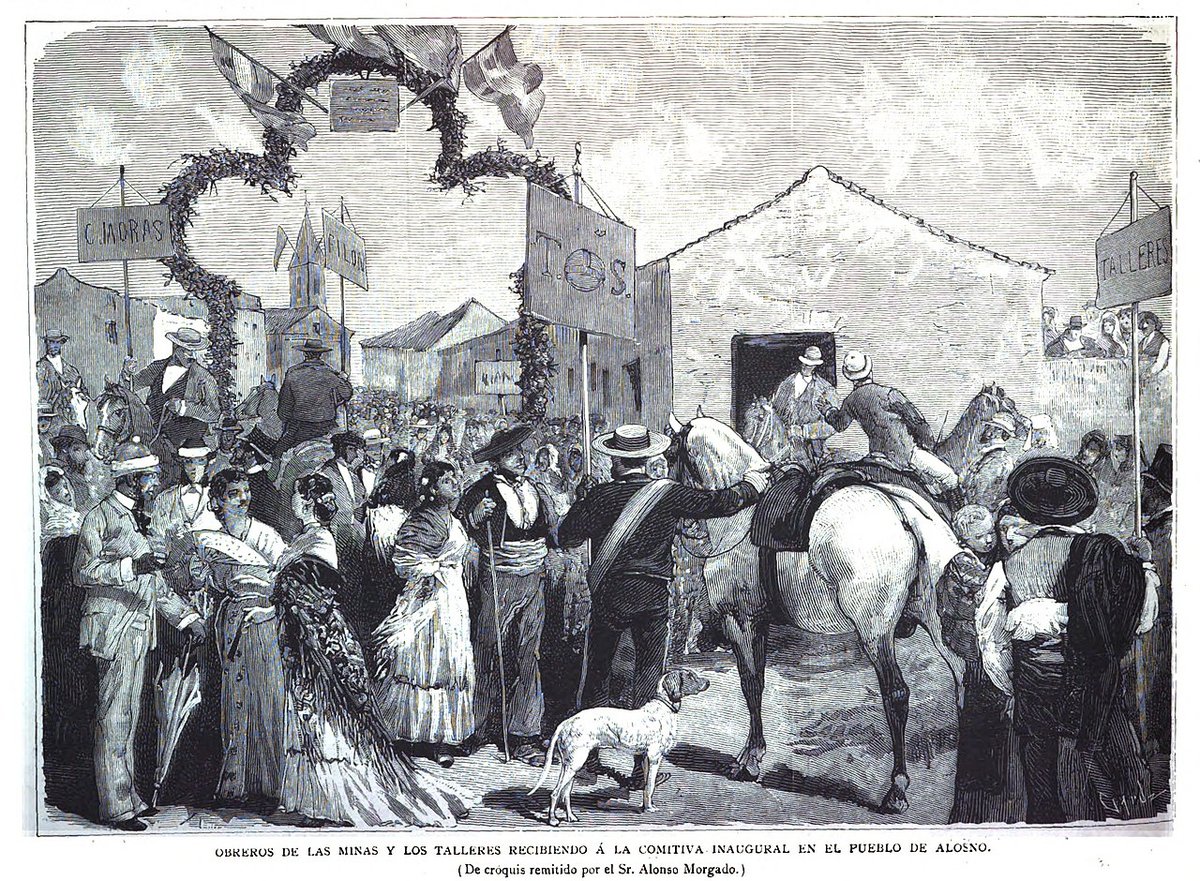

Birthplace of fandango, land of mining and cattle traditions; known for its cuisine and unique folklore echoing through every corner of its white streets.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

At 183 metres above sea level, Alosno sits neither high enough to be a mountain retreat nor low enough to feel coastal. This in-between elevation gives it a curious climate—mornings that demand a jumper even in May, afternoons that bake the limestone walls until they radiate heat long after sunset. The village straddles two worlds: the Sierra de Huelva rising behind, the marshes of the Odiel stretching ahead toward the Atlantic. It's a positioning that shaped everything here, from the copper mines that once paid for the manor houses lining Calle Real to the olive presses that still work through the night during harvest.

The Mining Museum and Other Working Relics

The Museo Minero isn't a museum in the gift-shop-and-cafe sense. It's three sheds of rusting machinery, a wall of black-and-white portraits of miners with cigarettes clamped between their teeth, and a guide—usually José from the bar next door—who'll demonstrate how the pneumatic drills worked until the last seam closed in 1992. British visitors who've made the 90-minute dash from Faro airport consistently call it "brilliant" but also "impossible to find open." The trick is to telephone the ayuntamiento at least 24 hours ahead; if no one answers, keep trying. Turning up unannounced means staring through padlocked gates while the village clocks strike three and everything shuts for siesta.

When the museum does open, it explains the village's sudden wealth in the 1950s and its equally sudden slump. The stone mansions with their broad arched doorways—built to accommodate both donkey and owner—date from this brief boom. Walk the alleys behind the church and you'll see the architectural equivalent of a confident swagger now gone quiet: wrought-iron balconies painted municipal green, coats of arms chipped by decades of rain, courtyards where a single lemon tree grows in a cracked terracotta pot.

Olive Oil, Ham and What to Actually Eat

Alosno's jamón de Alosno carries a protected designation, though the curing cellars are nothing glamorous—low white buildings on the edge of town where hind legs hang like rows of dusty violins. The flavour is milder than the more famous Jabugo version, making it a sensible starting point for British palates that find intensely acorn-sweet ham cloying. Order a plato de ibérico at Bar Central and you'll get six paper-thin slices, a basket of bread that's properly stale by Spanish standards, and a beer glass rinsed in so little water it still carries a foam collar from the previous customer.

For something less pork-heavy, try papas aliñás—cold potatoes dressed with olive oil, tuna and hard-boiled egg. It sounds like something your aunt might bring to a village fete, but the local oil carries a peppery kick that lifts it well above salad-bar fare. Vegetarians should note options are limited; even the vegetable soup usually arrives with chunks of chorizo floating like bright red lifeboats.

Walking Among Thousand-Year-Old Trees

The Ruta de los Olivares Centenarios starts opposite the cemetery on the C-431. It's not a National Trust trail—no car park, no gift shop, just a hand-painted sign and a track that disappears between silver-green hedges. Within ten minutes the traffic hum fades and you're among olive trees older than most European countries. Their trunks twist like molten wax, some split so wide you could park a Mini inside the gap. Spring brings yellow wildflowers among the roots; autumn means the whirr of tractors hauling plastic crates to the cooperative press.

The loop takes ninety minutes at English walking pace, longer if you stop to watch shearers prune branches by hand. Locals will tell you the trees produce less oil now but the flavour is deeper, something to do with roots that have tasted both drought and deluge. Whether that's horticultural fact or village pride is unclear; either way, the small bottles sold in the petrol station taste sharper and greener than anything labelled "Spanish extra virgin" in British supermarkets.

When the Bells Stop: Afternoons and Practicalities

Between 14:30 and 17:30 Alosno performs a convincing impression of a ghost town. Metal shutters clatter down, the single ATM switches to a screen wishing you "feliz descanso," even the dogs retreat into shady doorways. Plan accordingly: buy water before lunch, fill the hire-car tank, accept that you are now on rural Spanish time. Mobile coverage is patchy inside stone houses—download offline maps while you have signal on the A-49.

Evenings restart slowly. Grandmothers emerge with chairs to watch the street; bars turn televisions to the news at full volume. If you need cash for dinner, note that the nearest reliable machine is in La Redonda, six kilometres east. Most bars don't take cards, and the mining museum certainly doesn't. Budget €25–30 per head for an uncomplicated dinner of ham, local cheese and a bottle of Tierra de Barros tempranillo—cheaper than coastal prices, but not the giveaway it once was.

Fiestas and the Volume Question

Easter processions squeeze through streets barely three metres wide; drum beats bounce off stone so loudly conversation becomes impossible. The May feria in honour of the Virgin of the Asumption is gentler, more about sherry and dancing sevillanas than solemnity. British families sometimes book the village's two rural cottages for this weekend, attracted by flower-decked balconies and the promise of "authentic Spain." What the brochures don't mention is the fairground rides thumping bass until 04:00, or the fact that every teenager on a moped treats the main drag as a drag strip. Bring earplugs or join in—there is no middle ground.

Getting There, Leaving Again

Fly to Faro, hire a car, head east on the A22. After the border the road becomes the A-49; leave at exit 75, follow signs for La Palma, then HU-6101 north. The final twenty minutes twist through olive plantations and the occasional herd of black pigs grazing under holm oaks. Buses from Huelva exist but run twice daily, timed for schoolchildren rather than tourists. Without wheels you'll be stranded each afternoon, dependent on the goodwill of whoever is heading to the coast.

Drive out early enough and you can reach Faro airport for an evening flight back to Manchester or Luton, carrying a vacuum-packed ham knuckle and the smell of wood-smoke in your clothes. Alosno won't have changed in your absence; the olives will still be growing, the museum will still need that phone call, the bells will still ring on the hour. Some places promise transformation. This one simply offers a day or two of slow time—and a warning label about afternoon lockdowns British visitors ignore at their peril.