Full Article

about La Zarza-Perrunal

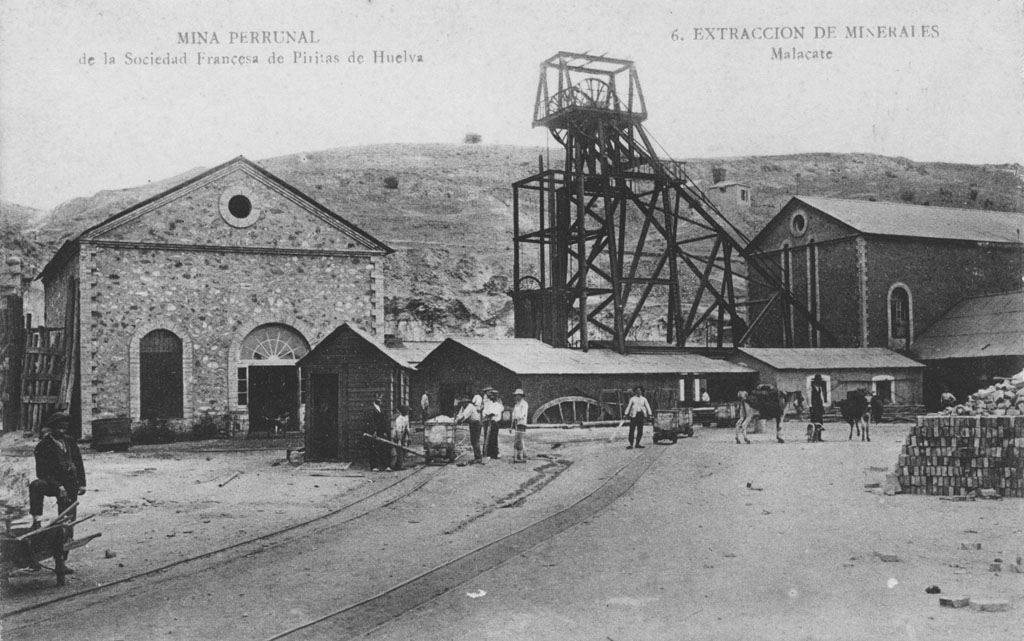

Young municipality split from Calañas with a strong mining identity; noted for its industrial heritage and the open-cast mine.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell strikes noon. Nothing happens. No tourists emerge clutching guidebooks, no tour buses clog the single main street. In La Zarza-Perrunal, midday simply means the bar owner turns up his radio slightly louder, and the elderly men playing dominoes outside don't bother looking up from their tiles. This is western Andalusia's forgotten quarter, where the Sierra de Huelva's gentle folds meet the province's mining past, and where five thousand souls have perfected the art of remaining unnoticed.

At 280 metres above sea level, the village sits in that ambiguous zone between coast and mountains. The Mediterranean lies forty-five minutes south-west, close enough for afternoon breezes to carry salt air, yet far enough that holidaymakers racing to the beach never divert from the A-49. Those who do exit at Valverde del Camino discover a landscape that refuses dramatic declarations. Holm oaks and cork trees spread across rolling hills like a well-worn carpet, their roots hiding the manganese and copper deposits that once employed half the province. The mines closed decades ago, but their ghostly infrastructure still dots the countryside—stone buildings sinking back into scrubland, their rusted machinery providing perches for hoopoes and shrikes.

The dual settlements of La Zarza and Perrunal, formally merged in 1970, maintain the suspicious politeness of cousins forced to share a house. Each preserves its own church, its own fiesta, its own fierce loyalty. Walk the three kilometres between them on the old camino real and you'll notice the subtle shifts: La Zarza's houses wear their whitewash brighter, Perrunal's doors stand fractionally wider, as if still debating who gained more from the marriage. Both, however, subscribe to the same architectural philosophy—single-storey dwellings huddled against summer heat, their walls thick enough to keep December nights tolerable without central heating.

The Church of Nuestra Señora de la Concepción squats at La Zarza's highest point, its squat bell tower more navigational aid than spiritual beacon. Built from local stone that weathers to the colour of burnt toast, it embodies the region's religious pragmatism: no Gothic fantasies here, just solid walls and a doorway wide enough for coffins and harvest floats. Inside, the air carries beeswax and centuries of incense, plus something sharper—recent plaster repairs funded by the EU, their pristine white patches marking where earthquake damage from 1969 finally got fixed. The priest, when present, doubles as the village librarian and maintains office hours that would make a French fonctionnaire blush.

Perrunal's San José church operates on even reduced hours, opening primarily for its August fiesta and whenever someone needs marrying or burying. The building's fifteenth-century foundations survive beneath eighteenth-century rebuilding beneath 1990s concrete rendering—a palimpsest of devotion and subsidence. Local legend claims the tower leans two degrees west because builders drunk on the patron saint's day laid the first stones crooked. Surveyors blame unstable mine workings. Both explanations are repeated with equal pride.

Walking these villages means surrendering to their rhythm. Streets narrow to shoulder-width between houses, then blossom into pocket-sized plazas where grandmothers establish territorial claims with plastic chairs. The Plaza de España in La Zarza functions as open-air living room, council chamber, and cricket pitch depending on hour and season. Morning belongs to mothers escorting uniformed children to the combined primary school; afternoon shifts to retired men solving Spain's economic crisis over cards; evening sees teenagers circling on bicycles, their phone screens glowing like fireflies in the dusk darkness that proper darkness becomes when streetlights switch off at midnight to save money.

The surrounding dehesa offers proper walking, though "proper" requires adjustment of British expectations. These aren't manicured National Trust paths with interpretation boards and tearooms. They're agricultural tracks used by farmers, wild boar, and the occasional Iberian lynx—though you're exponentially more likely to encounter the farmers. Routes exist more as oral tradition than mapped reality. Ask for directions to the old mine at La Joya and you'll receive enthusiastic arm-waving: past the eucalyptus plantation, left at the abandoned threshing circle, straight on until the track divides at the lightning-struck oak. GPS signals die beneath the tree canopy, forcing reliance on landmarks and common sense.

Spring transforms these walks into explosions of colour that would send Chelsea Flower Show judges into cardiac arrest. Rockroses burst white across hillsides, followed by purple phlomis and yellow broom that scent the air with coconut and honey. The brief flowering period—mid-March to early May—justifies planning visits specifically then, before temperatures climb past thirty and every piece of vegetation develops thorns or toxicity as summer defence mechanisms. Autumn brings mushroom hunting, though mycological expertise proves essential; the local hospital treats at least one overconfident visitor annually who's misidentified a death cap for something edible.

Food follows the calendar with stubborn authenticity. Winter means matanza season, when families still slaughter their own pigs and spend subsequent weeks converting every gram into edible preservation. Visit in January and bar counters display wheels of chorizo drying like artisanal light fittings, their paprika-red skins contrasting with white mantles of mould that get wiped off before eating. The resulting platters arrive without garnish or ceremony—thick slices of morcilla that bleed onion and cinnamon, lomo cured until it resembles burgundy leather, fat white beans stewed with pig's ear and enough garlic to repel vampires across two counties.

Summer shifts to gazpacho and migas, the latter a dish that began as shepherd's sustenance and evolved into culinary religion. Breadcrumbs, not the packaged sort but yesterday's bread grated into rough rubble, get fried in olive oil with garlic and whatever the garden provides—green peppers, grapes, melon if someone's feeling fancy. Proper migas requires constant stirring for forty minutes, a task that doubles as arm exercise and social event. The bar owner cooks them outdoors over wood fire every Sunday, charging €6 for portions that would feed a family of four elsewhere.

Accommodation options reflect the village's ambivalence towards tourism. One casa rural occupies a renovated farmhouse outside Perrunal—thick walls, beamed ceilings, swimming pool that gets cleaned when the owner remembers. Three double rooms, no children under ten, breakfast featuring eggs from chickens you can hear conducting dawn chorus. Booking requires telephoning Maria José directly; she doesn't do online reservations because "the internet is for watching videos of cats." Alternative arrangements involve staying in Valverde del Camino's Hotel Andévalo, twenty minutes drive away, where rooms face an interior courtyard designed to confuse guests into thinking they're somewhere more interesting.

Reaching La Zarza-Perrunal demands commitment that separates genuine travellers from tick-box tourists. From Seville airport, the journey involves motorway to Huelva, then secondary roads that shrink progressively until meeting the HU-4102, a strip of tarmac barely wider than British country lanes. The final approach passes through eucalyptus plantations that smell like cough drops and dehesas where black pigs root beneath oak trees, their future as jamón ibérico assured if they avoid speeding cars. Public transport exists in theory—a twice-daily bus from Huelva that sometimes arrives, sometimes doesn't, depending on whether the driver's mother needs collecting from the doctor.

What you won't find matters as much as what exists. No souvenir shops flamenco-ing for business. No restaurants offering "authentic" tapas at London prices. No boutique hotels with rooftop pools and yoga at dawn. The village offers instead something increasingly precious—Spain's rural reality, unfiltered and unpolished, where lunch takes three hours because that's how long lunch takes, where teenagers still dream of escaping to Madrid, where British expats haven't discovered property bargains. Yet.

Visit in December for the fiestas patronales and you'll witness devotion that makes British village fetes resemble corporate team-building. Processions wind through streets barely wide enough for the Virgin's platform, brass bands playing marchas that sound like circus music played by people who've never seen circuses. Fireworks explode at intervals throughout the night, terrifying dogs and ensuring nobody sleeps properly for a week. The local council provides free wine from plastic barrels, a gesture of municipal generosity that would trigger health-and-safety meltdowns back home.

Or come in late October when the chestnut harvest begins, though "harvest" overstates organised agriculture. These are wild trees whose nuts get collected by villagers wearing gloves against the spiky casings, then roasted over drums cut from washing machines and sold in paper cones for €2. The smell—wood smoke and caramelising starch—drifts through streets already scented with woodsmoke from heating fires lit against the evening chill. Temperatures drop surprisingly sharp at this altitude; mornings bring mist that pools in valleys like milk spilled across green velvet.

Leave before Sunday lunch extends into siesta, before the bar radio switches from local news to football, before you start recognising faces and they begin acknowledging yours with the slight nod that means you've been temporarily accepted. La Zarza-Perrunal doesn't need saving, discovering, or promoting. It needs what it's always needed—people willing to accept life at Spanish rural speed, where nothing happens slowly, and where tomorrow arrives precisely when it should, GPS signals or otherwise.