Full Article

about Colmenar

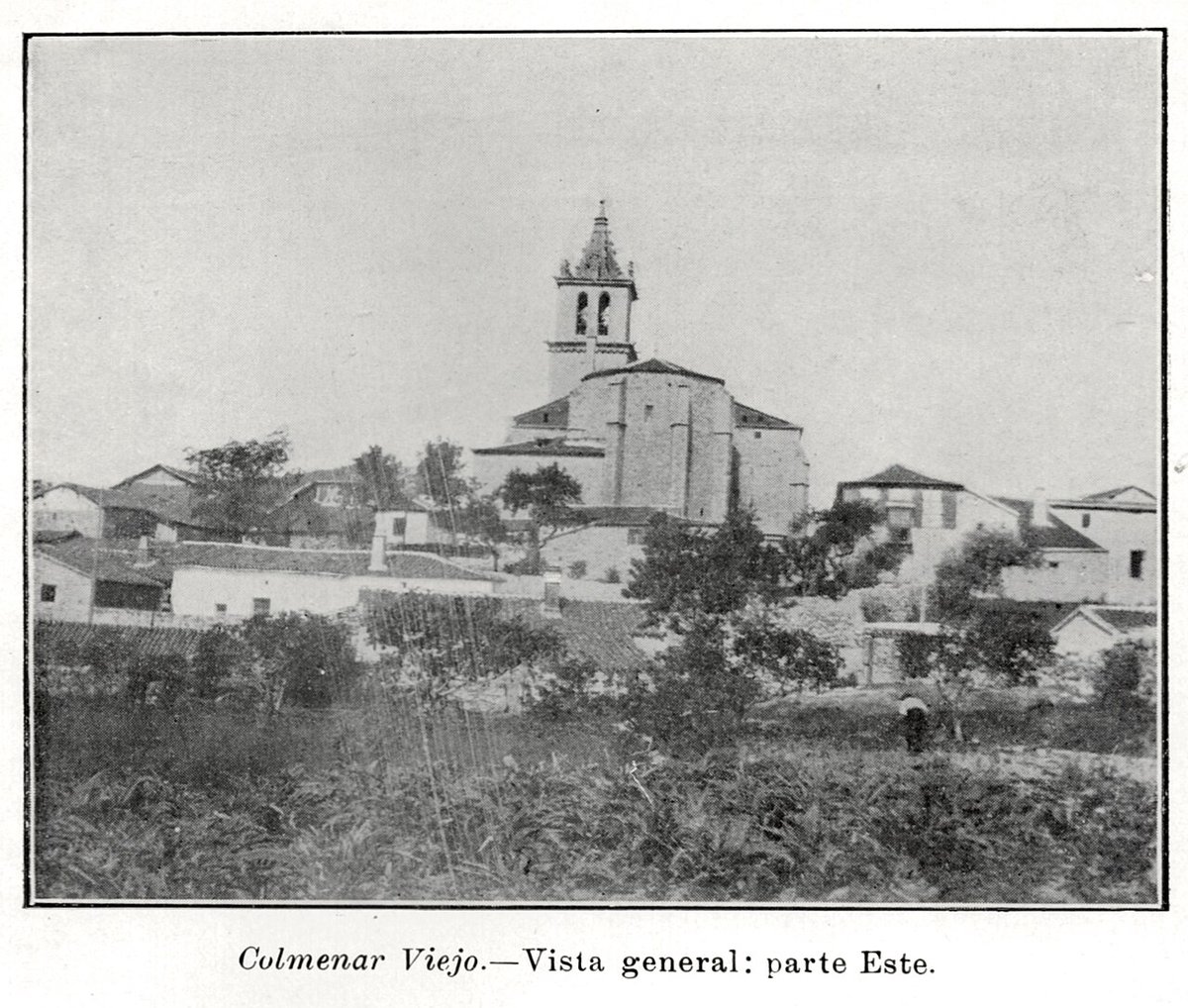

Capital of the Montes de Málaga, known for its honey and cured meats, set in mid-mountain country of holm oaks and olives.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The 07:15 bus from Málaga drops you beside a cement works. No archway of orange blossoms, no geranium-draped balconies—just the smell of diesel and a gradient that makes calves burn before you've found breakfast. This is Colmenar, administrative capital of the Axarquía region, 700 m up the northern flank of the Sierra de Alhama. It is white, yes, but in the same way a council block is white: whitewash over concrete, painted quickly before the heat arrives.

A place that keeps the lights on for itself

Three and a half thousand people live here year-round, enough to support a chemist, a vet, two small supermarkets and a Friday market where the loudest stall sells horse collars. The bakery opens at six; by half past, farmers are drinking brandy-and-coffee at the bar, discussing olive-oil prices in machine-gun Spanish. Tourists are noticed because they are unusual, not because anyone is waiting to fleece them. If you want flamenco tablaos or pottery souvenirs, drive twenty minutes to Comares—Colmenar has council offices instead.

The village’s one postcard moment is accidental: stand at the top of Calle Carrera at 17:00 and the December sun fires the brick-coloured earth so hard the valley looks like a kiln. Ten minutes later the light has gone, the temperature has dropped eight degrees and women in housecoats are shouting children indoors. Instagram is not invited.

What passes for sights

The sixteenth-century Iglesia de la Asunción squats on the main plaza like a bulldog in a frock. Its square tower, built by Moorish masons who stayed after the Reconquista, leans slightly north—an quirk you only spot if you lean the same way after too much sweet Malaga wine. Inside, the Baroque retablos are heavy with gold leaf that looks sprayed from a can; the caretaker will switch on the lights for a euro, then follow you in case you pocket the seventeenth-century Virgin. The effect is more neighbourhood watch than spiritual awakening.

Behind the church, a lane barely two metres wide corkscrews up to the Ermita de San Isidro. The walk takes fifteen minutes and passes six front doors, three tethered dogs and one smell of frying garlic that will haunt you till lunch. The chapel is locked except on 15 May, when the entire village processes here, blesses the fields and eats free migas flavoured with orange peel and chorizo fat. Arrive the day before and you’ll find only swallows nesting in the bell tower and a man selling chilled lager from a cool box—payment by honesty box, 1.50 € a can.

Walking tracks that punish the over-confident

Colmenar sits on the southern edge of the Sierras de Tejeda, Almijara y Alhama natural park: serious limestone country. The tourist office—one room inside the town hall, open Tuesday and Thursday mornings—will hand you a photocopied map of the Ruta de los Olivos Milenarios. The trail heads west along a stone drovers’ road first laid by the Romans, then improved by every generation until it became a concrete tractor path. After 4 km the tarmac runs out and you are among thousand-year-old olives whose trunks resemble melted candle wax. The going looks gentle; it is not. Between tree terraces the path drops 200 m in a kilometre, then climbs the same on loose shale. In April the temperature can swing from 6 °C at 08:00 to 24 °C by noon; carry both fleece and two litres of water or turn back when the first fingertip goes tingly.

Harder still is the full Sierra de Alhama traverse, 17 km east–west along a knife-edge ridge. The trailhead starts 6 km above the village at Puerto de los Alamos, reachable only by your own car—no taxi will wait. Fog can roll in from the Mediterranean thirty kilometres away and reduce visibility to ten metres even in July. Every year someone from Seville in beachwear has to be carried out by Guardia Civil helicopter; don’t add to the statistic.

Food the way the school kitchen makes it

There are no boutique gastrobars, only family-run ventas that open when the owners feel like it. The safest bet is the cafeteria inside the CEIP Andalucía primary school, open to the public from 07:00 till 14:00. Ismail, the caretaker-cook, serves coffee strong enough to etch chrome and tostadas rubbed with tomato and a splash of olive oil from the cooperative down the road. A breakfast of two tostadas, café con leche and fresh orange juice costs 2.80 €; you’ll share Formica tables with fourteen-year-olds in football kit. Menu del día appears at 12:30: expect gazpachuelo (a thick fish-and-potato soup thickened with mayonnaise), followed by goat stew so tender it falls off the bone when you look at it. Pudding is a rosco de vino, a doughnut ring flavoured with aniseed and sweet wine; drink black coffee or the combination tastes like Christmas in a prison cell.

Outside term time the place shuts, so phone the ayuntamiento first. If the gates are locked, drive three kilometres south on the MA-3102 to Venta Los Prados, a truckers’ bar with wild-boar stew and fluorescent lighting. They close on Tuesdays, randomly.

Seasons: when to come and when to stay away

March brings almond blossom snow across the lower slopes and daytime highs of 18 °C—perfect walking weather before the flies wake up. May smells of fennel and wild thyme; the night-time temperature hovers around 12 °C, so you will still need a jumper even when the sunburn on the back of your neck says midsummer.

July and August are brutal. The village itself sits just above the heat trap, but at 14:00 the streets are an oven. Only mad dogs and English teachers on TEFL placements venture out. Accommodation without air-conditioning is unsleepable; there is none with it, so day-trip instead, arriving at dawn and leaving before the melt begins.

November is the quiet month. Bars play the radio at conversational volume, old men argue over dominoes and the first rains turn the earth to slick red clay. Bring waterproof boots; the limestone absorbs water like a sponge and paths become skating rinks. On the upside, wild mushrooms appear—ask permission before foraging on private land or you’ll meet a shotgun.

Practicalities without the brochure speak

Getting here: Málaga airport to Colmenar is 48 km, mostly motorway. Hire a car—public transport exists but the weekday bus leaves the capital at 15:00 and returns at 06:30 next morning, timings that assume you have family to visit rather than sights to tick. Petrol stations on the A-45 close overnight; fill up before the mountain stretch.

Sleeping: There are no hotels. The nearest beds are in casas rurals scattered on olive farms 5–10 km outside the village; expect stone cottages, wood-burning stoves and owners who speak only Spanish. Weekend rates start around 70 € a night for two, drop to 45 € mid-week in January. Book through the provincial tourist board website or prepare for lengthy WhatsApp negotiations involving badly translated voice messages.

Money: The single ATM belongs to Unicaja and sometimes runs out of cash on Sunday evening when the weekenders depart. Bring euros or pay by card in the supermarkets; most bars still prefer cash.

Language: English is rarely heard. A smile and “Buenos días” get you further than any app, especially when ordering beer: “Un corto” earns a 100 ml glass, “un doble” doubles the measure and the price (1.20 € / 2.40 €).

The honest verdict

Colmenar will not seduce you at first sight. It is scruffy, uphill and short on fairy-tale corners. Stay a little longer, though, and its virtues emerge: walks that empty your head faster than therapy, oil that tastes of green tomatoes and pepper, evenings so silent you can hear moth wings beat. Come for the trails, the cheap set-menu lunch and a glimpse of inland Spain before Instagram finds it. Leave before you start expecting fireworks—this village saves its sparks for the people who live here, and that is exactly the point.