Full Article

about Albuñol

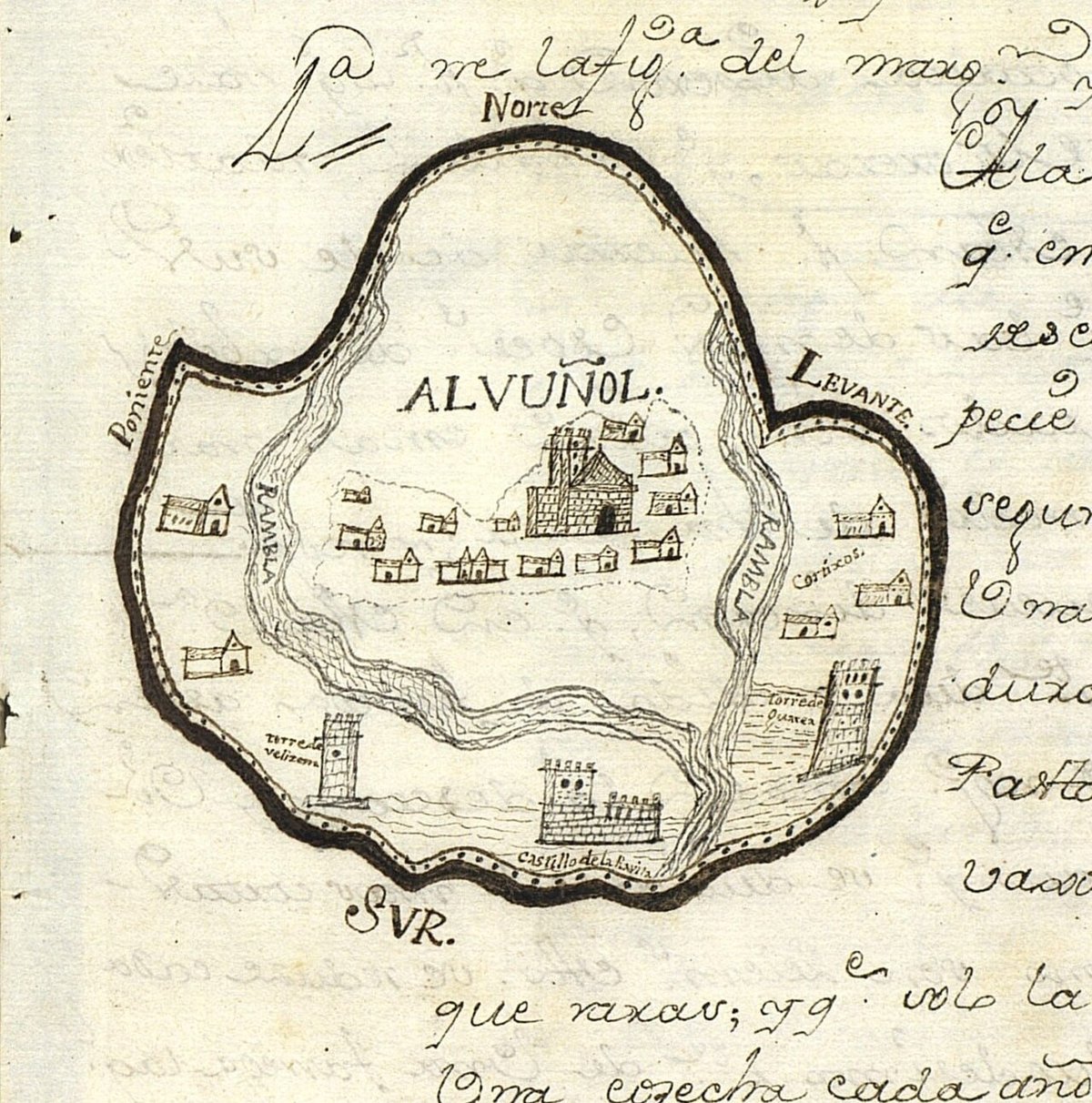

A coastal municipality that blends beach and low hills; known for intensive farming and quiet beaches like La Rábita.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church belltower of La Encarnación rises above a patchwork of plastic sheeting. From the café terrace on Plaza de la Constitución, you can trace the lines of polytunnels that spill down the valley towards the Mediterranean, eight kilometres away. This is Albunol's daily paradox: a mountain village whose economy depends on the sea-level crops growing beneath the white tents.

At 260 metres above sea level, the village proper sits where the Sierra de Lujar begins its climb towards the Alpujarra. The air carries a mix of mountain clarity and agricultural industry. Morning coffee arrives with the sound of tractors heading to the invernaderos, where farmers tend subtropical crops that shouldn't logically grow in Europe. Custard apples, avocados and mangoes thrive here thanks to the microclimate created by the mountains' protection against northern winds.

The old town climbs uphill from the church, its narrow streets designed for donkeys rather than the small cars that now squeeze between whitewashed walls. Flowerpots spill geraniums from wrought-iron balconies. Elderly men in flat caps occupy benches beneath orange trees, discussing the day's business in rapid Andalusian Spanish that even fluent visitors struggle to follow. The Thursday market transforms the main street into a social hub where gossip flows as freely as the cheap local wine sold from plastic containers.

Balanegra, the coastal appendage, feels like a different world. Here, dark volcanic sand meets fishing boats pulled up on the beach. The houses stand practically on the shoreline, their walls salt-stained from winter storms. In the beachfront bars, fishermen repair nets while discussing the day's catch over small beers. The menu changes with the season: sardines threaded onto cane skewers and grilled over driftwood fires, tiny squid flash-fried with lemon, fish soup that tastes of the Atlantic despite the Mediterranean location.

The relationship between village and coast defines daily rhythm. Morning sees an exodus of workers down the winding road to the greenhouses. Evening brings them back uphill, dust-covered and ready for the social ritual of tapeo. The bars around Plaza de Abastos fill gradually. First come the agricultural workers, still in their field clothes. Later, families with children, then the elderly who eat fashionably late by British standards but early by Spanish ones.

Walking options radiate from the village like spokes. The Contraviesa range rises behind, its slopes terraced with ancient almond groves and newer vineyards producing the local muscatel. Spring walking brings clouds of blossom and the scent of wild herbs underfoot. Autumn offers grape harvest and the chance to buy wine directly from small producers whose bodegas occupy caves carved into the hillsides. Summer hikes require early starts; by eleven the heat becomes oppressive, sending sensible walkers back to village bars for ice-cold beer and tortilla.

The coast provides alternative routes. A coastal path connects Albunol's beaches, passing through small coves where snorkelling reveals surprisingly clear water when conditions allow. Winter storms can deposit vast amounts of plastic debris, agricultural detritus from the greenhouses that proves the connection between mountain agriculture and marine environment. Local volunteers organise regular clean-ups, but the problem persists, an uncomfortable reminder of the area's primary industry.

Cultural life follows the agricultural calendar. February's San Blas fiesta features the traditional blessing of throats, elderly villagers queueing outside the church for protection against winter ailments. Easter processions wind through streets barely wide enough for the carved religious statues, their bearers practising year-round for the privilege of carrying centuries-old figures. August's Virgen del Mar celebration sees the village's patroness loaded onto a fishing boat for a maritime procession, fireworks exploding over the water at midnight.

The British residents who've made Albunol home appreciate its authenticity. "It's not pretty-pretty," explains one long-term expat in the butchers, "but it's real. The baker knows how I like my bread. The mayor drinks in the same bar as the tomato pickers." Integration requires effort; few locals speak English, and attempts at Spanish are met with patient encouragement rather than frustration. The Thursday market becomes a language school where pointing and smiling overcome grammatical inadequacies.

Practical considerations shape the experience. A hire car transforms access possibilities; without one, you're dependent on irregular buses that operate on Spanish timekeeping. The drive to Malaga airport takes ninety minutes through dramatic mountain scenery, though fog in winter can close the coastal route. Granada's smaller airport lies closer but offers fewer flights. Accommodation mixes village houses, often with roof terraces catching mountain breezes, and coastal apartments where air conditioning becomes essential during July and August nights that barely drop below 24 degrees.

The village supports basic needs: small supermarkets, a pharmacy, medical centre, even an English-speaking doctor two days weekly. Larger shopping requires trips to Motril or Almeria, both twenty-five minutes away. Evening entertainment centres on people-watching rather than organised activities. British visitors sometimes struggle with this; those expecting karaoke bars or expat pubs find instead conversations about irrigation problems and tomato prices.

Albunol works best for travellers seeking Spain rather than Spain-themed entertainment. The beaches remain largely Spanish-dominated, crowded at weekends with families from Granada escaping inland heat. August brings a minor invasion from Madrid and Barcelona, but nothing approaching the Costa del Sol saturation. Prices reflect local wages rather than tourist premiums; a three-course menu del dia costs twelve euros, wine included.

The greenhouse landscape that initially shocks gradually reveals its logic. These plastic seas fund the village's survival, allowing young people to remain rather than migrating to cities. The environmental cost sits uncomfortably beside economic necessity, a modern dilemma played out beneath mountain slopes where traditional agriculture continues alongside industrial-scale production.

Come prepared for contradictions. This is a working village that happens to have beaches, not a resort with local colour. The mountains provide spectacular backdrops but also trap summer heat. The agricultural prosperity funds services but changes landscapes. Albunol offers an unvarnished version of contemporary Spanish village life, rewarding those who value authenticity over aesthetics, conversation over entertainment, and the gradual accumulation of small daily pleasures over Instagram moments.