Full Article

about Vilches

Town ringed by reservoirs with a castle on the hilltop; sweeping views.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The morning bus from Jaén deposits just three passengers outside Bar California. One is a local farmer carrying a new chain-saw blade, another a British couple who've overshot their intended stop by twenty kilometres. Their mistake is instructive: Vilches doesn't announce itself. The village simply materialises after thirty minutes of olive trees, a compact grid of stone houses and orange-blossomed streets at 548 metres above sea-level, where the Sierra Morena begins its rolling descent towards the Guadalquivir valley.

The Arithmetic of Olives

Work it out and each resident commands roughly 150 trees. They spread in every direction, their silver-green canopies stitched together by dry-stone walls and dirt tracks that double as walking paths. This isn't scenery; it's an agricultural ledger written in vegetation. The hills rise and fall like gentle breathing, soft enough for an easy bike ride yet sufficiently varied to keep things interesting. Come May, the fields throw up poppies and wild marjoram between the trunks, and the air carries the peppery scent of new oil from the cooperative mill on the edge of town.

Inside the village, the arithmetic shifts. Five thousand souls share three squares, two bakeries, one small supermarket and a handful of bars where breakfast costs €2.20 if you stand at the counter. Houses are built from the same limestone that pokes through the soil, their roofs tiled in weathered terracotta. Nothing is postcard-pretty; instead everything looks lived-in and slightly stubborn, much like the elderly men who occupy the benches outside the church each evening, caps pulled low against a sun that still feels fierce at seven o'clock.

What the Castle Saw

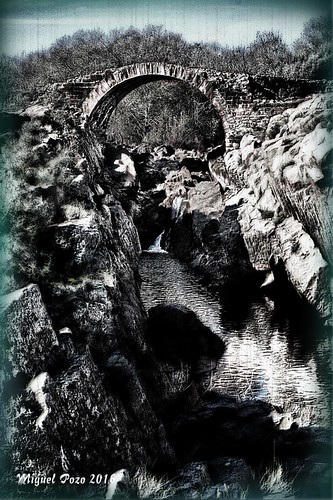

Three kilometres north, the Castillo de Giribaile keeps watch from a crag that suddenly breaks the olive monotony. Only fragments remain – a curtain wall, the base of a keep, foundations so thoroughly scavenged that locals once used them as field boundaries. Yet the position explains the view: a 360-degree sweep across the province's most lucrative crop. Drive up before nine (the track is rough but passable in a normal hire car) and you'll share the ruins with perhaps a pair of booted Germans and a Spanish family who've brought tortilla wrapped in foil. By eleven the stone radiates heat like a storage heater; sensible people retreat to the village for coffee.

The castle's real value lies in orientation. From here you can trace the old mule path that once linked Vilches to the kingdom of Castile, spot the cortijo where bulls are raised for corridas, and work out why the village grew where it did: close enough to water, high enough to see trouble coming, surrounded by land that repaid effort with oil.

Eating What the Fields Provide

Lunch starts at two sharp. In Casa Marchena, secrero ibérico arrives sizzling on a clay dish, the pork streaked with fat that tastes faintly of acorns and smoke. Ajo blanco follows – chilled almond soup sharpened with garlic and served with moscatel grapes. It's dairy-free, filling and costs €6, though the owner won't make a fuss about allergens; ask once and she remembers. The house wine comes in a plain glass bottle, light enough to drink like Beaujolais, strong enough to make the cycle back to your accommodation feel adventurous.

Evening options are limited. One British visitor described the nightlife as "a bottle of local red on the terrace or bed at ten", which sums it up. If you're staying at family-run cortijo El Añadio, Ramona needs breakfast-time notice to fire up the olive-wood grill. Dinner might be wild boar stew or simply migas – fried breadcrumbs laced with chorizo – but it will be generous and accompanied by stories of how her grandfather bought the farm with post-civil-war wages earned rebuilding railways.

When to Come, How to Leave

Public transport exists on paper. A bus leaves Jaén at 07:15, another returns at 19:30. Miss it and you're looking at a €35 taxi to Linares-Baeza station, thirty minutes away on the Córdoba–Almería line. Car hire is simpler: Vilches sits five minutes off the A-4 autovía, exactly halfway between Madrid and the Costa Tropical. Petrol is cheaper at the village cooperative than on the motorway, and the staff will check your oil unasked.

April and late-October deliver 22 °C days cool enough for walking, warm enough to sit outside at night. August climbs past 38 °C; even the flies move slowly. Accommodation is thin: one three-room guesthouse above the bakery, two rural cortijos within a ten-minute drive, prices from €55 a night including breakfast. Book ahead during olive-harvest weekends in November, when Madrid families return to help and every spare bed is claimed.

The Useful Misunderstanding

Back at Bar California, the British couple realise their error and consult their phone. The barman, who speaks no English, draws them a map showing where they meant to go and where they now are. He adds a circle around Vilches, then a larger one taking in the castle, the bull farm, the oil mill. They order another coffee, studying the diagram. By the time they leave, the woman has typed "worth the detour" into her notes, though she'll struggle to explain why when friends ask later.

Perhaps it's the ratio again: 150 trees per person, three squares, one castle, enough. Vilches offers no spectacle, just the slow revelation of how thoroughly a place can be shaped by what grows around it. Stay a night, maybe two. Walk the olive lanes at dawn when the trunks glow pink, eat what the fields provide, listen to the evening quiet that starts at nine-thirty sharp. Then drive on, aware that you've glimpsed the working interior most travellers thunder past at 120 km/h, heading somewhere they believe matters more.