Full Article

about Alcalá de Guadaíra

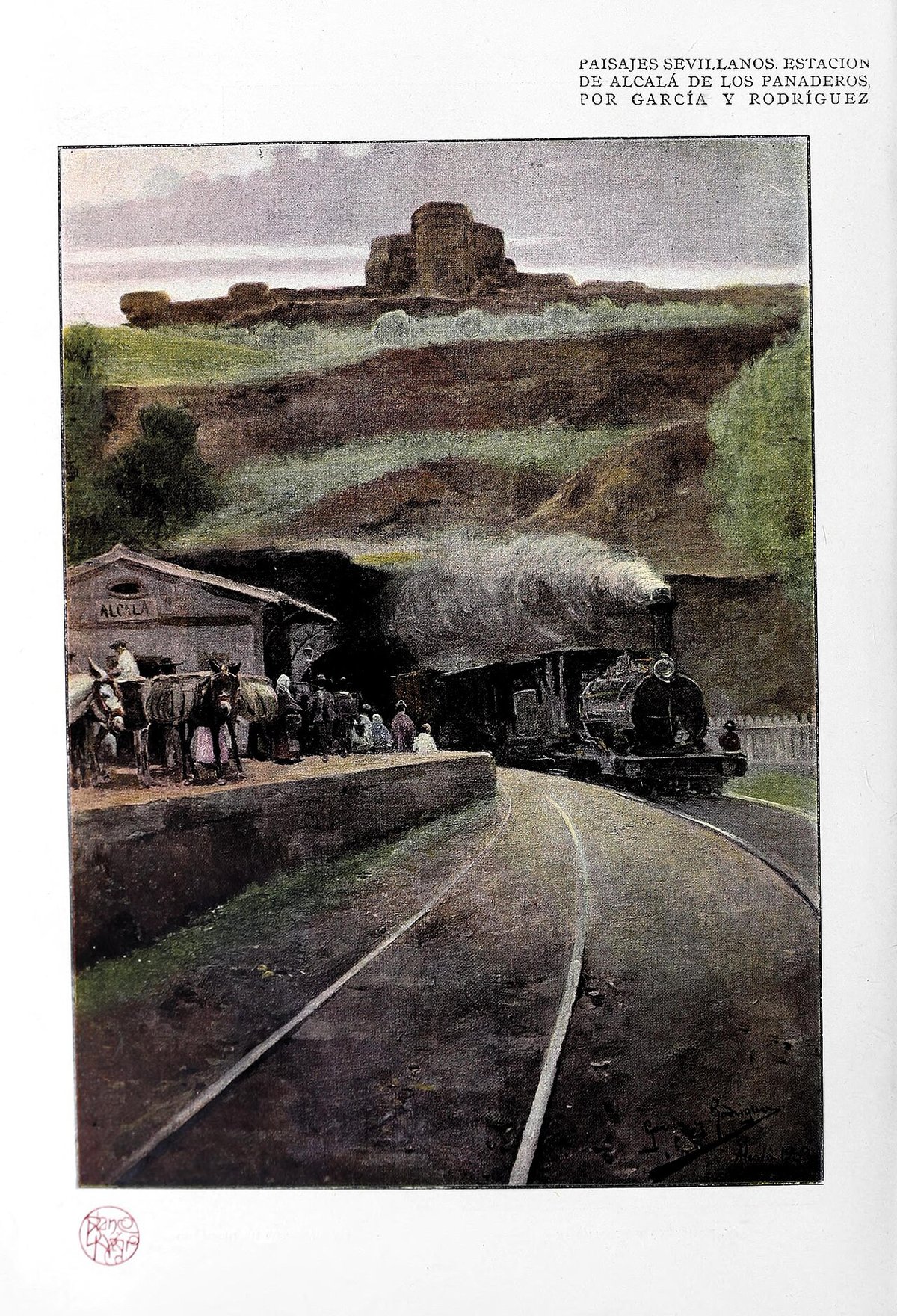

Known as the city of bakers, it stands out for its imposing Almohad castle and the Guadaíra riverside natural park.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The first clue is the smell. Long before the castle appears on its ridge, the car window frames a warm, yeasty draught that drifts across the A-92 at kilometre 16. It is 07:30 and Alcalá’s 11 official bakeries are tipping the night’s loaves on to wooden racks. One of them, Horno San Bartolomé, has been doing this since 1820; the present baker’s great-grandfather fired the same stone floor that now browns today’s pan de Alcalá – a crusty, slightly chewy white loaf that once fed Seville when the capital’s own ovens couldn’t keep up.

Seville airport sits only 22 km west, yet almost every visitor races straight past the turn-off. The result is a working town of 76,000 where the tourist count is still measured in dozens, not coachloads. That makes Alcalá useful: a place to stretch your legs, fill your lungs with bread vapour and be back in Seville for dinner, or, if the flight is late, a last-minute lunch five minutes from the departure gate.

The ridge, the river and the flour

The town owes its existence to topography. The Guadaíra river slices a shallow gorge through the soft Los Alcores limestone, creating a natural defensive platform on the north bank. The Almohads exploited it in the 12th century, throwing up an eleven-tower fortress whose walls still throw long shadows over the modern grid of orange-lined avenues. Entry is €3, or free on Tuesday afternoons, but timing matters: the gates shut from 14:00 to 16:00, a siesta so strictly observed that even the resident storks relocate to the shade.

Below the castle the river bends lazily south, fringed by a six-kilometre belt of poplars and eucalyptus that locals call the Parque de los Molinos. The name is literal: twelve stone watermills, some dating from Moorish times, once ground the wheat that Seville imported because its own flat land was too valuable for housing. Most wheels are gone, yet the channelled race water still gurgles under footbridges, and kingfishers use the broken sluices as diving boards. A flat, 45-minute circuit links the best-preserved mills – Realaje and Benarosa – with picnic tables and a small bird-hide overlooking a reed bed busy in April with purple herons and the occasional glossy ibis.

Cyclists can extend the outing by following the Ruta Verde south-east towards Mairena del Alcor; the surface is rolled limestone dust, manageable on a hybrid, but check the weather: after heavy rain the path turns to ochre porridge and you’ll push rather than pedal.

A breadcrumb trail for breakfast

Serious eating starts early. By 08:00 the tahonas on Calle Ancha are stacking roscos – soft, sweet bread rings – next to tortas de aceite flavoured with sesame and aniseed. The easiest introduction is to buy a 90-cent mollete (oval breakfast roll), have it split and drizzled with local olive oil, then lean against the counter with the pensioners who treat the bakery as their morning salon. If you prefer a chair, Pastelería Centenaria, two streets south, occupies a 1910 townhouse with pressed-tin ceilings and marble tables; coffee is decent and the almond suspiros arrive still warm.

Convento de Santa Clara, a cloistered order founded in 1528, sells biscuits via a wooden turntable set into the wall: point at the box of corazones de almendra, place cash on the lazy-Susan, rotate, and the sweets reappear with the change. The nuns keep no regular timetable; if the grille is shuttered, ring the bell politely and wait.

Lunch is less traditional. La Cueva de la Zarzamora, opened by two Sevillian brothers in a converted water cistern, serves only puddings and cocktails. The menu changes weekly, but expect gin topped with popping candy, torrija ice-cream made from yesterday’s pan de Alcalá, and a sharing plate called Mala Suerte that arrives under a glass dome of candy-floss smoke. It is open Thursday to Sunday, no bookings; add your name to the clipboard by the door and expect a 20-minute queue after 13:30.

Getting there, getting round, getting stuck (briefly)

Alcalá is not on Seville’s metro map; the quickest route is to pick up a hire car at the airport, follow the A-92 east for 17 km and leave at junction 16. Free parking lies under the railway bridge (Puente del Tren de los Panaderos) on the southern ring road; from here it is a ten-minute riverside stroll to the mills and twenty uphill minutes to the castle. A taxi from the airport rank costs a fixed €35 – worth it if your flight home is mid-afternoon and you want to compress a morning’s sightseeing.

Public transport exists but tests the patience. The M-170 bus leaves Seville’s Plaza de Armas hourly, takes 40 minutes and drops you on Avenida de Andalucía, a 1 km walk from the old centre. Sunday services shrink to every two hours, so check the return timetable before you set off or you’ll spend an unintended afternoon in a café whose only other customer is the baker on his break.

When to come, and when not to

April and October give daytime temperatures in the low twenties – ideal for the castle climb – and river foliage at its greenest. July and August are fierce: thermometers touch 40 °C by 11:00, the castle closes early and even the bread smell wilts. Winter is mild but can be damp; the mills’ paths turn slick and the Guadaíra swells enough to drown the lower picnic benches. If you do visit between December and February, bring shoes with grip and expect the bakeries to push roscos de reyes, the sugar-encrusted epiphany rings that Spaniards hide figurines inside.

Crowds are rarely a problem except during the Cabalgata de Reyes (5 January evening) when 30,000 locals line the avenue for a three-hour parade of floats chucking 8 tonnes of sweets. Book accommodation only if you enjoy dodging flying polvorones.

Exit via the sauce

Time your departure for mid-afternoon and you can still squeeze in the flour museum (Harinera), a converted mill whose 19th-century French turbines look steampunk enough for a film set. English tours exist but must be requested a day ahead; ring +34 955 880 990. The gift shop sells 1 kg sacks of stone-ground flour should you fancy baking your own pan de Alcalá back home – declare it, mind, or the bread aroma that began the day may end with a customs queue at Gatwick.

Then it is back along the A-92, bread on the passenger seat, castle shrinking in the rear-view mirror, and the realisation that Seville’s suburbs can still keep a secret.