Full Article

about Palos de la Frontera

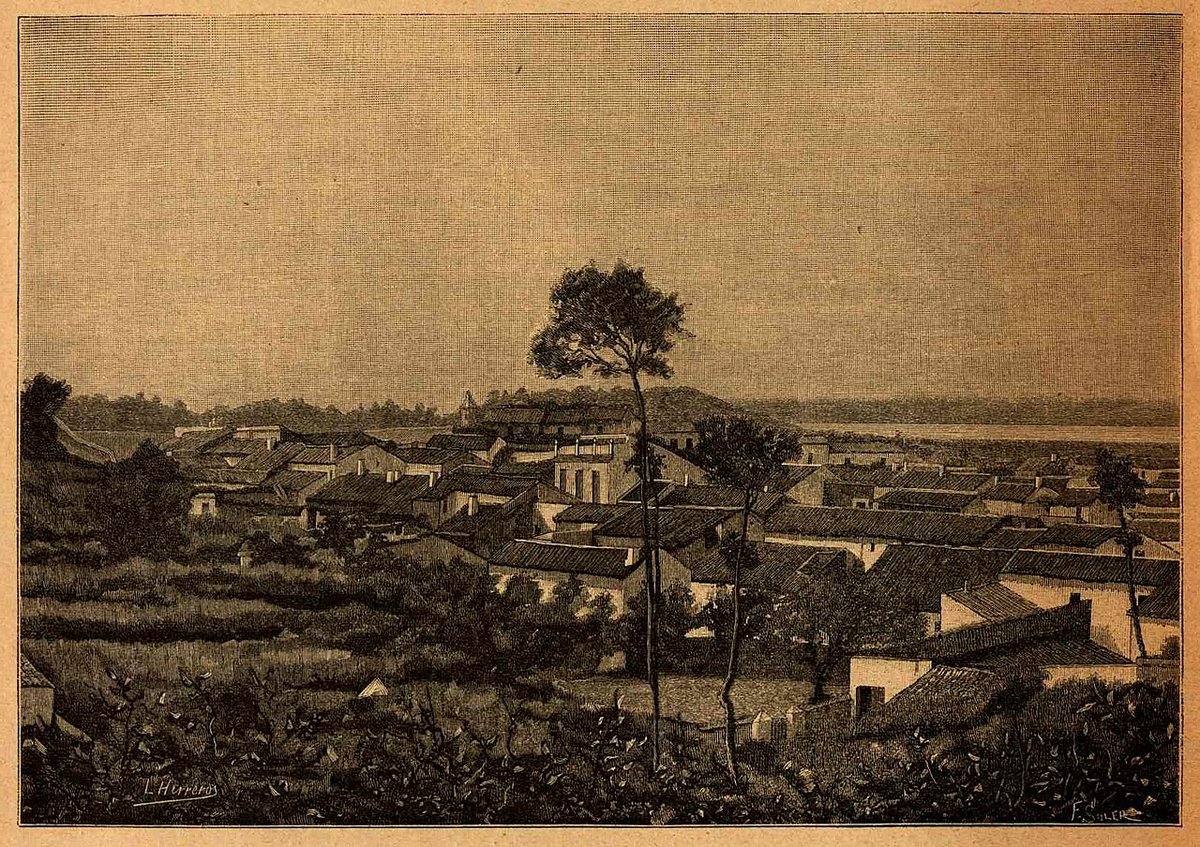

Cradle of the Discovery of America, from where the caravels set sail; key historic site with the Monasterio de La Rábida and the Muelle de las Carabelas.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

Salt, Mud and a Borrowed Boat

Walk to the end of the wooden pier at first light and the Rio Tinto looks like liquid rust. The colour comes from iron washed out of the nearby mines, but locals still joke that the river remembers the blood of empire. Three caravels bobbed here one summer morning in 1492, waiting for a tide high enough to carry them west. The town that supplied the ships has barely climbed above sea level since—23 m at its highest—and the smell of diesel and drying nets still drifts through streets named after the men who left.

Palos de la Frontera keeps its history low-key. There is no triumphant statue at the quayside, only a modest plaque recording that Martín Alonso Pinzón, captain of the Pinta, once lived two minutes’ walk away. School parties march past it without stopping; the teacher is usually more interested in herding them towards the monastery bakery for €1.20 olive-oil biscuits.

The Friars Who Bank-Rolled an Ocean

Santa María de La Rábida squats on a hillock ten minutes from the river. The 13th-century Franciscan convent is small, biscuit-coloured and easy to miss if you follow a sat-nav that still calls the road “Calle de la Fontanilla”. Inside, the Mudéjar arches are painted the same green you will later see on fishing boats—an accidental echo that makes the monks feel like honorary skippers. A single panel explains, in English, how fray Antonio de Marchena smoothed Columbus’s route to the royal court; the rest of the labels are Spanish only, so borrow an audio-guide at the desk before the queue forms. They run out by 11 a.m. most Saturdays.

Entry is €5 and the ticket now includes a timed slot in the new interpretation gallery. Here, alongside astrolabes and worm-eaten logs, a wall text admits that the expedition opened “a catastrophic chapter for Indigenous peoples”. British visitors tend to linger longest over this section; it is still rare in Andalucía to find such frank museum prose.

From the cloister you can look down the reed-fringed channel where the caravels were careened. The tide no longer reaches the monastery—silt and strawberry farms upstream have seen to that—but on a windy day the Atlantic still tastes close.

Scale Models That Make You Whisper

Downriver, the Muelle de las Carabelles houses full-size replicas of the Niña, Pinta and Santa María. British TripAdvisor regulars call the stop “the best €4 we spent in Huelva province” and they are right. You board by a swaying gangplank, bang your head on a beam, then realise the entire crew of 40 slept on deck. Children instinctively lower their voices; even teenagers forget to pose for selfies when they see the size of the hold that once carried live pigs and a year’s biscuit.

Interpretation is again patchy—Spanish-only panels pinned to masts—but a free translation app does the trick. Allow 45 minutes, longer if the attendant starts demonstrating 15th-century knots. The adjoining botanic garden, planted with species the sailors brought back (sunflowers, prickly pear), is a useful shady circuit when the thermometer edges past 35 °C.

Lunch Before the Coach Parties Arrive

Palos eats early by British standards. By 1.30 p.m. the bars along Calle Martín Alonso Pinzón are already on second sitting. Locals order coquinas—tiny clams steamed with bay and lemon—then mop the liquor with bread that tastes of wood smoke. If shellfish feel risky, El Bodegón grills pork presa over holm-oak and the menu has photographs for easy pointing. House red comes chilled whether you ask or not; at €2.20 a glass no one argues.

Coach groups from Seville start rolling in around 11 a.m. and empty the kitchens by 3 p.m. Time your visit either side and you will share the dining room with beret-wearing grandfathers arguing about Sunday football.

Marshes That Glow at Dusk

North of town, the Tinto spills into a maze of salt flats and pine rimmed boardwalks. The Marismas del Tinto trail is signed from the N-442 roundabout; ignore the half-built golf resort on your left—bankruptcy froze it in 2009—and head for the single-track road that smells of eucalyptus. Park where the tarmac ends (free, no facilities) and follow the raised path for 3 km. Spoonbills and avocets feed in summer; in October hundreds of flamingos practise formation flights that look suspiciously like an RAF display.

Evening light turns the water copper, then rose. Bring insect repellent; the same wetlands that attract birds also breed enthusiastic mosquitoes. The loop takes an hour at bird-watcher speed, fifteen minutes if you march, but you will probably stop just to listen: traffic noise disappears and the only engine is the occasional fishing skiff humming down the main channel.

A Beach Detour if You Have Wheels

Mazagón’s wide Atlantic beach lies 12 km south-west, a fifteen-minute drive on the A-494. Pine-backed dunes give way to firm sand that feels Cornish at low tide and Portuguese when the surf picks up. Spanish families set up for the day with cool boxes and footballs; British visitors usually plant wind-breaks outside the El Timón beach bar and order cañas of Alhambra until the sun drops. Parking is free among the trees; showers cost 50 cents and work only in high season.

Getting There Without the Car

Public transport exists but demands patience. The M-403 bus leaves Huelva’s Estación de Damas roughly every 45 minutes; journey time is 25 minutes and a single costs €1.55. Last return departs at 20:30, so a day trip is feasible only if you are happy with a 6 a.m. start from Seville. Taxis back to Huelva run about €20 after 9 p.m.; Uber barely operates this far west. Hire cars start at £28 a day from Huelva rail station and make combining Palos, La Rábida and Mazagón straightforward.

What the Town Does Not Tell You

Palos is proud of its Columbus pedigree, yet it is still a working fishing port. That means diesel lorries rattling past the Casa Museo de Martín Alonso Pinzón and gulls fighting over yesterday’s catch on the pavement. The museum itself opens only when the single attendant returns from coffee; hours posted on the door are decorative. If it is shut, peer through the window—the ground-floor recreation of a 1490s kitchen is visible and free.

Monday morning is best avoided: both monastery and wharf shut, and half the cafés pull down their shutters for staff day-off. Rainy days turn the mudflats into a brown mirror but also flood the riverside path; wellies are wiser than walking boots.

Should You Stay the Night?

Accommodation within the town limits amounts to two guesthouses and a motel aimed at truckers. Most visitors base themselves in Huelva (20 min by car) or combine Palos with an overnight in Moguer, where boutique convent conversions offer rooftop pools and jamón-scented breakfasts. Palos itself winds down by 10 p.m.; the only late action is the bar at the marina where fishermen play dominoes and refuse to translate the TV debate.

Come back at dawn, though, and you will see the same ritual that happened 530 years ago: boats edging down the channel, engines muttering, white decks striped by the rising sun. The river still carries them, the Atlantic still waits, and the town that once lent its boats to history goes on mending nets as if the world had never changed.