Full Article

about Linares de la Sierra

A small village tucked in a valley, preserving the purest mountain architecture; known for its artistic stone-paved house entrances.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The first thing that strikes you is the sound of water. Even before the white houses come into view, a stream rattles through the valley, turning old stone washing tanks where women once scrubbed sheets. At 505 m above sea-level, Linares de la Sierra is high enough for the air to feel rinsed, yet low enough for holm oaks and cork trees to hold their green all year. The village—barely 300 residents—spills down a fold in the Sierra de Aracena, 85 km north-west of Seville, and the road in is a slow-motion switchback that finally spits you onto the HU-8105 bypass. Park here; the lanes below are barely shoulder-wide and the locals have little patience for three-point turns.

Morning mist and mossy stones

Dawn is the optimum moment. At 08:00 the chestnut woods opposite the church still exhale threads of mist, and the cobbles—polished to a marble slick by centuries of hooves and tractor tyres—glisten without yet being treacherous. Winter visitors learn to read the darker stones: those are the "green carpets" of moss that can send an unwary boot skating. Summers are kinder, but even then the streets funnel heat upwards; sensible walkers adopt the Spanish rhythm—out early, siesta, back out at dusk.

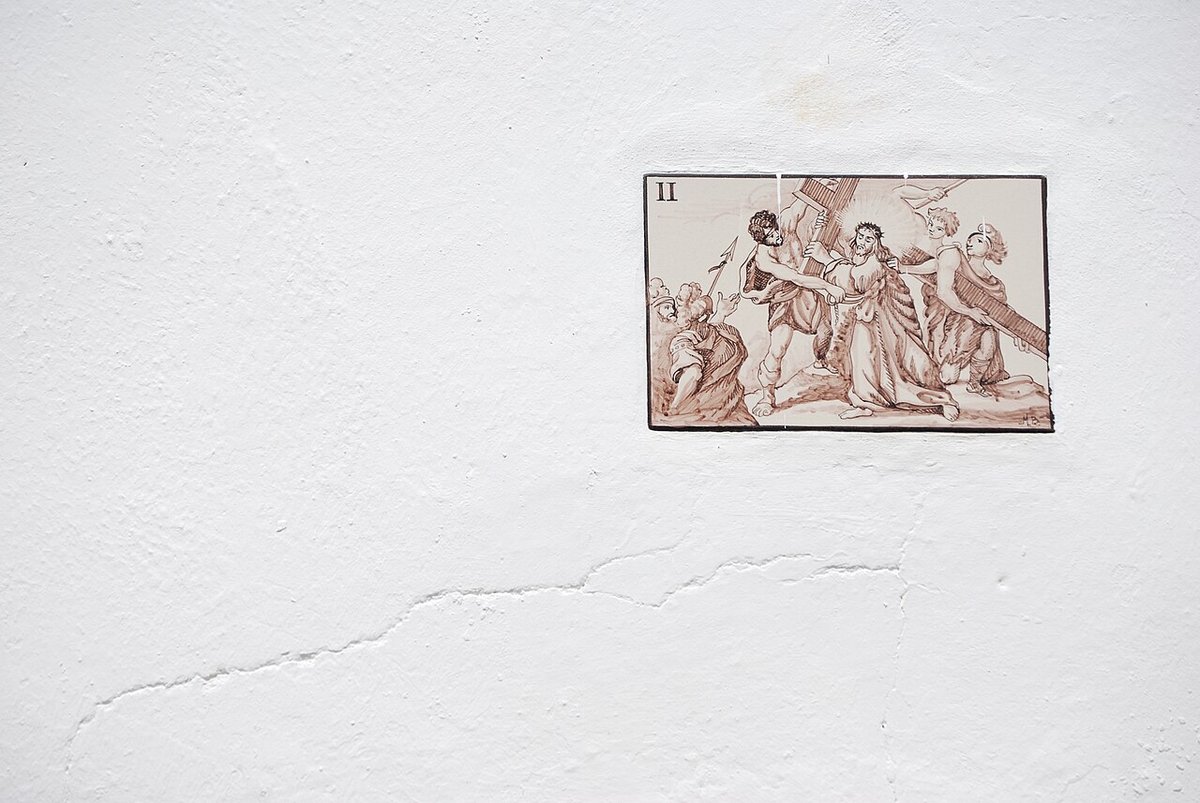

No map is required. From the small stone fountain at the top of the village, every calle eventually funnels into Plaza de San Juan. The eighteenth-century church squats here like a referee, its bell tolling the quarter-hour with no regard for holiday lie-ins. Step inside if the door is ajar: gilt is kept to a minimum, the timber roof smells of incense and candle wax, and the temperature drops five degrees in as many paces.

Ham, honey and a Michelin surprise

Food is inseparable from altitude. Up here the black-footed pigs roam the dehesa, hoovering acorns whose oleic acid seeps into the flesh and later into your breakfast toast. The butcher on Calle Real will slice jamón ibérico to order, paper-thin and still room-temperature; ask for 50 g and he’ll weigh it on scales older than the crown on a five-peso coin. Round the corner, the Friday bakery van sells piñonate, a brittle disc of honey and pine nuts that snaps like Florentine toffee—buy a whole one (€8) and the vendor will tuck it in tissue as if it were bone china.

The real shock is Restaurante Arrieros, a former muleteers’ bar now sporting a Michelin mention. Inside, beams are blackened by time rather than interior design, yet the tasting menu leaps from rosemary-smoked presa (the pig’s hidden shoulder steak) to quince-stuffed figatellos. Brits accustomed to set-lunch bargains should brace themselves: dinner runs to €45, bookings by WhatsApp only, and it shuts without apology on Monday and Tuesday outside July–August. No one apologises; demand outstrips the twelve tables.

Paths where donkeys still commute

Linares is a launch pad rather than a cul-de-sac. A signed 6-km loop drops from the lower fountain, crosses the stream and climbs through sweet-chestnut coppice to the abandoned hamlet of El Cabezo. Goats stare, donkeys carry firewood, and the only traffic jam is a flock of sheep rounded up by a dog called Lola. The gradient is gentle—this is not the Lake District—but the return gives thighs a pleasing ache that justifies an extra slice of torta at tea-time.

Serious walkers can stitch together day-long traverses to Alájar or Aracena, both worth an overnight if you fancy bagging two villages. Whichever route you choose, carry water; fountains marked “agua potable” are safe, but many dry up in late summer. Mobile signal is patchy once you drop into the valley—download an offline map before leaving the bar’s Wi-Fi.

When the village throws a party

Three Kings on 5 January turns the streets into an open-air nativity. Bonfires crackle, someone hauls a loudspeaker onto a balcony, and children in tinsel wings process behind Gaspar, Balthazar and a very tired-looking Melchior. The population swells five-fold with Spanish day-trippers, yet foreign faces remain rare. If you crave quiet, come the week after; if you want atmosphere, reserve early—Aracena’s guesthouses fill first, Linares’ single three-room hostal second.

Late June brings the patronal fiesta for San Juan Bautista: brass bands, pig on a spit, and dancing that continues until the church bell chimes four. August’s Virgen de los Ángeles is smaller, aimed at locals home from Seville. Both fiestas are free to watch, though you’ll be expected to buy raffle tickets for the paella—€2 funds next year’s fireworks.

Practicalities the brochures miss

Cash is king. The last ATM stands 12 km away in Aracena; the village shop will not accept cards for a packet of crisps. English is thin on the ground—learn “¿Hay sitio para cenar?” (“Is there space for dinner?”) and you’ll dine; without it, you may be waved away kindly. Accommodation is limited: Hostal Linares has clean rooms from €45, breakfast €5 extra, but there is no receptionist after 21:00. Most visitors base themselves in Aracena and drive up for the day; the road is twisty but perfectly paved—count 25 minutes from the A-66 junction.

Weather can flip. At 500 m, Linares escapes the frying-pan heat of Seville, yet snow is not unknown in February. Spring brings wild asparagus along the verges; autumn smells of damp leaves and mushroom hum. If it rains, cobbles darken to gunmetal and the uphill hike from the car park becomes a low-level assault course—stick to the stone gutters for grip.

Leaving without the gift-shop moment

There is no souvenir stall, no fridge magnet of a dancing pig. What you take away is respiratory: wood smoke in your coat, the faint sweetness of azufaifo (wild jujube) on your fingers, the memory of a village where life is still measured in bread deliveries and the price of cork. Linares will not keep you busy for a week; it will, however, reset your internal clock to something approaching human pace. Drive back down the HU-8105, windows open, and the descent feels like re-entering a faster, coarser film. The antidote is simple: turn the car round, order another café sombra—half coffee, half milk—and let the bell of San Juan mark time for a little longer.