Full Article

about Cazorla

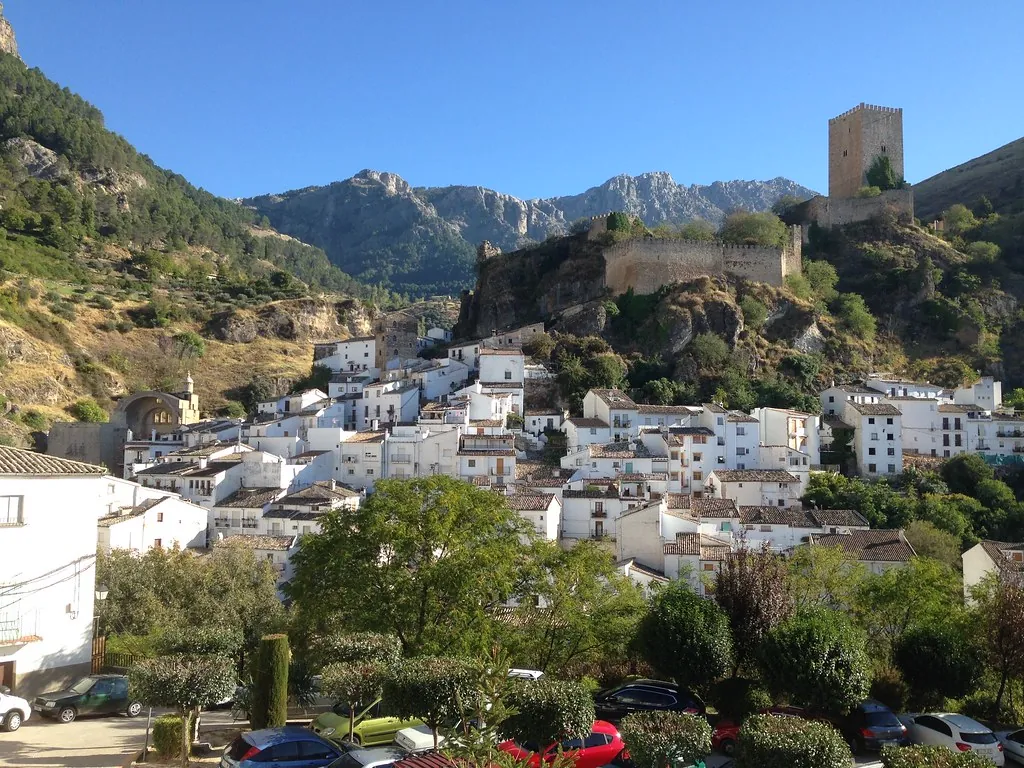

Tourist capital of the sierra; picturesque town with a castle and main gateway to the Natural Park

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The road from Úbeda climbs steadily for forty-five kilometres, each hairpin bend revealing another layer of olive trees until, quite suddenly, the sea of silver-green gives way to limestone cliffs and the temperature drops five degrees. At 826 metres above sea level, Cazorla appears almost unexpectedly—a white tumble of houses clinging to the mountainside, its streets steep enough to make even fit walkers pause for breath.

This isn't one of Andalucía's polished tourist towns. The cobbles are uneven, the gradients unforgiving, and the locals still look surprised to hear English spoken in the tapas bars. Yet that's precisely what brings increasing numbers of British visitors willing to swap beach towels for walking boots. Cazorla functions as the gateway to Spain's largest protected area, the Sierras de Cazorla, Segura y Las Villas Natural Park, where golden eagles soar above forests of Aleppo pine and wild boar root through undergrowth that bursts with violet-scented rosemary.

The Upper Town and Its Shadows

Start at the top—always the best policy in mountain towns. The ruins of Castillo de la Yedra stand sentinel over Cazorla, their weathered stones testament to centuries of strategic importance. Moorish foundations support later Christian additions, though what remains is more atmospheric than intact. The climb rewards with views across terracotta roofs to the olive plains beyond, a patchwork stretching towards the distant Guadalquivir valley. Even in July, when the coast swelters, afternoon winds whip across this exposed ridge. Carry a jumper.

Below the castle, the Renaissance church of Santa María squats between rock and river, its Plateresque façade surprisingly elaborate for such a remote spot. The adjacent Plaza de la Corredera serves as the town's practical heart—cashpoint, pharmacy, and the bar where elderly men argue over dominoes at eleven each morning. This is where you'll discover tapas still arrive free with every drink, a Spanish tradition that's disappeared from most coastal resorts. Try the local morcilla—blood pudding spiced with onions and rice, richer than British black pudding but equally satisfying on cooler evenings.

Walking Into Wild Spain

Cazorla's real appeal lies beyond its streets. The Rio Borosa trail follows a medieval watercourse through narrowing gorges, past abandoned mills where stone wheels lie moss-covered among wild garlic. The full route to Valdeazores lagoon demands six hours and decent fitness levels, though shorter circuits reward casual walkers with waterfalls and crystalline pools perfect for overheated feet. Spring brings botanical theatre—violet-scented blooms unique to these mountains carpet the lower slopes, while griffon vultures circle overhead on thermals rising from sun-warmed rock.

For gentler exploration, the village-to-village route connecting Cazorla with La Iruela offers spectacular scenery without excessive effort. La Iruela's own castle perches on a crag like something from a western film set, its restored tower accessible for a small fee. The two-kilometre walk between settlements passes through olive groves where farmers still harvest by hand, beating branches with long canes until fruit rains onto nets spread below. November's harvest brings the air alive with the scent of crushed olives—sharp, green, intoxicating.

Mountain Kitchens and Market Days

Food here reflects altitude and history—hearty sustenance for shepherds and hunters rather than the seafood-leaning cuisine of coastal Andalucía. Gachas, a thick porridge of flour, paprika and wild mushrooms, appears on winter menus alongside trout from the Guadalquivir's headwaters. The local olive oil carries Denominación de Origen status, its peppery bite perfect for drizzling over toasted bread rubbed with tomato and garlic. Even dessert stays local—almond cakes sweetened with rosemary honey produced by mountain apiaries where bees feast on aromatic herbs.

Saturday's market fills Plaza de Santa María with colour and noise. Stallholders shout prices in rapid Spanish—€3 for a kilo of wild asparagus, €8 for a small wheel of goat's cheese wrapped in chestnut leaves. The cheese tastes of thyme and sunshine, softening to spreadable consistency as the day warms. Arrive early; by noon most produce has sold to local housewives who've shopped here for forty years and know exactly which vendor offers the best morcilla or sweetest oranges.

Practical Realities

Cazorla demands a car. Public transport exists—a daily bus from Jaén, another from Granada—but schedules favour locals over tourists and finish early. Hire at the airport and accept that the final forty-five kilometres take ninety minutes on winding mountain roads where guardia civil vehicles hide behind bends, speed cameras at the ready. Fill up before leaving the A-road; petrol stations inside the park are rarer than golden eagles.

Accommodation ranges from functional hostels at €35 per night to converted manor houses charging €120 for rooms with four-poster beds and mountain views. Many British visitors base themselves in the newer part of town where streets widen enough for parking, walking ten minutes uphill to reach historic centre restaurants. Book ahead for Easter week and August fiestas—Cazorla swells with returning emigrants, hotel rooms disappearing months in advance.

Monday closures catch many visitors out. The tourist office shutters, most museums lock doors, even some bars remain dark. Plan trekking routes for Mondays instead, when trails empty and wildlife sightings increase. Carry cash—mountain ATMs run dry at weekends when city escapees arrive, and rural bars won't break notes for coffee. Download offline maps before arrival; phone signal dies within minutes of leaving town.

Evenings cool dramatically year-round. That 30-degree afternoon can drop to 15 by sunset, mountain air draining heat as quickly as it arrived. Pack layers regardless of season, and don't assume summer means sandals—these cobbles have been polished by centuries of feet and become treacherous when wet. Winter brings occasional snow, closing higher trails and transforming Cazorla into something approaching a Pyrenean village. Access improves from March onwards, though April showers can arrive with dramatic intensity, turning mountain paths into streams within minutes.

The Honest Verdict

Cazorla won't suit everyone. Those seeking flamenco shows and beach cocktails should stay on the coast. The streets are steep, the entertainment low-key, English spoken sparingly. Yet for walkers, bird-watchers, or anyone wanting to experience Andalucía before tourism smoothed its rougher edges, this mountain town delivers authenticity in spades. Come prepared for early nights, substantial meals, and the kind of silence that makes city dwellers initially uneasy. Within forty-eight hours, that same silence becomes addictive—the sound of Spain as it existed long before budget airlines and holiday packages discovered the coast below.