Full Article

about Palma del Río

Orange-growing town at the confluence of the Genil and Guadalquivir rivers, ringed by an Almohad wall and birthplace of celebrated matadors.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The 08:43 to Seville is already warm when it slides out of Palma del Río station, and the air on the platform smells faintly of soap. That scent is the first clue: thousands of orange trees surround the town, and for four weeks in late March their blossom turns every breeze into cheap perfume. Walk the lanes inside the twelfth-century walls at seven in the morning and the fragrance is almost dizzying—no guidebook mention required, just follow your nose.

Palma isn’t a show-stopper; it’s a working market town of 21,000 that happens to have kept its Moorish outline. Most visitors pass through on the way between Seville and Córdoba, notice the neat river path, the low white houses and the castle that isn’t really there, and decide to stay for lunch. The clever ones book a night, because the place makes sense after the day-trippers have gone and the temperature drops enough to think straight.

What the walls once kept out

Start at the old gate, Puerta de Sevilla, where the road still narrows to single-file and delivery vans fold in their mirrors like nervous cats. The Almohad walls are stubby—two metres thick in places—but they wrap the historic core in a continuous loop you can walk in twenty minutes. From the top of the surviving tower you look south across the Vega del Guadalquivir, a pancake-flat quilt of allotments and orange groves that disappears into heat haze. Northwards the view is rooftops and church towers, the Renaissance bell-tower of La Asunción poking up like a after-thought.

The church itself sits on the bones of the main mosque: you step through a Gothic portal into a nave that still smells of incense and floor wax. Inside, the Baroque retablo glitters with gilt so fresh it could have been finished last week; in fact it was 1692. There’s no admission charge, but a discreet box hopes for two euros towards roof repairs. Drop it in—the tiles lift like ship planking whenever the Levante wind blows.

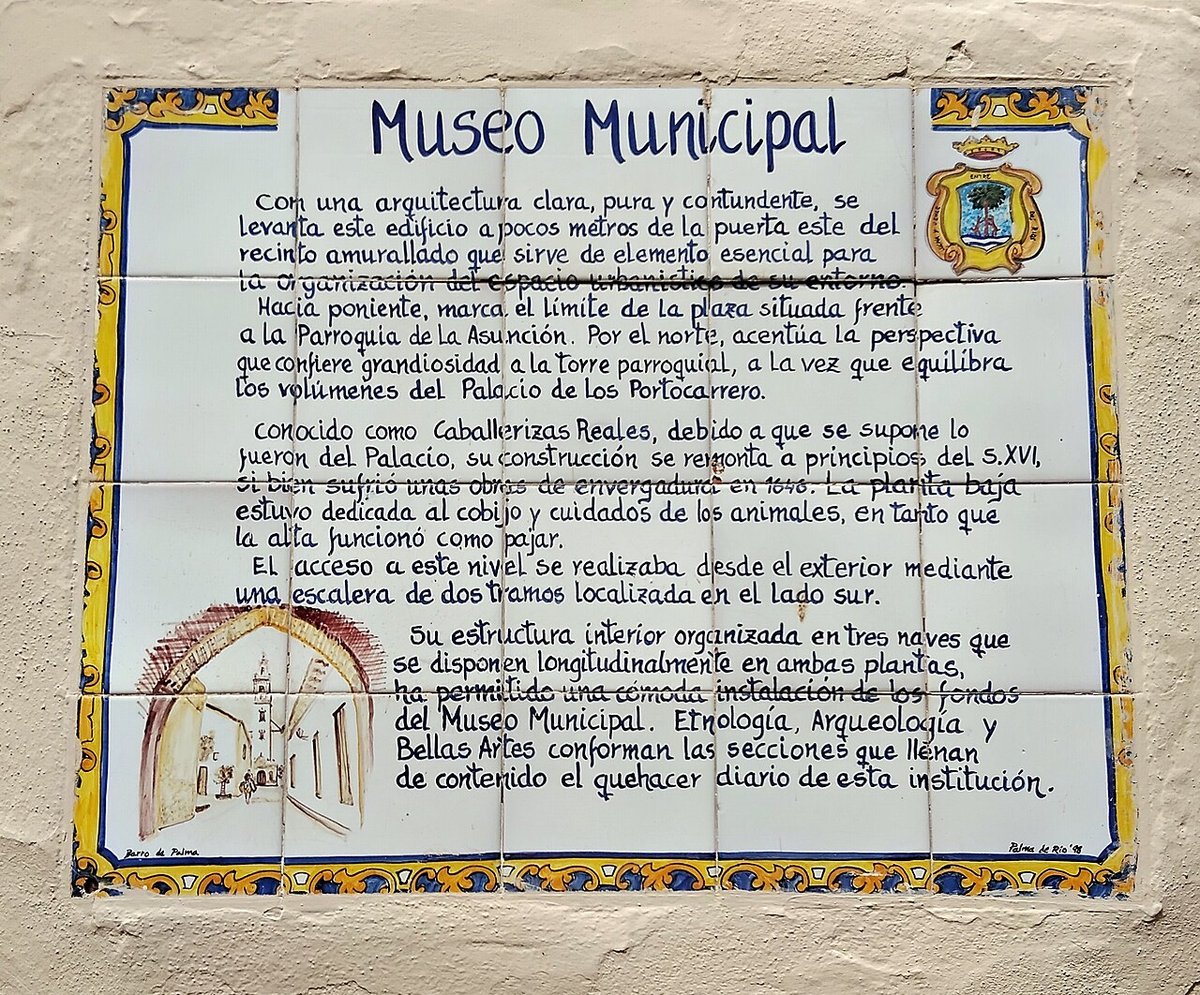

Round the corner, the Convento de San Francisco has been turned into the town museum. It’s small, air-conditioned, and mercifully quiet after midday. One room is given over to agricultural gadgets: wooden olive crushers, brass irrigation locks, a hand-forged grafting knife sharp enough to make a surgeon jealous. Another displays fragments of Roman pottery dredged from the river—proof that people have been growing things here for rather a long time.

River life, flat and slow

The Guadalquivir is only 200 m wide at this point, coffee-brown and lazy. A paved path—the Pasarela—runs downstream for 3 km through poplars and reeds. Evening is the sensible time; cyclists in hi-vis vests whizz past, but walkers have the edge. You’ll see herons, the occasional turtle sliding off a log, and old men casting plastic chairs into the water to test the depth before settling with a can of beer. Swimming isn’t encouraged—currents can shift after winter floods—but the council has installed a pontoon where teenagers practise inelegant dives while their mothers pretend not to watch.

If you need a longer stretch, rent a bike from the kiosk by the indoor market (€12 a day, helmets optional but advised; Spanish drivers treat cyclists as mobile chicane). Head upstream towards Almodóvar and you’ll pass wooden barges tied to rusted rings, still used to ferry oranges across to the cooperative at harvest. The scent changes from blossom to damp earth and back again as irrigation channels switch on and off with metronomic precision.

What to eat when the mercury climbs

Palma’s restaurants assume you’re either a picker on a 15-minute break or a family that hasn’t eaten since breakfast. Portions are large, prices low, and anything ‘a la naranja’ is likely to be local. At Casa Paco on Calle San Francisco the orange salad arrives as a wheel of sliced fruit topped with salt cod, black olives and enough raw onion to frighten vampires. It shouldn’t work, yet the combination is oddly refreshing, especially with a chilled glass of the local dessert wine—thick as marmalade, served in a miniature tumbler.

Meat eaters gravitate towards rabo de toro, bull’s-tail stew reduced until the sauce resembles molten liquorice. Half-ration (media ración) feeds two if you order bread. Vegetarians do better at lunchtime, when most bars offer a pisto—Spanish ratatouille—topped with egg. Don’t expect hip alternatives; almond milk hasn’t made it this far inland.

Churros are a breakfast ritual. Cafetería California opens at 06:30 and the first batch is usually gone by seven; pensioners mop up chocolate with the dedication of people who remember real rationing. If you’re catching the early train, phone the night before and they’ll bag yours to go.

Beds behind cloisters

Accommodation is limited and none of it is grand. The standout is the Hospedería Convento de Santa Clara, a fifteenth-century nunnery turned three-star hotel. Bedrooms open onto a cloister where swallows nest in the eaves; the Wi-Fi struggles with stone walls two metres thick, but that’s what data-roaming is for. Doubles start at €65 including a breakfast of toast dripped with local olive oil so green it looks radioactive. Park outside—the gate arch was built when cars were still imaginary.

Cheaper options cluster round the main square: Hotel Castillo is clean, modern and mis-named (the castle remains are 300 m away), but rooms at the back overlook allotments where cockerels provide a free alarm clock. Ask for a fourth-floor balcony; you’ll see the river glinting between rooftops and the first blossom catching streetlight at dawn.

When to come, when to leave

Late March to mid-April is the sweet spot: blossom, 24 °C afternoons, and the fierce Levante wind hasn’t yet started to nag. May adds wildflowers along the river but also the Romería, when half the town camps outside the city and loudspeakers blast flamenco until the small hours. Book early or stay away.

Summer is brutal. Temperatures touch 40 °C by eleven in the morning; shutters close, streets empty, and the only movement is the ice-cream freezer humming in the supermarket. Many restaurants shut for the entire month—owners head to the coast where margins are higher and air-conditioning standard. If you must come, schedule museum visits before 11:00, then retreat to the darkest bar you can find for a caña and whatever football replay is on television.

Winter is mild—think Bournemouth in late October—but the river path can flood after heavy rain, and the blossom is six months away. On the plus side, hotel prices drop by a third and you’ll have the walls to yourself.

Practicalities without the checklist

Drive, and you’ll arrive via the A-4, exiting at kilometer 408. Follow signs for ‘Centro Histórico’ but stop when the street width shrinks to a single car plus two wing-mirrors; the free car park outside the walls is two minutes on foot and your paintwork will thank you. If you’re on public transport, the train station sits 2 km south of town—no taxi rank, no Uber, just a flat riverside stroll that takes twenty minutes. Friday is market day: leather espadrilles €8, mis-shapen cucumbers €1 a kilo, and the only place to buy a British-size pillowcase south of Córdoba.

Museums close on Monday, or open only 10:00-14:00 if the guard remembers his keys. The single ATM that reliably accepts UK cards is the Santander on Paseo de la Constitución—stock up before the weekend, when it, too, likes a rest. Finally, nightlife finishes early. Bars begin shuttering around 23:00; the last stragglers move to Plaza de España for gin-tonics served in fish-bowl glasses, but even they pack up before one. Plan accordingly, or bring a paperback and enjoy the sound of orange blossom settling on warm stone.