Full Article

about Almuniente

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

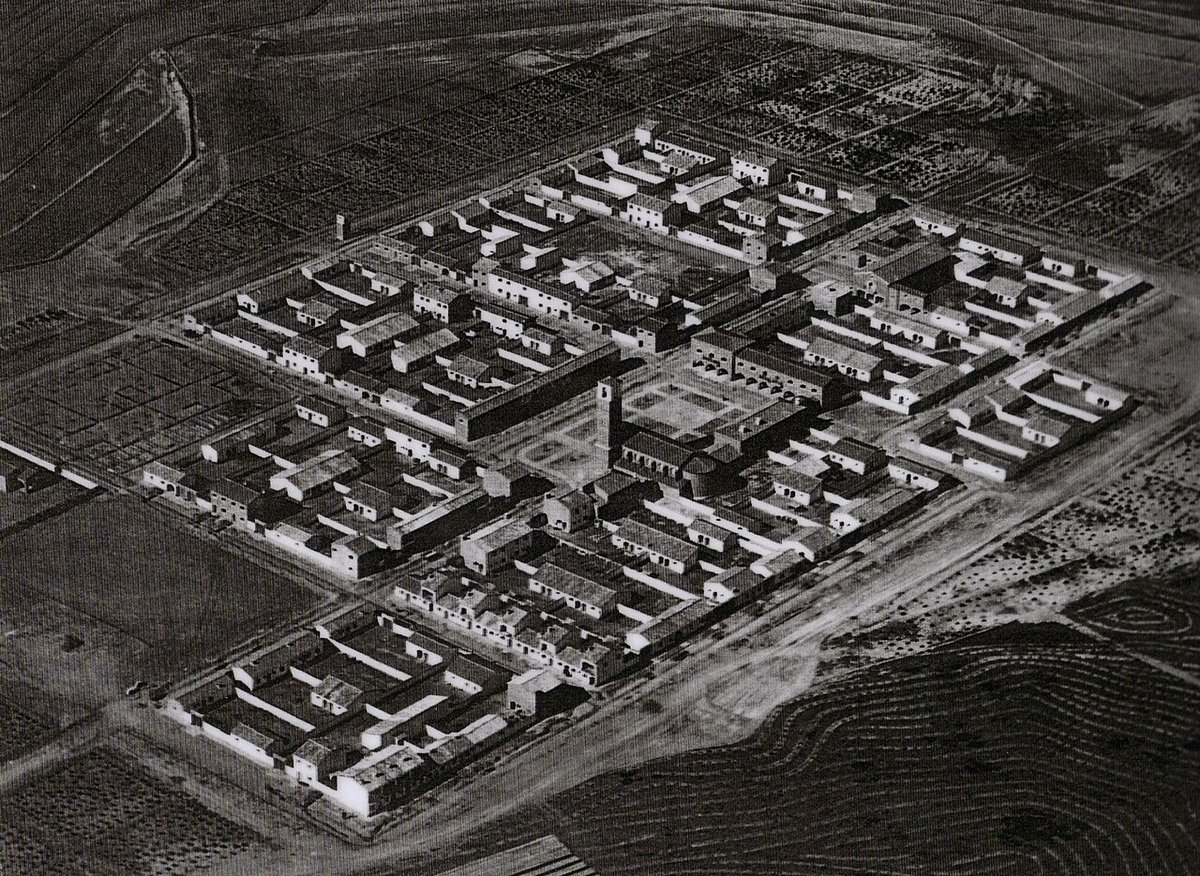

The church tower rises from the plain like a ship's mast from a golden ocean. For centuries, this has been the first thing travellers see when approaching Almuniente across the vast emptiness of Los Monegros. At 337 metres above sea level, the village sits exposed to every wind that sweeps across Aragon's high steppe, its stone and adobe houses huddled together for protection against a landscape that can turn from benevolent to brutal in minutes.

This is not Spain as imagined from British travel brochures. No whitewashed walls or palm-fringed beaches here. Instead, Almuniente offers something increasingly rare: a working Spanish village where agriculture still dictates the rhythm of daily life. The 440 inhabitants rise before dawn during harvest season, their movements governed by the cereal fields that stretch to every horizon. Tourism exists, but it plays second fiddle to the serious business of coaxing crops from semi-arid soil.

The Architecture of Survival

Wandering through Almuniente's compact historic centre reveals buildings designed for function rather than ornament. Local stone, thick adobe walls, and horseshoe arches speak of a practical response to extreme temperature swings. Summer mercury regularly hits 35°C, while winter nights can plunge below freezing. The houses, many dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, feature few windows on their northern faces and internal courtyards designed to catch cooling breezes.

The parish church dominates the modest skyline, its tower serving dual purposes: spiritual beacon and agricultural clock. When its shadow reaches the plaza's fountain at midday, workers know it's time for lunch. Inside, architectural elements from successive centuries sit side by side – Romanesque foundations support Gothic arches while Baroque additions compete for attention. The effect is less architectural confusion than honest evolution, each generation leaving its mark without erasing what came before.

Adobe construction, now fashionable in eco-building circles, remains commonplace here through necessity rather than trend. The mud-brick walls regulate interior temperatures naturally, staying cool during scorching afternoons and releasing stored heat after sunset. Several houses display original wooden balconies, their wrought-iron railings showing the skilled handiwork of local blacksmiths who understood that decoration could serve structural purposes.

Birds, Breezes and Baked Earth

The apparent monotony of the surrounding steppe rewards patient observation. Los Monegros harbours Europe's largest concentration of steppe bird species, making Almuniente an unlikely hotspot for British birdwatchers seeking something different from RSPB reserves. Dupont's larks, thought to number fewer than 3,000 pairs worldwide, breed in the sparse vegetation surrounding the village. Bring decent binoculars and prepare for early starts – these birds are most active during the cool morning hours.

Autumn brings migrating raptors overhead, with honey buzzards and short-toed eagles riding thermals south towards Africa. Local farmer José María Pérez knows the seasonal patterns intimately. "The birds tell us what weather's coming," he explains, gesturing towards wheeling vultures. "When they fly low, rain follows. When they soar high, the heat will stay."

Several footpaths radiate from the village, following ancient drove roads used for moving livestock between summer and winter pastures. The Ruta de los Antiguos Caminos, a 12-kilometre circuit, provides perspectives impossible to appreciate from the car. What appears flat from the roadside reveals itself as rolling countryside dotted with seasonal lagoons that appear after autumn rains. These wetlands attract flamingos and other water birds, creating surreal scenes as pink reflections shimmer against baked earth backgrounds.

Eating with the Seasons

British visitors expecting extensive menus will be disappointed. Almuniente's culinary offerings reflect its agricultural reality: local, seasonal, and substantial. The village's two restaurants, Mazmorra by Macera and Don Jaime 54, both maintain the Spanish tradition of menú del día – typically three courses with wine for under €15. Dishes arrive without artistic presentation but with flavours developed through generations of refinement.

Cordero al chilindrón, lamb stewed with peppers and tomatoes, appears on virtually every table during cooler months. The meat comes from animals that grazed on surrounding scrubland, their diet of wild herbs imparting distinctive flavours impossible to replicate in intensive farming systems. Migas, essentially fried breadcrumbs with garlic and chorizo, originated as field workers' fare but now features on restaurant menus. Don't expect delicate portions – these dishes were designed to fuel hard physical labour.

Spring brings tender vegetables and the brief asparagus season. Wild asparagus grows along field boundaries, and locals guard favourite foraging spots with typical Spanish secrecy. If offered revuelto de espárragos trigueros (scrambled eggs with wild asparagus), accept immediately. The season lasts barely three weeks, and finding restaurants serving it requires local knowledge or considerable luck.

When Silence Returns

August transforms Almuniente completely. The annual fiestas bring former residents back from Zaragoza, Barcelona, and beyond, temporarily swelling the population to over a thousand. Streets fill with generations of families reuniting, while the plaza hosts nightly concerts that continue until dawn. British visitors during this period experience authentic Spanish village celebrations, complete with processions, fireworks, and communal meals where outsiders are welcomed but remain conspicuously foreign.

The rest of the year returns to something approaching silence. Shops close for siesta promptly at 2pm. The single bar empties as workers return to fields. Evenings bring elderly residents to bench-lined streets, where conversations cover decades of shared history. Weather dominates discussion topics – a dry June means poor harvest yields, while September storms can ruin cereal crops ready for collection.

Winter access requires preparation. While major roads remain clear, the A-129 from Huesca can close during heavy snowfalls that occur perhaps once every three years. More problematic are the winds that accompany winter weather systems. Gusts exceeding 80 kilometres per hour aren't uncommon, making driving hazardous for high-sided vehicles. Summer visitors face different challenges – the exposed location offers no shade, and temperatures regularly exceed 40°C during July heatwaves.

Almuniente won't suit everyone. Those seeking entertainment complexes or extensive shopping should stay elsewhere. The village rewards visitors who arrive with time to spare and expectations adjusted to rural rhythms. Early mornings bring haunting beauty as mist rises from seasonal pools, while sunsets paint the steppe in colours that shift from gold through copper to deep purple. Between these daily markers of time's passage lies something increasingly precious – a place where Spain continues living as it has for generations, largely indifferent to tourism's whims and fashions.