Full Article

about Broto

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

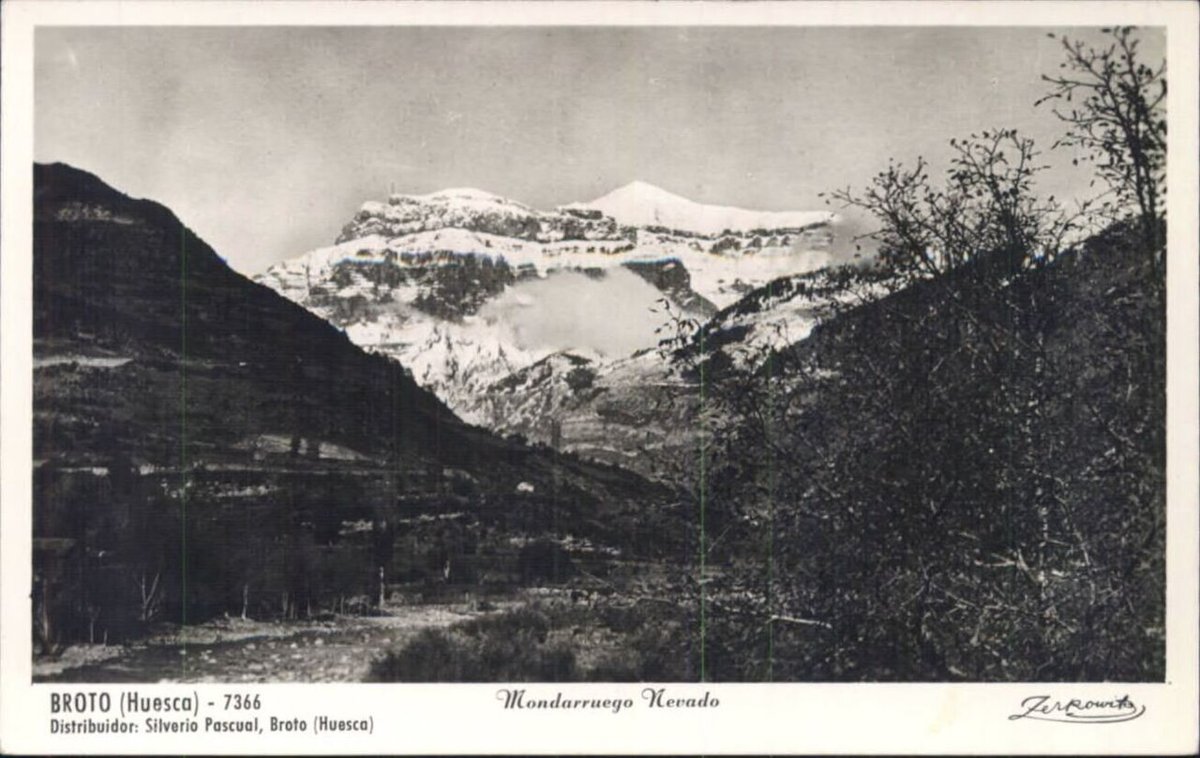

The church bells strike seven as the first sunlight hits Monte Perdido's limestone face. From Broto's main street, 905 metres above sea level, the transformation happens in real time: grey rock turns gold, shadows retreat up the valley walls, and another day of mountain weather begins its unpredictable cycle. This is what passes for rush hour here—light moving across stone rather than traffic moving through streets.

Morning Light on Stone and Water

Broto sits where the Ara River widens into a proper valley, twenty minutes' drive from Torla and the famous Ordesa Canyon. The village owes its existence to this confluence of geography: enough flat ground for houses, reliable water for mills, and a natural corridor for shepherds driving flocks between summer and summer pastures. The stone buildings reflect these centuries of adaptation—thick walls with tiny windows facing north, wooden balconies oriented south, and roofs pitched steep enough to shed winter snow but shallow enough to resist the tramontana wind.

The river provides the soundtrack. Even in August's heat, its glacier-fed waters run cold enough to numb feet in thirty seconds. A five-minute walk from the church square brings you to the Sorrosal waterfall, where meltwater drops seventy metres down a limestone cliff. The path is mostly level—built for donkeys, not hikers—though rockfall occasionally wipes out the final section. British visitors in flip-flops discover quickly why the Spanish wear proper footwear; the spray creates permanent moss that turns the stones into an ice rink.

Between Pasture and Parking

Wednesdays transform the quiet main street. Vendors from across Sobrarbe arrive before dawn, setting up stalls that sell everything from local cheese that smells of mountain herbs to hardware that hasn't changed design since Franco's day. The market draws pensioners who gossip in rapid Aragonese, weekenders from Zaragoza stocking up on embutidos, and the occasional bewildered tourist who wandered down from their hotel breakfast expecting postcards and finding jamón instead.

The hotels themselves tell Broto's recent story. Three decades ago, accommodation meant basic pensiónes catering to Spanish climbers. Now, renovated stone houses offer underfloor heating and rainfall showers, though the WiFi still struggles with the stone walls. Prices reflect the location rather than luxury—expect €80-120 for a double room in shoulder season, nearly double during August's climbing festivals. Rooms facing the river command premiums for the white-noise effect; those fronting the N-260 get lorry noise from dawn.

The Serious Business of Walking

Broto's real purpose reveals itself at breakfast. Hotel dining rooms fill with people studying weather apps and comparing route notes over strong coffee. The village serves as base camp for Ordesa Valley hikes, though Torla gets the tour buses. This geographical accident works in Broto's favour—walkers here tend to know what they're doing rather than following umbrella-waving guides.

The classic day hike starts with a twenty-minute drive to the Pradera car park, then follows the Ordesa Valley floor to the Cola de Caballo waterfall. Sixteen kilometres return, mostly flat, achievable by anyone who owns walking boots. More serious routes branch up the valley sides—Senda de los Cazadores climbs 800 metres in four kilometres, rewarding effort with views across to France on clear days. The limestone geology creates optical illusions; distances deceive, and what appears an easy hour's stroll often takes three.

Winter changes everything. Snow arrives by November, turning the village into a staging post for ski mountaineers heading into the high valleys. The road to Torla closes at the first serious snowfall—locals keep chains in their cars from October to May. Hotel occupancy drops to single figures, and restaurants switch to winter menus heavy on stews and local lamb. Prices fall accordingly; a double room that costs €120 in September drops to €60 in February, assuming you can reach it through the passes.

Food for Altitude

The dining scene reflects mountain priorities—calories over presentation, quantity over finesse. Local specialities arrive on plates that would shame a London gastropub: chuletón de ternera features steaks thick enough to require their own postcode, served bleeding-rare on wooden boards with potatoes that absorb the juices. The altitude affects cooking times; water boils at 95 degrees here, so vegetables stay firmer and rice takes longer.

Vegetarians face limited options. Most menus offer grilled vegetables or mushroom risotto as afterthoughts, though the Wednesday market sells excellent local cheese and honey for picnic lunches. The river provides trout for those with fishing permits—locals recommend early morning when the fish haven't wised up to human presence. Wine lists stick to regional varieties; Somontano reds handle the altitude better than Riojas, and cost half the price they'd command in London.

When the Weather Turns

Mountain weather deserves respect. Summer storms build through afternoon heat, arriving with spectacular thunder that echoes off the valley walls. Hikers caught above the tree line scramble down as granite-dark clouds pile up, releasing hail that turns paths into rivers within minutes. The village's stone buildings have weathered centuries of this; modern visitors discover that "waterproof" means something different at altitude.

Spring brings meltwater floods that occasionally close the main road. Autumn delivers perfect walking weather—cool mornings, warm afternoons, and valley views that stretch for fifty kilometres. But autumn days shorten quickly; that leisurely lunch in a mountain refuge becomes a race against darkness if you mistime the descent. Local guides tell stories of British walkers benighted with nothing more than a phone torch and a packet of biscuits, waiting for rescue at dawn.

The Long View

Broto won't charm you in the way of chocolate-box villages. It's too functional, too obviously built for survival rather than aesthetics. The main road cuts straight through, summer crowds clog the narrow streets, and August temperatures can hit thirty-five degrees in the valley bottom. Yet it offers something increasingly rare—a place where geography still dictates daily life, where weather decides plans, and where five hundred people have learned to live with forces that would overwhelm most British towns.

Come for the hiking, stay for the evening light on the peaks, and leave before the first snow. Or stay for winter, when the village returns to its true self—quiet, self-sufficient, and indifferent to whether visitors arrive at all. Just remember to bring cash; the nearest ATM is twenty kilometres away, and mountain honesty hasn't yet embraced contactless payments.