Full Article

about Castiliscar

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The wheat around Castiliscar ripens so fast you can hear it crackle. By late June the fields have turned from green to gold in a fortnight, and the combine harvesters start at dawn, long before the sun makes the metal too hot to touch. From the village edge the machines look like bright toys crawling across a biscuit-coloured carpet, leaving tidy rows of stubble that smell of dry earth and split straw. It is the sound of money being made, of school fees in Zaragoza and new tyres for the Land Rover, and it drowns out the church bell that strikes every half-hour from the tower at the top of the hill.

A grid of stone and silence

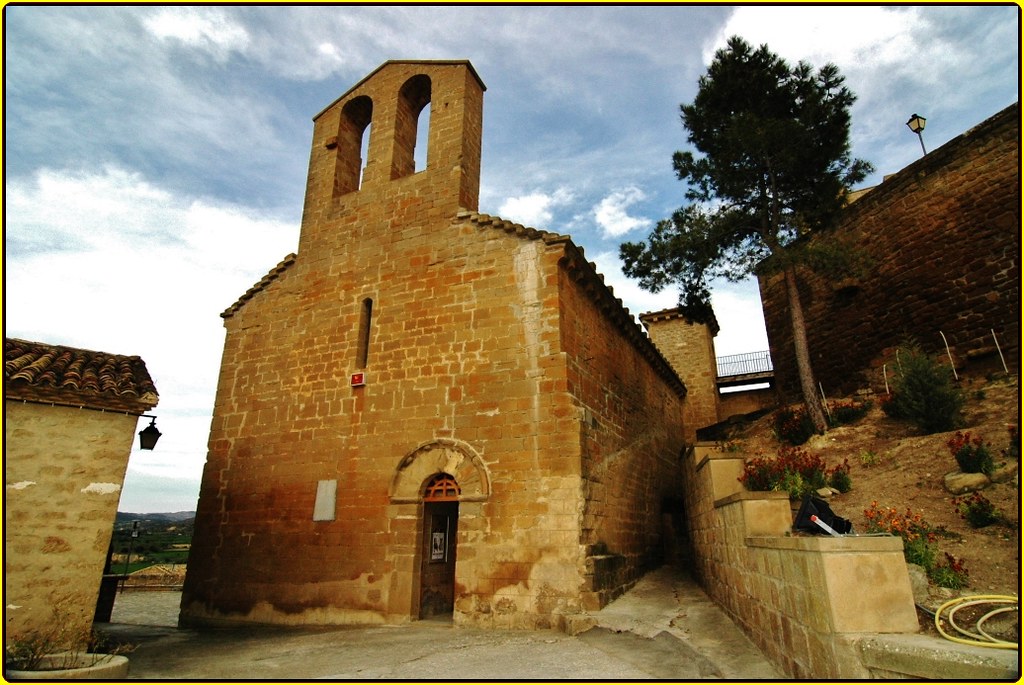

Two hundred and thirty people live here permanently, enough to keep one bar open year-round and the primary school going with twelve pupils. The streets were laid out in the twelfth century to confuse raiders from Navarra; they still do a good job of disorienting visitors. Houses are built from the same ochre limestone that crops out in the surrounding fields, so the whole village appears to have risen out of the ground rather than been dropped on it. Rooflines are irregular, walls swell and taper, and every now and then a medieval stone lintel carved with a cross or a boar’s head sits above a garage door that was cut through the façade in 1978.

There is no souvenir shop, no interpretive centre, no brown sign pointing to a “mediaeval experience”. The tourist office is a laminated A4 sheet taped inside the bar window, giving the mobile number of Pilar, who will unlock the church if she is not out with the sheep. Entry is free; the light is best at seven in the evening when the sun slants through the south portal and picks out the faint fresco of Saint Michael that was rediscovered during a 1996 repair. He weighs souls in a pair of iron scales; a tiny devil with a farmer’s face tugs at the lighter basket.

What to do when nothing is on

Walk. The public footpaths are farm tracks, graded gravel that turns to powder underfoot in August. One heads east towards the ruins of a Roman dam, now no more than a curved earth bank edged with poplars; another climbs north to a ridge where you can see the Pyrenees on a clear day, snow still whitening the highest summits while lizards scurry over baking slate at your feet. The GR-1 long-distance trail brushes the village boundary, but most hikers hurry past, bound for the loftier villages of the Cinco Villas. Their loss: the 6-kilometre circuit through the barranco de las Cuevas takes forty-five minutes, requires no specialist footwear, and ends at the bar, which keeps cold cans of Ambar beer in a freezer cabinet because the fridge motor is sometimes unreliable.

Cycle. Road bikers love these lanes. Traffic averages six cars an hour, half of them driven by neighbours who will wave you through the dust cloud they create. The gradient is gentle, the tarmac patchy; carry two tubes because thorns from the wayside blackberries have a talent for finding latex. A loop south to Sádaba and back via Layana is 38 km, includes one 3-kilometre drag at 5 %, and finishes with a view of Castiliscar that makes the village look like a ship riding a sea of wheat.

Eat. Saturday lunchtime is the only safe bet. That is when Marisol fires up the kitchen in the bar and serves roast lamb shoulder that has spent four hours in an oven built into the old bread alcove. €14 buys meat, chips, a plate of roasted peppers from her brother’s greenhouse, and a jug of water drawn from the village spring. Vegetarians get migas—breadcrumbs fried with garlic and grapes—because that is what the calendar says; asking for tofu will be treated as a joke in poor taste. If you need dinner, phone before 19:00; if nobody answers, plan on bread, cheese and a bottle of Garnacha bought earlier in Ejea de los Caballeros.

The calendar that matters

Visit in late April and you will see the sheep being driven through the main street to summer pasture; the shepherd still rings a handbell rather than uses a mobile, because the 4G signal dies at the first hill. Mid-August brings the fiesta patronal: inflatable castles in the plaza, a foam party that empties the village pool, and a Saturday-night dance that finishes when the generator runs out of diesel. Book accommodation early—there are four rooms in a rebuilt hayloft, €45 a night, breakfast of coffee and churros included—or you will end up sleeping in your hire car, a fate that last year befell a couple from Brighton who assumed “rural Aragon” meant “plenty of room”.

Come in September for the grape harvest. The vines are not regimented rows on a boutique estate but scattered plants clinging to south-facing garden walls; the fruit is sweet enough to eat like sweets and the juice stains fingers a violent purple that no amount of lemon will shift. A week later the first almonds are knocked down with long canes; children get 50 cents a kilo for picking them up, and the whole village smells of marzipan when the cooperative machine on the edge of town starts shelling.

Getting here, getting out

Zaragoza airport, an hour and twenty minutes away, has direct Ryanair flights from London-Stansted three times a week outside winter. Hire a car at the terminal: the Goldcar queue is shorter but the fuel policy is punitive; pay the extra €30 for full-to-full with Enterprise. Take the A-68 towards Pamplona, exit at junction 22 for Gallur, then follow the C-127 for 13 km. The road narrows after the grain silo; watch for tractors pulling wide cultivators at dusk with no lights. Petrol is 8 cents cheaper in Gallur than the airport—fill up, because Castiliscar has no station and the nearest alternative is a 24-hour pump in Ejea that swallows only Spanish cards after 22:00.

There is no cash-point. The bar takes cards but the system crashes during storms; carry twenty-euro notes and a pocket of change for coffee. Public transport is the school bus that leaves at 07:10 and returns at 14:30; visitors are politely discouraged from boarding because it is subsidised by the regional government and seats are allocated by surname.

The honest verdict

Castiliscar will not change your life. You will not tick off a UNESCO site or brag about a Michelin meal. What you will get is an unfiltered version of Aragon: a place where the evening news is still read aloud in the bar, where the mayor doubles as the plumber, and where the landscape obeys the seasons more than the tourist board. Bring walking boots, a phrasebook, and a tolerance for siesta hours that stretch from 14:00 until the temperature drops below thirty. Arrive expecting silence, stone, and the smell of straw heated by the sun. Anything else is a bonus; anything less means you arrived with the wrong list.