Full Article

about Cosa

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell strikes noon, but nobody hurries. In Cosa, time moves at the pace of cloud shadows crossing the Jiloca valley. At 1,185 metres above sea level, this hilltop village watches over Aragon's sweeping cereal plains from a vantage point that makes even seasoned walkers pause to catch their breath—not from exertion, but from the sudden realisation of how vast this corner of Spain really is.

The Village That Winter Built

Cosa's stone houses huddle together for good reason. When January winds whip across the paramo, temperatures plummet well below freezing. The local architecture tells this story: thick masonry walls, small windows, and doors that open onto narrow lanes where neighbours once gathered their livestock for protection. These aren't picture-postcard cottages but working buildings designed for survival at altitude.

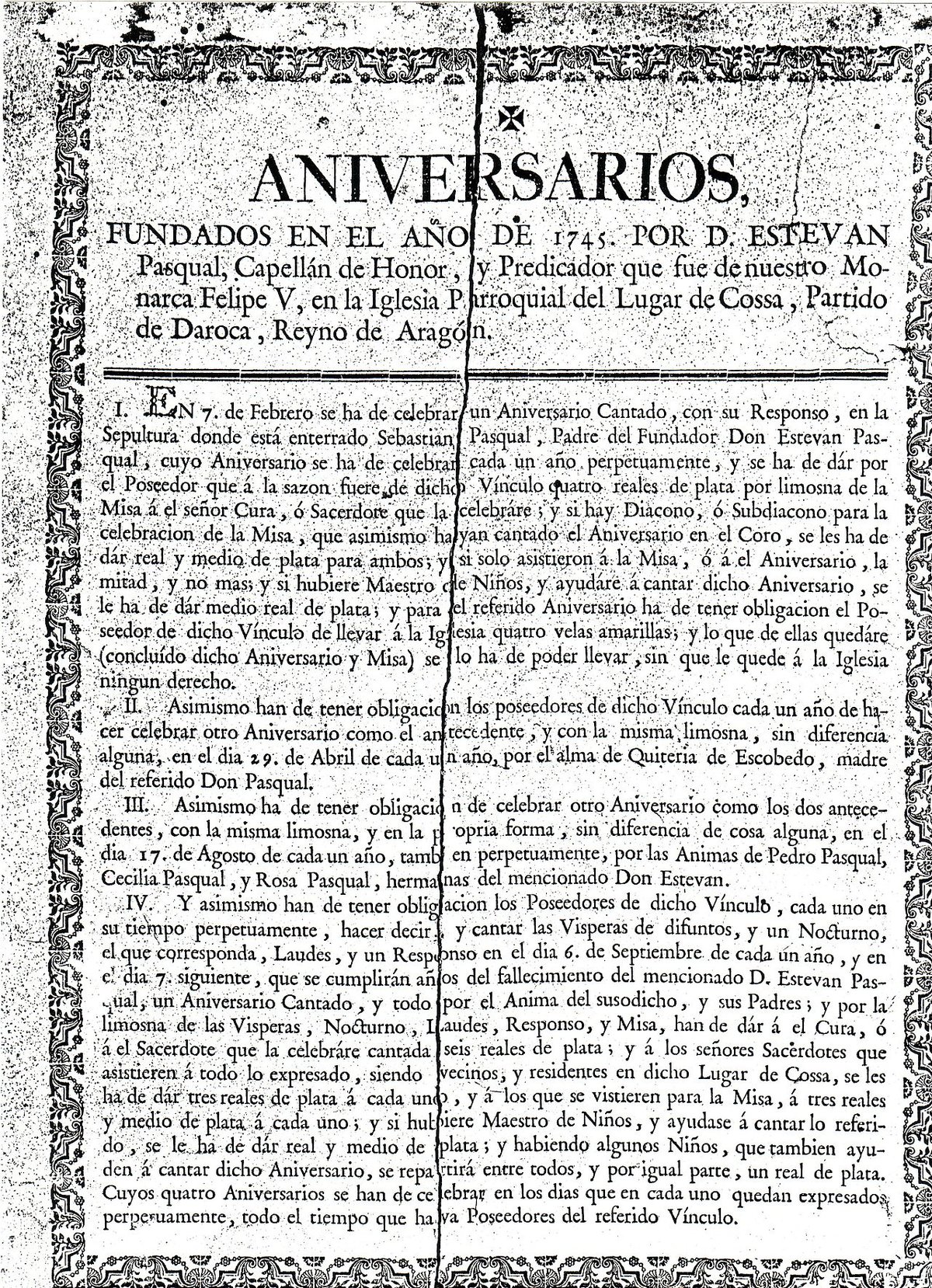

The parish church stands as testament to this pragmatic approach. Built from the same limestone that carpets the surrounding hills, its sturdy bell tower doubles as a landmark for farmers working distant fields. Inside, simple rural craftsmanship replaces baroque ornamentation—this is a place of worship for people who measure wealth in harvests rather than gold leaf.

Walking the village takes twenty minutes if you dawdle. Streets climb gently from the small plaza, past houses where geraniums spill from window boxes despite the altitude. Some properties stand empty now, their wooden doors weathered to silver-grey. Others show signs of weekend visits—fresh paint, new roofs, the occasional satellite dish pointing skyward like a prayer to modernity.

Between Earth and Sky

The relationship between Cosa and its landscape defines daily life here. Spring arrives late at this elevation; almond blossom appears weeks after the valley floors turn white with flowers. Farmers plant barley and wheat in soils so thin that rock breaks through like bones through skin. Yet somehow crops grow, ripening to gold under summer sun that feels closer, sharper, than at sea level.

Walking tracks radiate from the village like spokes from a wheel. The most straightforward follows an old grain trail eastward, contouring around hillsides before dropping to a dried stream bed where wild thyme releases its scent underfoot. Two hours of steady walking brings you full circle, though few visitors realise this counts as proper mountain terrain. The altitude means weather changes fast—what starts as a pleasant stroll can end in horizontal rain with visibility down to metres.

Birdwatchers bring binoculars for good reason. The mosaic of cereal fields and Mediterranean scrub supports species rarely seen in Britain. Dartford warblers scratch among the rosemary while short-toed eagles circle overhead, scanning for snakes that warm themselves on south-facing rocks. Dawn and dusk provide the best sightings, when soft light turns the plains ochre and silhouettes everything against endless sky.

The Taste of Altitude

Local cooking reflects both altitude and isolation. In Cosa's single bar-restaurant (open weekends only, phone ahead), the menu changes with what's available rather than what tourists might fancy. Migas—breadcrumbs fried with garlic, paprika and whatever meat needs using—appears regularly. So does ternasco, the young lamb that defines Aragonese cuisine, cooked slowly until it threatens to fall from the bone.

The house wine comes from Calatayud, forty kilometres distant. At these prices—glasses cost less than a London coffee—nobody's pretending it's grand cru. But it washes down hearty food while you listen to farmers discussing rainfall figures and wheat prices in rapid Aragonese Spanish that even mainland Spaniards struggle to follow.

Sweet-toothed visitors should time their arrival for festival periods when locals bake traditional pastries. These aren't delicate patisserie but substantial creations designed to feed extended families: honey biscuits that last weeks, almond cakes dense enough to survive mountain transport, and the anise-flavoured rolls that accompany Sunday coffee in farm kitchens across the comarca.

When the Village Returns to Life

August transforms Cosa. The population multiplies as families return for fiestas patronales, cars lining lanes too narrow for modern vehicles. Grandparents who've maintained year-round vigilance over empty houses suddenly find themselves cooking for twenty. Children who've grown up in Zaragoza or Barcelona rediscover fields where their parents once played.

The church procession weaves through streets decorated with paper chains and handmade banners. Following behind, visitors realise they're participating in something genuine—not a folkloric display but a community asserting its identity. The brass band might be slightly out of tune, the fireworks modest compared to municipal displays back home, but the pride feels authentic enough to touch.

Evenings centre on the plaza. Long tables appear bearing paellas large enough to feed armies. Strangers find themselves handed plates and drawn into conversations that mix Spanish with local dialect. Someone produces a guitar; others sing songs that predate Spotify playlists by centuries. As midnight approaches, teenagers who've spent holidays here since childhood slip away to the fields, carrying on traditions their grandparents pretend not to notice.

Practical Realities

Getting here requires commitment. From Teruel, the N-234 heads northwest through landscapes that grow increasingly empty. Turn off at Calamocha, follow smaller roads that twist through wheat fields, then climb steadily for twenty minutes. The final approach reveals Cosa perched on its ridge like an eagle's nest—spectacular unless you're the driver navigating hairpin bends while avoiding oncoming tractors.

Public transport doesn't exist. Rental cars from Teruel cost around £40 daily, though book ahead—availability proves limited outside August. Winter visitors should check weather forecasts religiously. Snow chains become essential when Atlantic storms meet continental cold; the road from Calamocha closes several times each winter.

Accommodation means either booking into the village's three guest rooms (basic but clean, €35-45 nightly) or basing yourself in Calamocha twenty minutes distant. The latter offers proper hotels and restaurants, but you'll miss dawn light washing across the plains and night skies so dark that Milky Way viewing requires no specialist equipment.

Spring and autumn provide the sweet spot for visiting. April brings wildflowers to road verges while temperatures remain cool enough for serious walking. October paints cereal stubble gold against purple thyme, with crisp air that makes coffee taste better somehow. Summer delivers perfect conditions for star-gazing—bring layers regardless of daytime heat.

Cosa won't suit everyone. Those seeking boutique hotels, Michelin stars or nightlife should stop in Calamocha. But travellers who've grown weary of Spain's costas, who wonder what lies beyond the beach resorts and city breaks, might find exactly what they didn't know they were looking for: a place where elevation provides perspective in the most literal sense, where community survives through stubbornness rather than strategy, where the simple act of watching sunset from a church square feels like discovering something important about how people really live when nobody's watching.