Full Article

about Lobera de Onsella

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

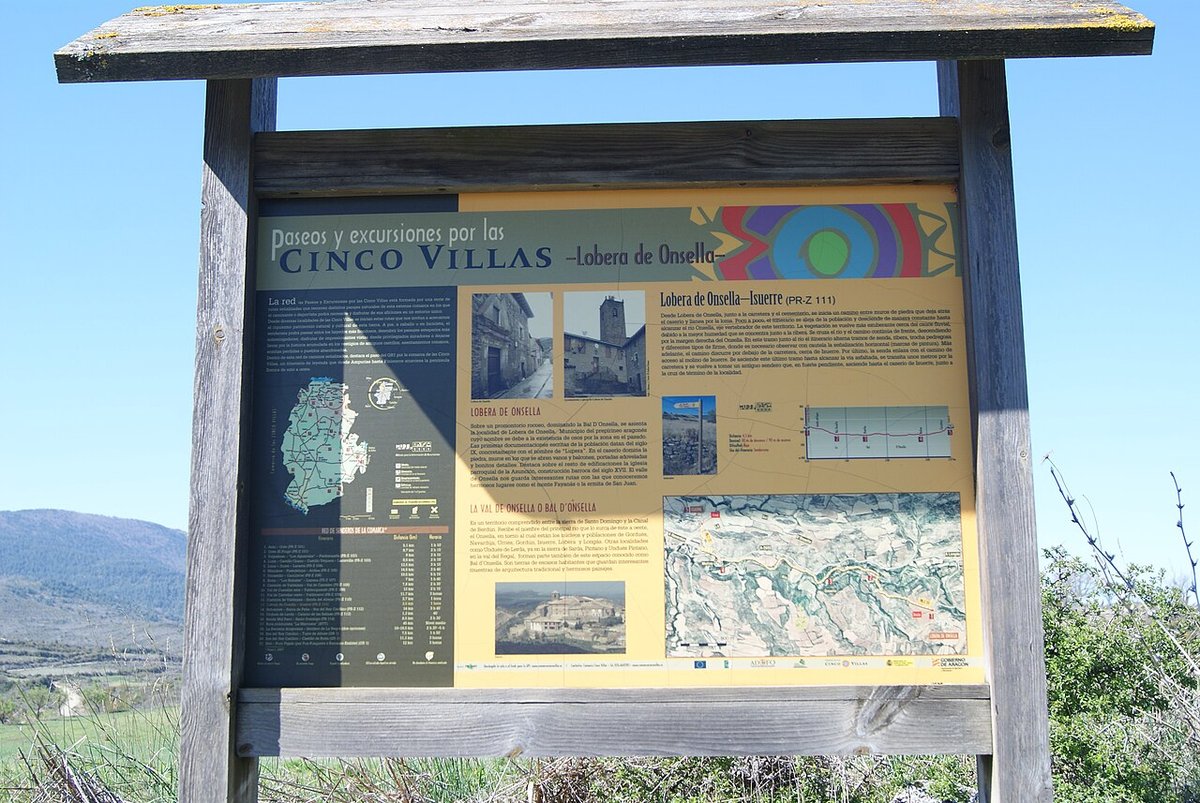

The church bell strikes three and every dog in Lobera de Onsella takes it as a cue. Barking ricochets through lanes barely wide enough for a tractor, scattering the only audience in sight: three sparrows and a pensioner in a quilted jacket. At 672 m above the Ebro basin, sound carries. So does the wind, which today smells of damp earth and the sheep farm on the ridge. Twenty-six residents are officially listed; the real head-count depends on who has driven to Ejea de los Caballeros for the weekly shop.

Stone-and-adobe walls the colour of burnt cream rise on either side of the single through-road. Some have fresh grout, others breathe through fist-sized holes where plaster has given up. A wooden balcony leans so confidently that passers-by step into the gutter, half-expecting a theatrical creak. This is not a film set; it is simply a village that refused to become a ruin, even after the school closed in 1973 and the bar followed in 2009. The only commerce still breathing is a clapboard grocery open Saturday mornings—honour box on the counter, fridge humming louder than the proprietor.

Walk past the church, whose brick bell-tower was rebuilt after lightning in 1958, and the tarmac dissolves into a farm track. Within five minutes the cereal fields take over, rolling like a calm sea towards the faint blue line of the Pyrenees sixty kilometres north. There are no signposts, only the occasional spray-painted number on a electricity pole. A farmer in a white van waves; whether it is greeting or warning is unclear until he brakes and points to a boot-print shaped cloud on the horizon. Chubasco, he says—local dialect for a squall that can dump April hail on shorts-clad hikers. Take the hint, turn back, and the village re-appears as a dark knot on the ridge, its few tiled roofs glinting like wet slate.

Afternoon calories, evening darkness

Eating on site requires planning. The single restaurant, El Jabali, opens only at weekends outside August; mid-week visitors should ring ahead or expect a closed door and a lingering smell of last weekend’s roast lamb. Inside, the menu is short: migas fried in chorizo fat, stripey pink longaniza sausage from nearby Uncastillo, and lamb shoulder that collapses at the sight of a fork. House wine comes from Somontano, thirty-five minutes by car, and costs €12 a bottle—less than two London bus fares. Vegetarians get eggs, cheese, and apologies.

Those staying overnight have one option: Casa Rural Bal d’Onsella, a three-key house on the upper lane. Reviews grumble about thin pillows and the church bell, but praise the firewood stash and the owner’s directions to the nearest cash machine (seven kilometres). At €70 for the whole ground floor, spring weekdays are quiet enough to choose your bedroom like a picky Goldilocks. There is no mobile signal upstairs; WhatsApp withdraws to the kitchen window, where the glass vibrates whenever the bell tolls the hour.

Night falls fast. The council replaced half the streetlights with LEDs, then ran out of budget, leaving pools of bruised orange between stretches of proper dark. Bring a torch; cobbles are uneven and the village cat is black. Stand beyond the last lamp and the sky delivers a geography lesson: the summer triangle, Scorpius scraping the southern hills, satellites gliding like silent trams. Light pollution registers 21.4 on the Bortle scale—darker than most of Dartmoor. A shooting star erases itself over Huesca; somewhere below, a dog answers with a single bark.

Why stop at all?

Motorway travellers sometimes divert here out of curiosity, having seen the name on a brown sign from the A-127. They park, photograph the medieval arch that isn’t medieval (rebuilt 1994), buy nothing because nothing is open, and leave ten minutes later. That misses the point. Lobera works as a palate cleanser between the big ticket towns: an hour from mediaeval Tarazona, forty minutes from the Roman walls of Uncastillo, twenty from a Michelin-starred menu in Ejea if you suddenly need foam and rosemary smoke. Arrive at midday, walk the grain-circle paths until trainers are dusted beige, eat where locals eat on feast days, and leave before the afternoon slump. The village will not mind; it has seen empires come and go.

If you insist on an itinerary, try this: start at the 16th-century baptismal font inside the church (open only before Mass on Sunday), follow the sheep-farm lane east until the grain silo shaped like a submarine, then cut back through the holm-oak hollow where wild irises bloom in May. Total distance: 4 km, negligible gradient, maximum reward-to-effort ratio. Finish with a thermos on the stone bench outside the locked school; the playground mural, painted by the last class in 1973, shows a sky that is still the same shade of Spanish blue.

The August exception

For eleven months the village practises social distancing by default. Then the feast of the Assumption lands and cousins materialise from Zaragoza, Barcelona, even Birmingham. Population swells to 120, handbags open like deck-chairs in the plaza, and someone’s uncle wires the church bell to a sound system that plays Queen at 2 a.m. The grocery becomes a bar; the grocery owner’s sister becomes a deejay. Outsiders are welcome, but this is not a tourist fiesta—it is a family reunion that happens to spill into the street. Book accommodation early or expect to sleep in your car, engine ticking itself cool under starlight that still refuses to be outshone.

Come the third week of August the exodus reverses. Cars laden with unfolded cots and half-eaten polvorones queue at the single petrol pump in Ejea; Lobera exhales, the last firework case is swept away, and silence re-settles like dust. The village cat reclaims the bench, the church bell remembers its job, and twenty-six names appear again on the register—twenty-seven if someone’s aunt misses the motorway turn-off and stays an extra night.

Getting here, getting out

From the UK, fly to Zaragoza (Stansted, £38 return in shoulder season), collect a hire car, and head west on the A-68 for 45 minutes. After exit 22 the landscape unclenches; wheat gives way to sunflowers, then to the steeper mosaic of drystone walls that announces Cinco Villas. The final six kilometres wriggle uphill on the A-127; watch for tractors around the bend before the Lobera sign. Fuel the tank before leaving the motorway—village pumps closed years ago. winters can trap cars after sudden snow; if you visit between December and March, carry chains and the phone number of the local farmer who owns a 4×4. He charges €30 for a tow and tells the story, short version, of every stranded motorist since 1987.

Leave the same way, or thread south through undervisited Sos del Rey Católico, then west to the wine dark of the Bardenas Reales, half an hour away. Look in the rear-view mirror: Lobera shrinks to a single smear of stone on the ridge, indistinguishable from the outcrops that once gave wolves shelter—hence the name. The road dips, the ridge disappears, and the 21st century re-enters the car by increments: phone signal, billboards, the first roundabout with a supermarket that stays open all day.