Full Article

about Munebrega

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell strikes seven and the only other sound is the wind pushing through wheat stubble. From the stone bench beside the cemetery wall you can watch the sun lift over 40 kilometres of empty plateau, broken only by the thin spire of another village church far to the south. This is Munebrega at daybreak: 356 inhabitants, 749 metres above sea level, and silence so complete it takes a morning to get used to.

A Plateau that Breathes

The village sits on a low rise scraped clean by centuries of northerly cierzo wind. Houses are built from the same ochre stone they stand on, roofs pitched to stop the tiles lifting in winter gales. Walk ten minutes in any direction and the land drops away, revealing a chessboard of cereal fields that change colour almost weekly—emerald after autumn rain, biscuit-coloured by July, silver when the stubble catches the light. Bring binoculars: kestrels use the thermals, and in May you can watch flocks of calandra lark rising like ash from the plough.

There is no dramatic gorge, no cliff-top castle, just space. British visitors who arrive expecting postcard Spain need a moment to recalibrate. What you get instead is scale: kilometre after kilometre of sky, horizons that seem curved, and a night sky dark enough for the Milky Way to cast a shadow. Light-pollution maps show this pocket of Aragon in the same category as mid-Atlantic.

Stone, Adobe and the Odd wonky Balcony

Munebrega's centre is a triangle of three streets—Calle Mayor, Calle San Pedro, Calle de la Cruz—wide enough for tractors to pass. Many façades were patched rather than restored, so nineteenth-century stone ground floors support 1970s brick upper storeys, and the occasional wooden balcony leans at angles that would give a surveyor nightmares. The effect is honest: no film-set uniformity, just a working village that happens to have stayed small.

The parish church keeps its tower door unlocked. Inside, the air smells of candle wax and damp stone; the only artwork is a faded sixteenth-century fresco of Saint Michael whose scales of justice have almost vanished. Locals pop in to water the plants, then leave again, pulling the door gently shut behind them. Tourist offices elsewhere hand out leaflets; here you get a nod and the feeling you've been trusted with the keys.

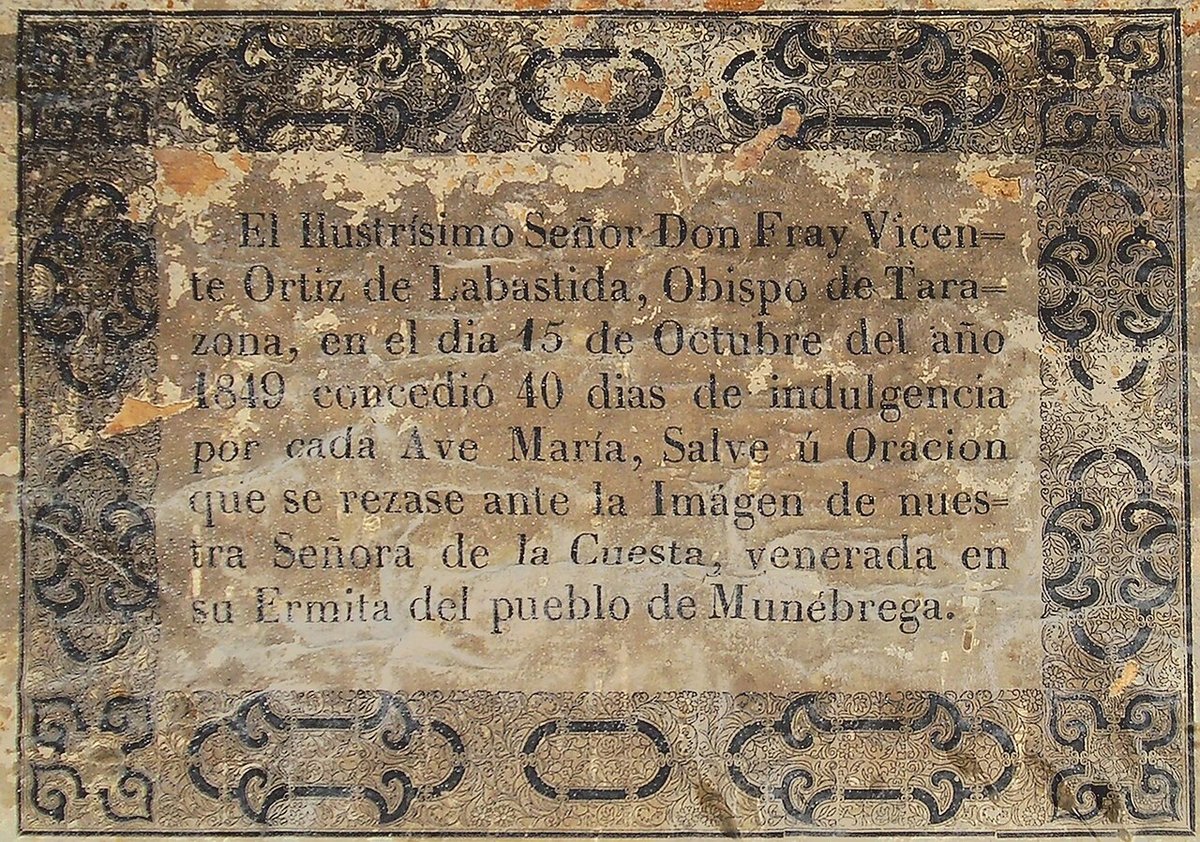

Five minutes east, a dirt track leads to the ermita, a single-cell chapel built when the population was three times today's. The door is usually locked, but the forecourt is the village's highest point: 360-degree views across the Jalón valley, the Moncayo massif snow-capped from November to April, and the zig-zag line of the A-2 motorway, tiny as a model railway, carrying traffic between Madrid and Barcelona.

What to Do When There is Nothing to Do

Forget tick-box sightseeing. The main activity is walking the old caminos that linked farmsteads before anyone here owned a car. A favourite loop heads south for 6 km to the abandoned hamlet of Aldehuela, returning along the irrigation channel built by Moorish farmers. Paths are unmarked but obvious: two ruts and a middle strip of weeds. Stout shoes suffice; poles are overkill. In April the verges are studded with red poppies and the air smells of fennel; by late June the same earth is powdery and grasshoppers snap past your ankles.

Road cyclists rate the local circuit "lumpy rather than savage". Roll out north-east towards the Cariñena wine district and you meet a 12-km false flat followed by a 4-km climb at 4 %. Traffic averages one vehicle every nine minutes according to the regional road census, but Spanish drivers treat narrow lanes like motorways, so keep ears open. Mountain bikers can link farm tracks to create a 35-km loop through six villages; download the GPX file at the hostal reception because signposts don't exist.

Evening entertainment is the bar beside the church. Doors open at eight, television stays on mute, and the landlord pours Cariñena joven from a tap sunk into the wall. A glass costs €1.80, a plate of migas—fried breadcrumbs laced with grapes and bits of pancetta—adds €5. On Fridays someone brings a guitar; by 11 pm half the village seems to be inside, argument ranges from barley prices to whether Real Zaragoza will ever return to La Liga, and you remember why Spanish night-life starts when British pubs are calling last orders.

Eating (and Stocking Up)

The village has one grocer, Coviran, size of a corner shop in Sheffield. Shelves carry UHT milk, tinned beans, local olives and not much else. Serious supplies require a 20-minute drive to Calatayud: Mercadona for fresh fish, bakery for decent baguettes, and a petrol station because the single pump in Munebrega closed two years ago.

Restaurants follow the same rule as shops—there aren't any, only the bar. Meals are served at wooden tables that wobble on the uneven flagstones. House specialities are designed for harvest workers: chuletón al estilo aragonés, a T-bone that covers the plate, grilled only until the fat edge crisps; caldereta de cordero, a hearty lamb stew thickened with bay and saffron; torrijas for dessert, cinnamon-dusted bread soaked in wine and honey. Vegetarians get tortilla Española or a salad of grated tomato on toast. Prices feel stuck in 2010: three courses with wine rarely tops €18.

Sunday lunch is the sociable meal. If you book a self-catering studio, buy the ingredients on Saturday because the baker shuts at noon on Sunday and won't reopen until Tuesday. Arrive at the bakery after 11 a.m. and you'll find the counter empty—every grandmother in the village has already carried off the last barras.

Seasons and How They Feel

Spring arrives late at this altitude. Almond blossom appears in mid-March, wheat follows three weeks later, and nights stay cool enough for a jumper until early May. By June the plateau becomes a suntrap; temperatures touch 34 °C but humidity is low, so walking is still pleasant if you start before nine. July and August are fierce: 38 °C by 3 p.m., cicadas screaming from the lone plane trees, streets empty except for the elderly shuffling to the shade of the church porch. Accommodation without air-conditioning is miserable—check before booking.

Autumn is the locals' favourite. Harvesters work under clear skies, the smell of straw drifts into the village, and the bar sets tables outside again. In October the Moncayo ridge behind you turns the colour of burnt toast; by November the first snow appears on the highest crest and the wind sharpens. Winter days can be T-shirt warm in sunlight but drop to –5 °C after dark. The hostal switches on heating reluctantly—ask for extra blankets rather than expecting tropical interiors.

Getting There, Staying There, Leaving

No railway, no regular bus: you need wheels. Fly Ryanair from London-Stansted to Zaragoza (2 h 10 m), collect a hire car, and head west on the A-2 for 75 minutes. The turning is signposted "Munebrega 6 km" just after a wind-farm; the road climbs, narrows, then suddenly you're in the main square with free parking everywhere. Alternative route: BA or Vueling to Madrid, AVE train to Calatayud (1 h 15 m), pick up a rental there and drive 25 minutes. Petrol stations on the Spanish motorways close at midnight; fill up before leaving the A-2 if you arrive late.

Accommodation is limited to two options. Hostal Rey Mundo offers 14 studios built around a small pool (open June-September only). Rooms have kitchenettes, decent Wi-Fi and views straight over wheat fields; doubles from €60 mid-week, €75 at weekends. Alojamientos Mundobriga, 200 m away, is a row of converted farm buildings with thicker walls—better insulation in winter, no pool, slightly cheaper. Both accept dogs for a €10 supplement. August books up with returning emigrants; reserve early or arrive prepared to drive 30 minutes to the nearest alternative in Calatayud.

When it is time to leave, the checkout process is refreshingly Spanish: hand over the key, answer "¿Todo bien?" with a nod, and that's it. No minibars to audit, no car park ticket to validate. Pull away down the hill, rear-view mirror filled with receding fields, and the plateau quickly swallows the village whole. By the time you reach the motorway Munebrega feels less like a place you visited and more like something you briefly belonged to—an impression that lingers until the first service station coffee brings you back to the twenty-first century.