Full Article

about Olvena

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

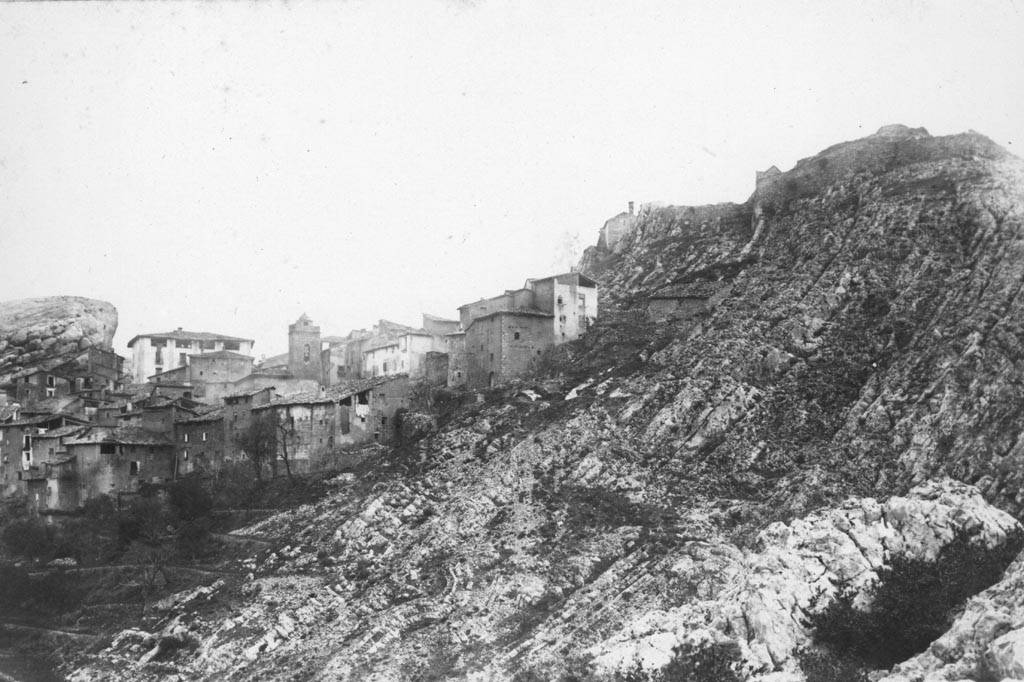

The church bell strikes eleven and only three people move through Olvena's single street. One carries a ladder, another a crate of peaches, the third simply walks with hands clasped behind his back, watching cloud shadows drift across cereal fields that roll away towards the Sierra de Guara. At 522 metres above sea level, this Aragonese village doesn't so much sit on its hilltop as grow from it, stone by stone, generation after generation.

Sixty-seven souls call Olvena home now, though the census never quite captures the rhythm of departure and return. Young people leave for Zaragoza or Barcelona, grandparents hold the fort, and every August the population swells as descendants drift back for the fiestas. The houses tell this story plainly: some restored to weekend perfection with geranium-filled balconies, others quietly weathering another winter behind heavy wooden doors that haven't seen paint since Franco's day.

The Architecture of Everyday Life

There's no cathedral, no castle, no plaza mayor lined with souvenir shops. Instead, Olvena offers something British visitors rarely encounter anymore – a village built for work, not display. The parish church anchors everything, its modest bell tower rising just high enough to summon workers from the surrounding fields. Built from the same honey-coloured stone as every other building, it demonstrates the Aragonese principle that function beats ornament every time.

Wander the narrow lanes and you'll spot the tell-tale signs of rural Mediterranean life: ground-floor doorways wide enough for a donkey and cart, first-floor balconies just deep enough for drying peppers, flat roofs where women once spread almond shells to burn in winter stoves. The newer restorations favour glass and stainless steel, but most houses still wear their original uniform of rough stone walls and Roman-tile roofs, each tile hand-shaped from local clay and heavy enough to withstand the cierzo wind that roars down from the Pyrenees.

Photographers arrive seeking golden hour shots, and they find them – not in dramatic mountain vistas but in the way evening light catches the texture of a weathered doorframe, or how sunrise paints the cereal fields the colour of toasted brioche. The landscape here runs horizontal, not vertical, a patchwork of wheat, almonds and vines that changes from emerald to gold to brown with the agricultural calendar.

Working the Land, Tasting the Results

The menu at Bar Casa Julian changes daily depending on what appears at the back door: perhaps wild asparagus from the river banks, or a leg of lamb from a farmer celebrating his granddaughter's baptism. Julian's wife Conchi makes the kind of tortilla that would cause riots in London brunch spots – thick, golden, infused with olive oil pressed from olives grown on the village's edge. A plate costs €8, served with bread baked in Barbastro and tomatoes that actually taste like tomatoes.

The surrounding fields aren't scenery – they're the village larder. Almond trees planted by Julian's grandfather now produce the nuts that appear in everything from coffee liqueur to the crumble topping on Conchi's apple tart. The local cooperative sells wine from the Somontano denomination at €4 a bottle, produced by families who can trace their vine-growing lineage back to the Reconquista. British visitors expecting Rioja prices will be pleasantly shocked: here, excellent wine costs less than bottled water.

Morning brings the real agricultural theatre. At 6:30am, tractors cough into life and head for the fields, their drivers carrying thermoses of coffee strong enough to etch steel. During harvest season – late June for wheat, September for almonds – the village air fills with dust and the smell of freshly cut grain. It's not romantic, but it is authentic, and visitors who rise early enough can follow the farm tracks on foot or bicycle, provided they remember to close every gate behind them.

Between Two Worlds

Olvena occupies that sweet spot where the Ebro Valley meets the first folds of the Pre-Pyrenees. Drive fifteen minutes south and you're among vast vineyards and modern bodegas. Head north and the road climbs into proper mountain country, where griffon vultures circle over limestone cliffs and the village of Alquézar attracts coachloads of Spanish schoolchildren to its medieval streets.

This positioning makes Olvena an excellent base, provided you have wheels. Barbastro, ten minutes away, offers supermarkets, pharmacies and the magnificent 16th-century cathedral that somehow survived the Civil War intact. The Vero River canyon, twenty minutes distant, provides swimming holes deep enough to cope with August's forty-degree heat. But Olvena itself? It shuts down completely between 2pm and 5pm, and the nearest cash machine sits fifteen kilometres away in Salas Altas.

Winter brings a different kind of isolation. When the cierzo really gets going, it can hit 100 kilometres per hour, rattling windows and stripping paint from south-facing walls. Snow falls perhaps once every three years, but when it does, the road from the main highway becomes impassable within hours. The village shop – really just a room in someone's house – stocks basics like tinned tomatoes and toilet paper, but you'd better like the brand they've got because it's that or nothing.

The Return Journey

Most visitors stay two hours, just long enough for coffee and a lap of the village streets. They photograph the church, buy a bottle of Somontano red from the honesty box outside number 47, and depart for somewhere with more obvious attractions. This isn't wrong – Olvena makes no pretence of being a destination. What it offers instead is context: a place to understand how most of rural Spain actually functions when the tour buses aren't looking.

The British obsession with "authentic" travel experiences often sends people to cooking classes in Barcelona or flamenco shows in Seville. Olvena provides something subtler: the chance to sit in a bar where the television plays local news nobody watches, where the barman's grandson does homework at a corner table, where your coffee comes with a free lecture on why English people can't make proper bread. It's not comfortable, exactly, but it's real.

Leave by the same road you arrived on, past the cemetery where every grave carries fresh flowers and the names read like a Spanish history book: Pilar, Vicente, Rosario, Francisco. The cereal fields stretch away on both sides, and if you visit in late June, you'll see combine harvesters working in formation, throwing up clouds of chaff that catch the sunlight like gold dust. Somewhere in the village, the church bell will strike the hour, and three people will pause whatever they're doing to count the chimes, just as their parents did, and their parents before them.

Olvena doesn't need you to visit. It was here before you arrived and it'll be here long after you've gone, measuring time not in tourist seasons but in harvests, in generations, in the slow patient rhythm of people who know exactly who they are and where they belong.