Full Article

about Alaior

Inland Menorca municipality with a strong university and cheese-making tradition; known for its archaeological sites and medieval old town.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The 13:05 bus from Mahón drops you at a roundabout scented with wild rosemary. Within five minutes you’re climbing Carrer de Sa Roca, past yoghurt-coloured houses whose shutters open like eyelids, and you realise the soundtrack has changed. No club beats, no cocktail shakers, just a scooter echoing off stone and the clink of coffee cups in Bar 4 Camins. Alaior doesn’t hush for visitors; it simply carries on.

Built on Milk and Stone

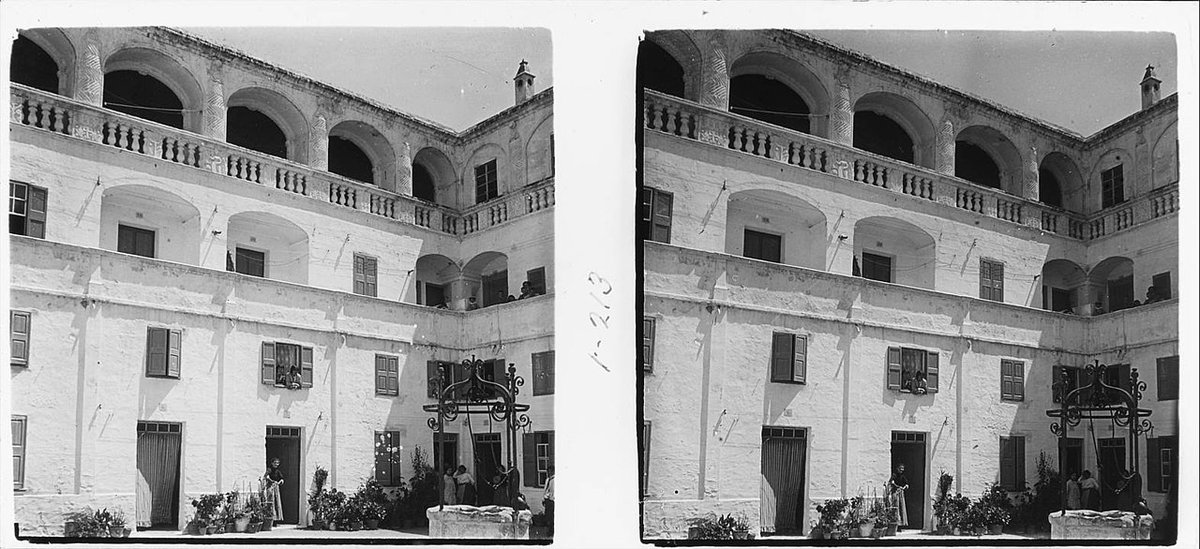

At 130 m above sea level the town rides a gentle hill that once guided ships with its silhouette. The climb is short but steep enough to make British calves notice the second glass of Rioja later. Grey limestone walls, hacked out of neighbouring quarries, give the place a uniformity that feels sturdy rather than pretty. Generations of dairy farmers have folded that same stone into terrace walls so the cows could graze the thin topsoil. Their reward is the island’s only Protected Designation of Origin cheese: Mahón-Menorca, produced in cooperatives on the outskirts and aged in cloth-lined caves that smell of butter and sea salt.

Pop into the little cheese museum (free, tip jar on the counter) before 13:00 or you’ll meet a locked door and a shrug that says “torna demà”. Exhibits are labelled in Catalan and English, and the staff will hand you a sliver of semi-curado that tastes like a milder coastal cousin of cheddar. Buy a wheel in the market hall on Friday morning and the vendor will vacuum-pack it so it survives the cabin-baggage dash to Luton.

When the Church Bell Means It

Santa Eulàlia’s sandstone tower rises from the highest point, visible long before you reach the centre. Inside, baroque altarpieces gleam with the kind of gilt Spain does so well, but the real draw is timing your visit with Saturday-evening vespers. The 18th-century organ growls awake, filling the nave with chords that make even agnostics pause. Climb the spiral stair to the roof (€8, cash only, summer only) and you’ll see two coastlines at once: the south’s scalloped coves and the north’s darker, cliff-lined horizon. Tickets are sold at a side door that looks permanently shut; persist.

Round the corner the town’s civil-war air-raid shelter tunnels under the old convent. A volunteer will hand you a hard hat and tell you in rapid Spanish how Franco's planes strafed the market. The ceiling is low; anyone over six foot spends the tour bent like a question mark.

A Coast that Answers to the Wind

Alaior owns 12 km of shoreline, but none of it sits beside the town. Instead you descend winding lanes that suddenly reveal Cala en Porter, a beach wedged between ochre cliffs. The sand is coarse, the entry steep, and the swell can dump you without warning, yet families return year after year because the lifeguards are vigilant and the pedalos come with shade canopies. Ten minutes west lies Son Bou, the island’s longest stretch—2 km of pale gold backed by wetlands loud with reed warblers. A wooden walkway steers you past the nudist zone (clearly signed, so no awkward missteps) to a bar that sells Estrella at airport prices. Bring coins for the showers: €1 for three minutes, cold only.

When the tramuntana blows from the north both beaches chop up. Locals simply swap sides; head to the southern corner of Son Bou where the headland blocks the breeze, or drive 20 minutes to the sheltered inlet of Cala Mesquida. The bus timetable doesn’t cater to such meteorological fickleness, so car hire or a stout pair of lungs is useful.

Walking Off the Cheese

The Camí de Cavalls, Menorca’s 185 km medieval bridleway, cuts through municipal limits. From Alaior you can join at Cala en Porter and hike east to Binigaus beach, a 90-minute tramp that alternates between holm-oak shade and limestone glare. Stone way-markers appear every kilometre, but mobile coverage is patchy—download the route before you leave the hotel Wi-Fi. In July the heat can top 35 °C by 11 a.m.; carry more water than you think civilised and a floppy hat that makes you look like your aunt on a cruise. Spring brings colour—wild gladioli, poppies the exact shade of a Royal Mail pillar box—and the scent of fennel crushed underfoot.

Eating After the Siesta

Mid-afternoon Alaior folds in on itself. Shutters clatter, the chemist pulls down its blind, and even the dogs look horizontal. Plan lunch for 15:30 or wait until 20:00 when the streets wake hungry. The cheeseburger at Es Moli de Foc slips a disc of semi-curado under the bun, delivering a salty umami punch that converts the sceptical. Vegetarians fare better at Sa Sinia, where artichokes arrive braised in mint and lemon, a dish bright enough to cut through August humidity. Pudding is almost always gelato: Italian families emigrated here in the 1950s and their descendants still run two parlours on Carrer del Ramal. A two-scoop cone costs €2.80, cash only, and the pistachio tastes like the nut’s green heart.

Fiesta, Noise and Horse Sweat

August’s Sant Llorenç fiesta turns the grid of quiet lanes into a weekend rave with confetti cannons and gin stalls. The highlight is the jaleo—riders on Menorcan horses coax the animals to rear on their hind legs while the crowd ducks under the hooves. British health-and-safety officers would reach for the smelling salts; here toddlers sit on parents’ shoulders for a better view. Earplugs advised: brass bands march until 04:00. September’s Mare de Déu de Gràcia is smaller, more equine, and ends with a communal paella in the main square. Visitors are welcome to queue for a plate; bring your own spoon and expect to share a table with a grandmother who speaks no English yet insists you try her homemade fig liqueur.

Getting Here, Getting Out

Bus L1 from Mahón runs every half hour Monday to Saturday, hourly Sundays, and deposits you at the edge of the old quarter in 20 minutes. A single costs €1.25—have the exact coin or the driver keeps the change. Taxis from the airport are a flat €24; book the return journey early in August because every cab is spoken for by 18:00. If you hire a car, fill up before returning it—petrol stations on the island close earlier than British supermarkets and won’t reopen for a lone stray Renault.

Parking outside the historic core is free and signed; electric chargers sit beside the sports centre. Ignore the temptation to squeeze into the old town—lanes narrow to the width of a Yorkshire terrace and the locals in battered Seats have right of way plus the paintwork to prove it.

Worth the Detour?

Alaior will never outrank neighbouring Mahón on the souvenir tea-towel circuit, and that suits the 9,000 residents fine. Come for the cheese, stay for the evening light that turns the stone walls honey-gold, and leave before you start expecting a gift shop on every corner. Bring comfortable shoes, a tolerance for irregular opening hours, and enough Spanish to say “un café amb llet, si us plau”. You won’t tick off blockbuster sights, but you will remember how a town feels when tourism is the side dish, not the main course.