Full Article

about Ariany

Small hilltop town with sweeping views over the Pla; known for its quiet and traditional rural architecture.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell strikes eleven and the only reply is a tractor grinding through barley stubble somewhere beyond the sandstone houses. In Ariany, population 842, the loudest sound is often your own footsteps on the short, pale streets that climb to a modest plaza and the seventeenth-century Nativitat church. No souvenir stalls, no piped music, no coach parks: just the smell of warm bread drifting from the mini-market and a handful of elderly residents trading gossip under the plane trees.

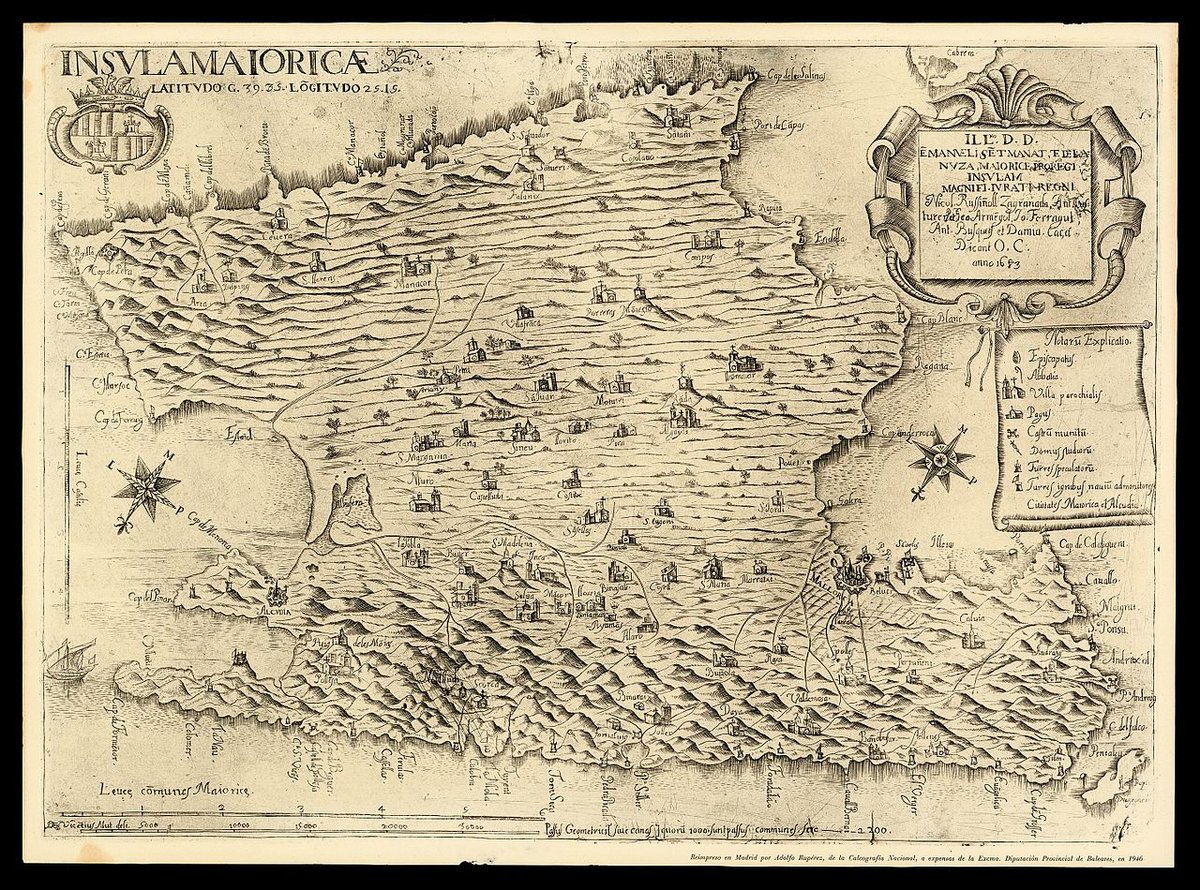

This is the Mallorca that rarely makes the brochures. Forty-five minutes' drive north-east from Palma airport, the Ma-3240 peels off the main Artà road and rises gently onto the Pla, the island's grain belt. Wheat, almonds and a patchwork of dry-stone walls stretch to every horizon; the Tramuntana mountains shimmer to the west and, on very clear winter days, you can pick out the lighthouse at Cap de Formentor. Ariany sits almost exactly at the geographical centre of the island, a fact that seems to please locals more than any architectural flourish.

What you see is what has always been here: a fortified hill-top hamlet that grew around farming, not tourism. The church façade is plain, almost severe, but step inside when the doors are unlocked (mornings before noon, evenings after six) and you'll find a gilded Baroque altarpiece paid for by wheat profits three centuries ago. Look closer at the houses edging the narrow lanes and you'll spot carved date stones – 1694, 1721, 1787 – and heavy arched doorways built wide enough for a mule cart. Nothing is staged; paint peels, geraniums spill from cracked terracotta, and the town's single public telephone still hangs on a wall opposite the chemist.

British cyclists know the place mainly as a feed stop on the Mallorca 312 sportive. They freewheel in, grab a coke at Bar Can Jordi and roll on towards Petra, rarely pausing long enough to notice the stone coat of arms above the bar door. That's a pity, because Ariany rewards the slower traveller. On Thursdays the square fills with six or seven market stalls: pyramids of oranges, rope-handled baskets, cheap socks, a van that will sharpen your kitchen knives while you wait. Housewives compare cucumbers in rapid Mallorquín, schoolchildren dart between the crates, and for two hours the village feels positively bustling. Come Friday, silence returns.

Walking is the best, indeed almost the only, organised activity. A level rural track heads north to Petra (5 km) past a derelict windmill; southbound lanes dip through almond groves towards Santa Margalida. You will meet more sheep than people. If the day is windy – and the Pla can funnel a fierce breeze – dust drifts across the path and the fields hiss like dry rain. Summer midday hikes are foolish; start early, carry water, and remember there is no shade until the next hamlet. Spring is kinder: green wheat trembles like a calm sea, stone walls warm in soft light, and the air carries the faint sweetness of blossom.

Food is simple, local and erratically served. Bar Can Jordi offers toasted sobrassada sandwiches, tortilla the size of a cartwheel and chips that arrive in a paper-lined basket. Prices hover around €8–12 for a plate; cash only, and the owner may close early if custom is thin. Ses Torres, at the far end of the main street, lays on a weekday lunch buffet of roast chicken, salads and rice – popular with council workers and handy for families who blanch at the thought of octopus. The only alternative is Pizzeriany, open weekends March to October, where a thin-crust margherita costs €9 and you can sit on the roof terrace watching swifts race the sunset. Do not expect dinner: by 21:00 most ovens are cold and the square is lit only by the orange glow of street lamps.

Practicalities matter here. The village has no cash machine; the nearest is six kilometres away in Petra. Bring euros, or face an unplanned cycle ride. There is no petrol station, no pharmacy on Sundays, and the mini-shop shuts for siesta (14:00–17:00). Parking is free and usually easy on Calle de l'Església, but keep wheels off the pavements – they are barely a metre wide and locals walk in the roadway without hesitation. Public transport exists in theory: a twice-daily bus from Palma, changing at Sineu, that deposits you at 13:30 and picks up again at 17:15. Hire a car; the drive is straightforward and you'll need wheels to reach an evening restaurant unless you fancy tinned tuna in your holiday let.

Accommodation is limited to a handful of agroturismos in the surrounding fields. Most are converted farmhouses with salt-water pools, beams thick as ship timbers and breakfast tables laden with ensaïmada, the spiral lard pastry that Mallorcans eat for breakfast. Expect to pay €120–€160 a night for a double, including VAT, more during May half-term when British cycling clubs block-book rooms. Check whether dinner is offered; otherwise you face a 15-minute night drive to Petra or Manacor for anything more ambitious than crisps and a nightcap.

Evenings are startlingly quiet. Swallows give way to bats, the church bell counts the hours, and the sky – unpolluted by neon – spills into starlight. You may hear a distant dog, a clank of farm gates, the whisper of a television through an open shutter. It is the sort of silence that makes city dwellers nervous until they learn to match its rhythm.

Ariany will never compete with Deià's galleries or Pollença's Sunday market. That is precisely its point. Come for half a day en route to the east-coast coves, or base yourself here and radiate out to the pottery workshops of Pòrtol, the Wednesday market at Sineu, the talayotic ruins at Son Fornés. Use it as a breathing space between flights and beach towels. Just do not arrive expecting postcard perfection; the village is handsome in a workmanlike way, proud of its grain-store past and indifferent to Instagram. If that sounds appealing, park under the plane trees, order a café amb llet and watch the Pla unfold in shades of gold. The tractor will still be grinding when you leave, and Ariany will settle back into its low, steady heartbeat, exactly as it has done for four hundred years.