Full Article

about Petra

Birthplace of Fray Junípero Serra; historic town with cobbled streets and a quiet inland atmosphere.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

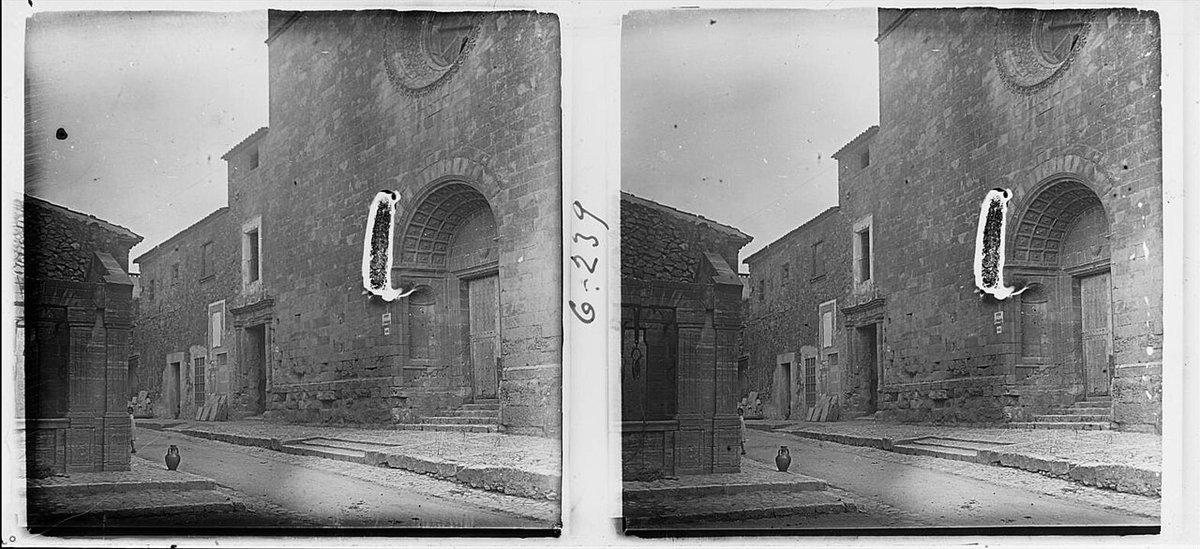

The stone façade of the Convent de Sant Bernadino turns honey-gold at precisely 4:47 pm on late-autumn afternoons. That's when the sun clears the church tower and hits the sandstone cloister, transforming what looks like any other provincial religious building into something that momentarily justifies Petra's existence on tourist maps. The effect lasts twelve minutes. Then it's just another quiet square where cats stretch across warm flagstones and elderly residents judge the parking skills of day-trippers.

This is Petra's secret: it's spectacularly unspectacular. While the rest of Mallorca competes for Instagram glory, this central-plains town of 3,000 souls specialises in the art of not trying too hard. The almond groves stretch to the horizon. Dry-stone walls divide fields with agricultural precision rather than aesthetic consideration. Life proceeds at the pace of agricultural necessity, not tourism spreadsheets.

The Franciscan Who Conquered California

The single-room museum occupying Junípero Serra's 1713 birthplace won't overwhelm anyone. Display cases hold yellowing documents, a rough wool habit, and maps showing the nine missions the Franciscan founded along what's now the US West Coast. Americans—particularly Californians—treat the place with reverential whispers. Everyone else tends to glance at their watches after ten minutes, wondering if this constitutes the town's highlight.

It doesn't. Petra's appeal lies in what happens after the museum, when visitors drift into the web of narrow lanes radiating from Plaça Ramon Llull. Here, honey-coloured mansions built from local marès stone incorporate Gothic arches with 19th-century bourgeois additions. Patios visible through wrought-iron gates reveal climbing bougainvillea and the occasional vintage Seat 600 parked beside citrus trees. Nobody's renovated these houses for foreign buyers. They simply maintained them, generation after generation, creating an architectural continuity that's become increasingly rare on an island where every other village seems to have discovered the lucrative appeal of boutique hotels.

The Església de Sant Pere dominates the skyline with its late-Gothic nave and baroque retablos. Inside, the air carries that particular European church smell: incense, beeswax, and centuries of stone absorbing human hopes. The building's scale seems disproportionate to the town's size until you remember that Petra once served as the region's religious centre, collecting tithes from surrounding farmsteads wealthy enough to fund ecclesiastical ambition.

Walking Into Nothing (Which Is the Point)

Leave the town centre in any direction and you'll hit the pla—Mallorca's flat interior plain. This isn't dramatic mountain hiking country. It's agricultural infrastructure: dry-stone walls creating geometric patterns, century-old olive trees with gnarled trunks, the occasional stone windmill converted into storage rather than romantic accommodation. Paths to Ariany or Santa Margalida follow farm tracks wide enough for tractors. Signage exists but assumes basic directional competence.

Spring transforms these routes into Mallorca's most convincing imitation of Tuscany. Almond blossom creates clouds of white petals that drift across the path like agricultural snow. Wild fennel and rosemary scent the air. The only sounds: distant dogs, the mechanical whirr of irrigation pumps, your own footsteps on gravel. It's walking stripped back to essentials—no gift shops, no viewpoint cafés, just landscape and the rhythm of your own movement.

Summer renders the same routes potentially hazardous. Temperatures regularly hit 38°C, shade is non-existent, and the agricultural machinery kicks up dust that hangs in the air like fine flour. Locals schedule any necessary movement for dawn or dusk. Midday activity is reserved for mad dogs and English hikers who didn't read the climate section of their guidebooks.

The Restaurant Timetable That Rules Everything

Petra's restaurants operate on agricultural time, not British holiday schedules. Kitchens open at 1 pm for lunch and close around 4 pm. They reopen at 8 pm for dinner. Arrive at 3:45 pm and you'll receive sympathetic smiles plus directions to the bakery. Arrive at 6 pm expecting anything beyond coffee and you'll encounter closed doors and confusion about why anyone would be hungry at this peculiar hour.

Es Celler de Petra serves proper Mallorcan country food: roast lamb falling off the bone, tumbet (the island's superior answer to ratatouille), and verdura de temporada that tastes like vegetables remember tasting before supermarkets standardised flavour into uniform blandness. The three-course menú del día costs €14 and includes wine produced within ten kilometres of your table. The English menu contains endearing translations—"lamb with crashed potatoes"—but the staff navigate dietary requirements with rural practicality: "No gluten? Fine, we give you meat and vegetables. Problem solved."

Forn de Plaça opens at 6 am to supply farmers with coffee and ensaïmades before they head to fields. By 10 am it's transformed into social centre where retired men solve agricultural policy over small glasses of cognac. Their gató—almond cake made with local nuts and minimal sugar—pairs perfectly with afternoon coffee for those who've adjusted to Spanish eating rhythms.

When to Come, When to Stay Away

Wednesday morning brings the weekly market. Farmers from surrounding fincas arrive with produce that never sees supermarket shelves: tomatoes selected for flavour rather than transport durability, onions still carrying field soil, lemons with actual scent. The market occupies two streets and finishes by 1 pm, after which Petra reverts to its default setting of agricultural quiet.

Late June's Sant Pere festival involves processions, fireworks, and residents who've moved to Palma returning to compete in paella contests. August's Sant Bernat celebration is smaller but includes the traditional correfoc—devils running through streets with fireworks—which British health and safety officials would find deeply troubling. November's Junípero Serra commemoration attracts American academics and bemused locals who can't quite believe anyone travels this far to honour a monk who left 300 years ago.

Winter reveals Petra's most authentic face. Agricultural work continues regardless of tourism seasons. Bars fill with men discussing rainfall statistics and almond prices. The museum operates reduced hours. Some restaurants close entirely while owners visit relatives on the mainland. Visitors willing to embrace short days and cool evenings discover a town existing entirely for itself, offering that increasingly rare experience: seeing a place that would continue being itself even if every tourist failed to arrive tomorrow.

The car park behind the Repsol station stays half-empty. The stone walls maintain their patient vigil. And for twelve minutes on late-autumn afternoons, the convent walls still turn honey-gold, whether anyone's watching or not.