Full Article

about Banyalbufar

Picturesque coastal village known for its stepped terraces that drop to the sea and its malvasía wine.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The terraces start before you’ve even parked. Dry-stone walls clamped into the slope like rows of ancient teeth, each one cradling a strip of vineyard that tilts toward the Mediterranean until it meets nothing but air. From the roadside lay-by above Banyalbufar you can read the whole story: every metre of land was fought for, levered into place, then coaxed for eight centuries to grow a grape the Arabs called “the perfumed one”.

That grape is still here. Malvasía vines, low and wind-battered, share the terraces with wild fennel and the odd lemon tree. The wine they yield is bottled locally and sold for about €11 in the village bodega; open it back in your apartment in Palma and the glass smells almost exactly like the breeze that slid past you on the mirador – salt, bruised herbs, something faintly honeyed. It is the cheapest souvenir that still weighs nothing in your suitcase.

Walking downhill through five centuries

The village itself is a single lane that corkscrews down to the sea. Houses are mortared in the same honey-coloured stone as the terraces, so from a distance the settlement looks like an extension of the agriculture rather than an interruption. Park in the free lot on the western edge – spaces are generous before ten, impossible after twelve – and walk. The first landmark is the Torre de Ses Ànimes, a sixteenth-century watchtower built to spot Ottoman pirates. Climb the spiral; the wooden steps creak like an old galleon. From the roof you can see the road you arrived on, ribbon-thin and already toy-like, while below the water turns from tourmaline to slate depending on the cloud shadow. Sunsets here are absurdly cinematic, but arrive thirty minutes early or you’ll be sharing the ledge with two coach-loads of German cyclists.

Back at street level the church of La Natividad squats over a pocket-sized plaça. Its doorway is Gothic, the bell-tower is Baroque, the interior smells of candle wax and wet stone. Mass is at 19:00 on Saturdays; visitors are welcome but the priest delivers in rapid Mallorquín, so unless your Catalan is holiday-grade you may simply sit at the back and enjoy the echo.

The only supermarket is a room no bigger than a village post office, stocking UHT milk, tinned lentils and the local sun-dried tomatoes that taste of iron and August. If you need oat milk, kale or anything gluten-free, buy it in Esporles on the drive up. Banyalbufar shuts early and shuts thoroughly.

A beach that makes you earn it

Cala Banyalbufar is a ten-minute descent on a paved path that feels gentle until the return journey. The beach is pure pebble – no sand, no mercy – so bring rubber shoes or embrace the hobble. The stones are smooth and warm, the water clears to snorkel-depth within metres, and on weekdays you’ll share the cove with perhaps a dozen locals and the odd goat that has wandered down for salt. There is no snack bar, no sun-lounger hire, no lifeguard. What you carry down you must carry up, including your rubbish. The climb back averages twenty minutes if you’re fit, thirty-five if you stopped for a second bottle of malvasía at lunch. Factor that into your evening plans.

When the mountain meets the sea

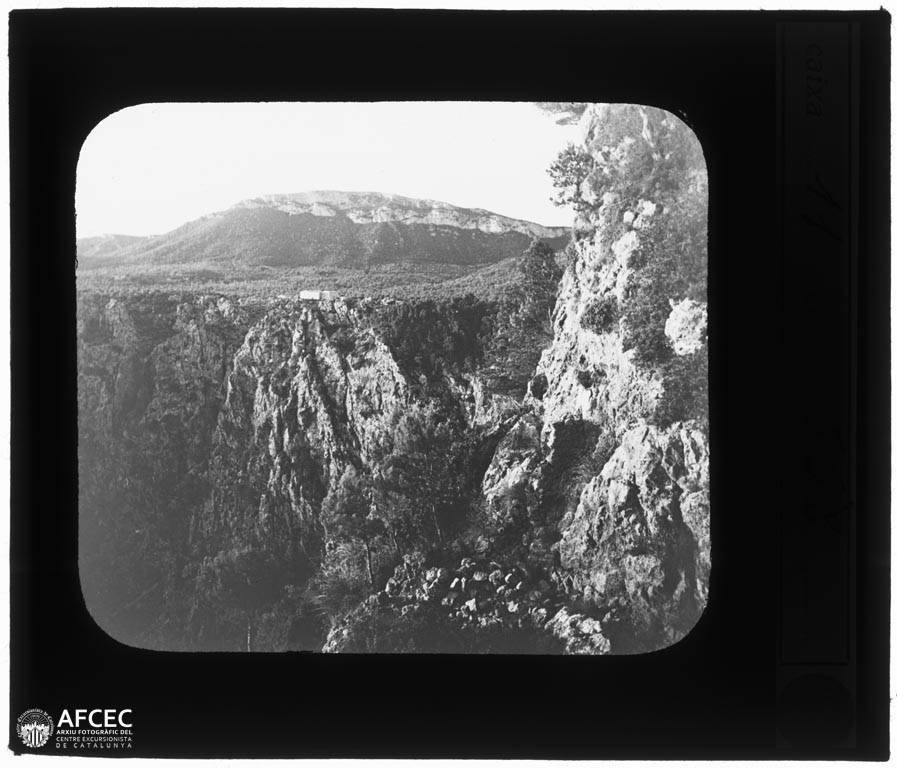

Behind the village the Serra de Tramuntana rises sharply to 942 m within six kilometres. A web of cobbled mule paths – the old dry-stone drainage system still visible underneath – threads through holm oak and rosemary. The shortest outing is the Camí de s’Arxiduc, a contouring track built in the 1860s so the Austrian archduke could ride without getting his boots dusty. Allow ninety minutes round-trip from the church; you’ll gain enough height to look back on the terraces as a green staircase dropping into blue. Spring brings poppies and the smell of wild thyme; August brings 35 °C and precious little shade. Start early or finish late – the same rule the farmers use.

Serious walkers can continue west along the GR-221 to Port des Canonge, a hamlet with a tiny shingle cove and a bar that opens only at weekends. The full stretch is 12 km with 700 m of cumulative ascent; carry two litres of water per person because fountains are seasonal and the limestone reflects heat like a mirror.

What to eat when the day folds into evening

There are four restaurants, all within two minutes of each other. Es Vergeret has the widest terrace and serves a credible fish paella for two at €36; ask for the “senyoret” version if you dislike extracting prawns from their shells. Sa Fonda majors on roast lamb shoulder, slow-cooked until it collapses into its own puddle of potato and onion. Vegetarians get aubergine layered with local goat cheese – mild, almost buttery, nothing like the chalky logs sold in British farmers’ markets. Wine lists are short and mallorquin-centred; the house malvasía is usually the same price as still water.

Pudding choices are limited to almond cake or almond ice-cream, both worth it if only to understand why the island once exported marzipan to Venice. Coffee comes in small glasses and without milk unless you plead. Tipping is casual: round up to the nearest five or leave a euro per person if service was actually smiled at.

The things that don’t make the postcards

Mobile reception flickers between one bar and none; download offline maps before you set out. The village has no cash machine and many places won’t accept cards for bills under €20. Parking tickets are enforced with Germanic efficiency – display the blue disk even if you’re “just nipping” to the tower. Finally, coach parties arrive around 11:30 and depart at 16:00; if you hear English being spoken in the bakery you’ve probably hit the rush. Either stay overnight (there are two small hotels and a handful of legal rentals) or plan to be somewhere else during those hours.

Leave before dark and you’ll descend the Ma-10 with the sun firing straight into your windscreen, the terraces turning bronze, the sea below already ink-blue. Somewhere on the radio a woman sings in mallorquín about leaving and returning. You won’t understand the words, but the tune matches the gradient: slow, winding, and suddenly over.