Full Article

about Santa María de Guía

Historic town known for its Queso de Flor; its old quarter is a listed historic-artistic site and it has the Cenobio de Valerón.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The Knife-Maker's Morning

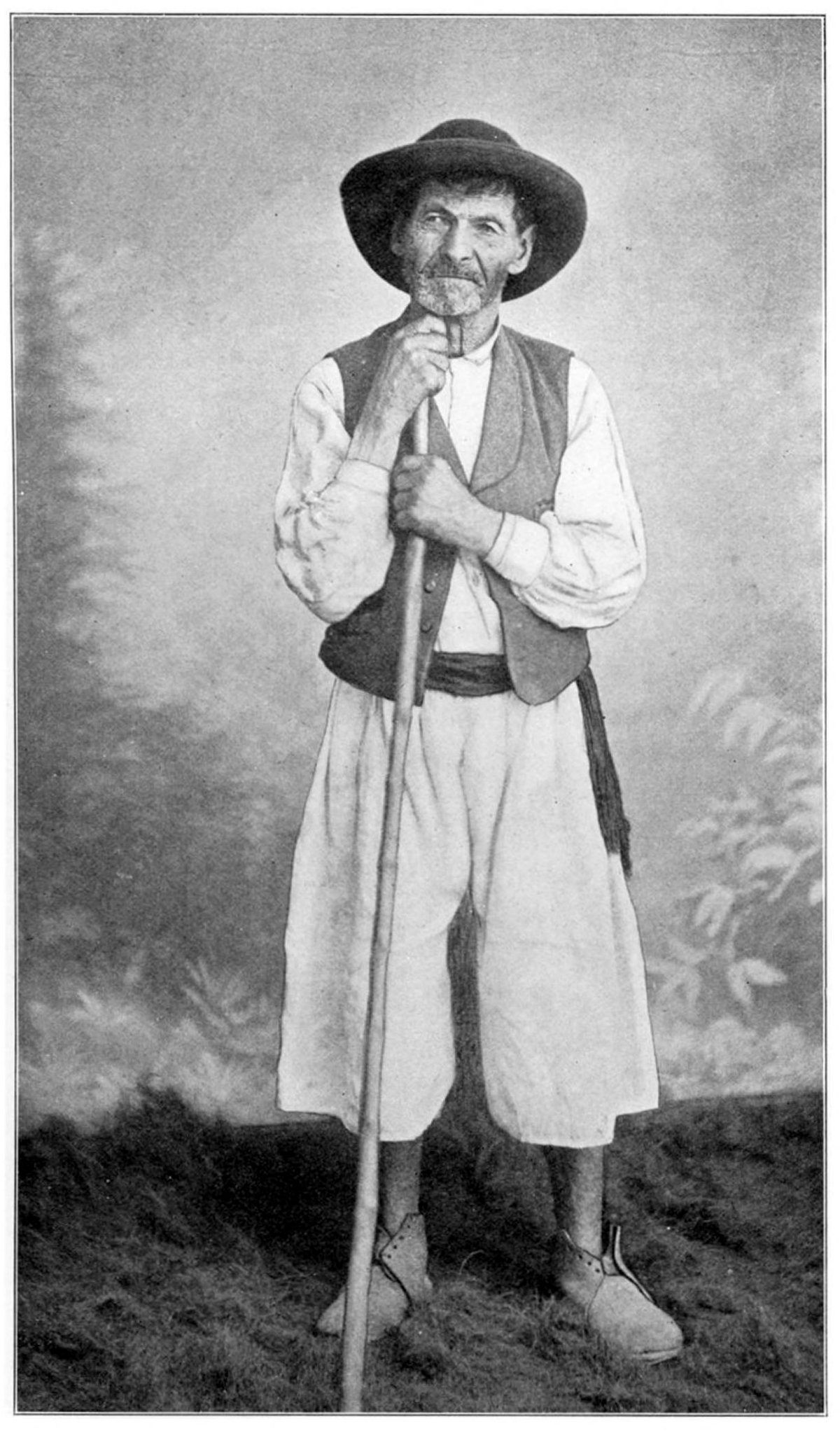

By nine o'clock, the forge is already glowing. In a workshop no wider than a London allotment shed, a third-generation cuchillero hammers steel against volcanic stone. Each Tuesday and Thursday, visitors can watch—provided they arrive quietly, stand clear of the anvil, and don't mind the occasional shower of sparks. It's this unshowy authenticity that defines Santa María de Guía, a market town of 14,000 souls clinging to Gran Canaria's northern escarpment.

The place doesn't announce itself. From the GC-2 motorway, you spot a cluster of ochre roofs between banana plantations and think "another Spanish village." Then the road climbs 250 metres through eucalyptus-scented air, and suddenly you're threading between stone houses so close you could shake hands with someone leaning from the opposite balcony. Parking spaces appear on the ring-road—take one immediately because the streets ahead narrow to pram-width and Google Maps lies about driving times.

A Quarter Hour from the Atlantic

Despite sitting inland, Guía's relationship with the sea runs deep. Fishermen's families have climbed these same cobbles for four centuries, carrying today's catch to market before the asphalt existed. The Atlantic lies just eight kilometres north—close enough that salt spray sometimes drifts over the ridge on westerly winds. Local restaurants (there are six, plus two bars serving food) receive dorada and vieja still flapping in plastic crates, delivered by van at lunch service.

The beach at nearby San Felipe offers black volcanic sand and proper waves—none of your imported Sahara dust. It's wild enough that Red Flags fly regularly, but perfect for a bracing walk after cheese-tasting. Locals claim the water stays swimmable year-round; British constitutions might disagree from November through March when the mercury dips to 18°C.

The Cheese That Flowers

Queso de flor isn't a marketing gimmick—it's geography you can taste. Guía's upland pastures sit above the marine layer, where Atlantic moisture meets volcanic soil, producing thistles whose purple flowers become vegetable rennet. The result: a semi-soft goat cheese with the gentle tang of artichoke and a texture somewhere between Wensleydale and young Manchego. Production follows the thistle bloom, meaning supplies dwindle by late summer and disappear entirely some years.

The Fiesta del Queso de Flor (usually first weekend in May) turns the main plaza into an open-air dairy. Producers set up trestle tables beneath jacarandas, offering matchbox-sized samples alongside glasses of dry Canarian white. Arrive before 11 a.m.—by midday Spanish families have queued twice round the square and the best wheels are wrapped in newspaper heading home.

Wednesday market operates year-round, smaller but more reliable for visitors. Look for Esther's stall beside the 16th-century church—she speaks enough English to explain why her cheese costs €24 a kilo (answer: thirteen goats, hand-milked twice daily, thistles gathered at dawn). Bring cash; the card machine "se rompió" months ago.

Walking Through Five Centuries

Guía's historic quarter earned National Monument status in 1985, though nobody's polished it for tourists. Stone doorways still bear the original family crests—look for the dolphin carved above number 14 Calle Real, marking a 17th-century merchant's house. The Church of Santa María occupies its own plaza where elderly men play dominoes beneath Indian laurels; inside, woodcarvings by local boy José Luján Pérez demonstrate why he became the Canaries' most celebrated imaginer.

From the church, lanes radiate like spokes. Calle La Paz climbs past balconied houses painted Pompeii red and sunflower yellow—colours derived from local ochres that never fade. Five minutes uphill brings you to the Mirador del Conde, a volcanic-stone balcony overlooking banana plantations that stretch to the sea. On clear days, Tenerife's Mount Teide floats on the horizon like a snow-capped mirage.

The signed Ruta de los Molinos loops three kilometres through former grain country. You'll pass two water mills restored to working order and four windmills missing their sails—victims of 1950s mechanisation. The path's steeper than tourist-office leaflets suggest; decent footwear essential. Midway, a stone bench faces west across the Barranco de Santa María—perfect spot for the cheese sandwich you bought at the market.

When to Come, When to Stay Away

Spring brings wild marigolds to the ridge and temperatures hovering round 22°C—ideal for walking without the sweat factor. Autumn matches this climate-wise but adds grape harvest in the lower valleys; local wineries offer tastings that rarely appear in guidebooks. Summer stays cooler than the southern resorts thanks to 300-metre altitude, though midday walking becomes masochistic. Winter means occasional rain and cloud rolling off the Atlantic—atmospheric for photography, less so for mountain views.

Avoid August if possible. The fiesta patronal packs the town with returning Canarians, hotel prices spike in Las Palmas, and you'll queue twenty minutes for coffee. Also dodge Monday mornings—everything's closed while shopkeepers recover from weekend visitors.

Practicalities Without the Pain

Getting here: Fly direct to Gran Canaria from most UK airports (4–4½ hours). Hire cars at the airport—pre-book in winter when northern Europeans escape their own weather. Take the GC-2 westbound, exit 15 signed "Santa María de Guía." The 35-minute drive includes a dramatic climb through agave-covered slopes. Public transport requires bus 103 from Las Palmas to Guía's edge, then a ten-minute uphill walk—fine if you're travelling light and patient.

Where to stay: Guía itself offers one boutique hotel (six rooms, €90-120) and two rural houses on the outskirts. Most visitors base themselves in Las Palmas' Vegueta district—20 minutes' drive but with restaurants open past 10 p.m. and proper pavements.

Eating: Restaurante La Cuchara de Juan serves goat stew that could revive the recently deceased—book ahead weekends. Cafetería Plaza offers reliable coffee and tortilla for breakfast from 8 a.m. (rare in these parts). For picnic supplies, Supermercado Guayarmina stocks local cheese wrapped in palm leaves, far superior to airport versions.

Money: ATMs exist on Plaza Mayor but frequently run dry on market days. Knife workshops and cheese stalls operate cash-only—bring euros or prepare for embarrassed apologies.

The Exit Strategy

Leave before the streetlights flicker on unless you've booked accommodation. These lanes weren't designed for night navigation, and the one-way system becomes a logic puzzle after dark. As you descend the GC-2, glance in the rear-view mirror—Guía's lights cling to the hillside like scattered embers, proof that places still exist where craftsmanship trumps commerce and the cheese has more character than most people you'll meet on the flight home.

Whether that justifies the detour depends on your tolerance for narrow streets and your suitcase capacity for dairy products. The knives, at least, travel well—just don't forget to pack them in the hold.