Full Article

about Voto

Manor houses and Trasmiera tradition

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell in San Vicente Mártir strikes eleven, and nobody stirs. Not because the village is empty—though at 2,800 souls spread across twenty-odd hamlets, it isn't exactly thronging—but because the cows across the road are still grazing, and in Voto the cattle set the tempo. One glance at the map explains why: the municipality is less a dot and more a green smear stretching from the A-8 down to the marshes of Santoña, a patchwork of meadows stitched together by lanes so narrow that two Fiats constitute a traffic jam.

This is Trasmiera country, the inland buffer between Santander's industry and the Atlantic surf beaches. British drivers fresh off the Santander ferry often barrel straight past on the motorway, bound for the Picos or the coast, which suits the locals fine. They have their own rhythm: milking at dawn, siesta when the sun climbs the valley walls, and a last stroll for the cattle at dusk. Visitors who synchronise with that beat discover there is more to see here than any single monument can deliver.

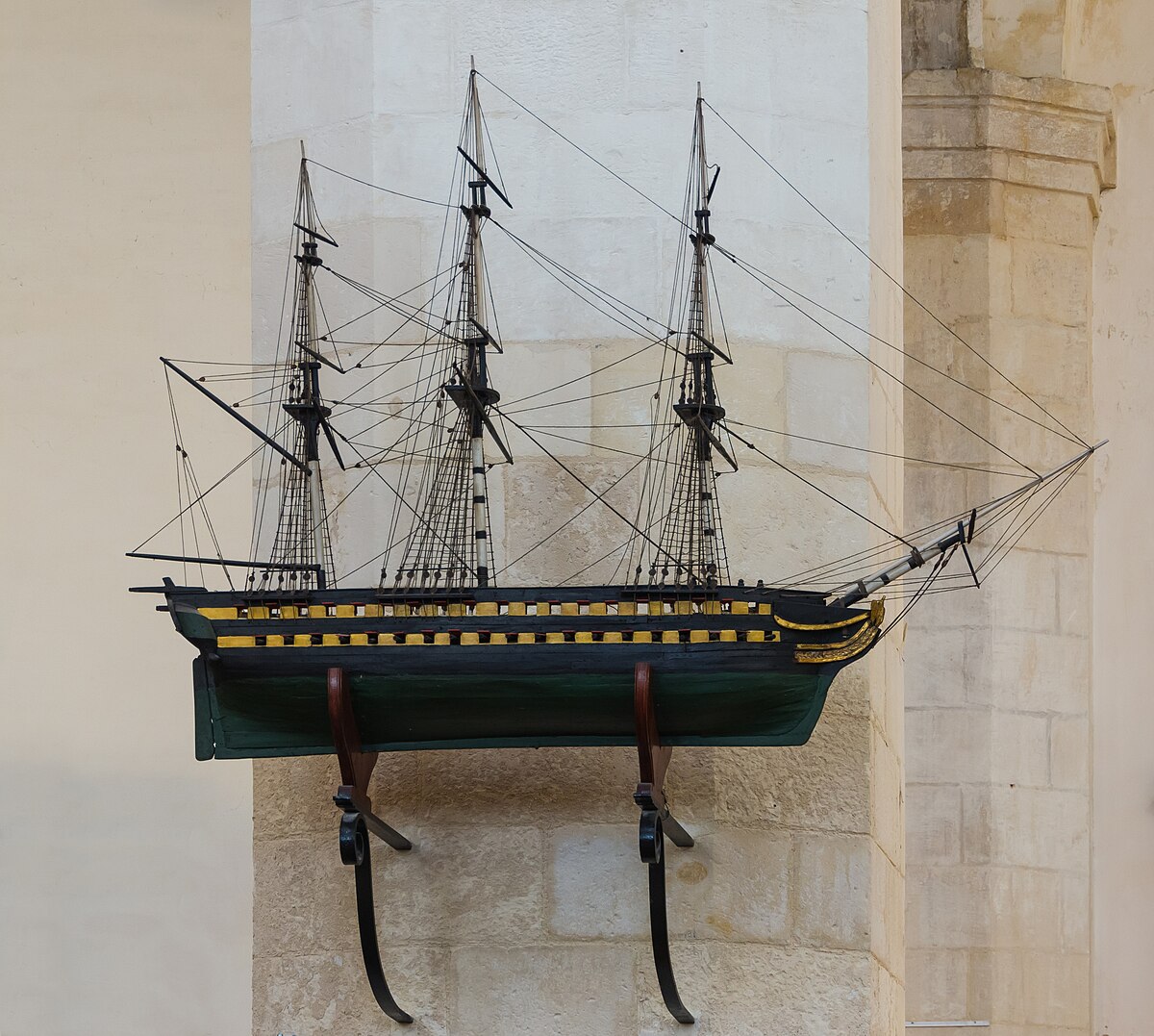

Start with the church itself, a sixteenth-century stone box whose plain façade hides an extraordinary baroque retablo inside. The caretaker keeps the key at the house with the green shutters opposite; ring twice and tip a euro. From the porch you can already spot the first of the region's trademark casonas montañesas—stone manor houses whose wooden balconies bulge out like ship prows. These aren't museum pieces; families still live in them, hanging washing beneath coats of arms carved while Elizabeth I was on the English throne. Walk fifty metres up the lane past the red dairy kiosk and the road dissolves into a dirt track that links Güemes to Helguera, two hamlets whose combined population wouldn't fill a double-decker bus. Between them lies the real attraction: pasture that glows emerald after rain, criss-crossed by dry-stone walls older than most countries.

Bring boots, not flip-flops. After a shower the clay sticks like digestives to a wool jumper, and Google Maps confidently sends hatchbacks down farm tracks that finish in a field. The classic circuit threads west from the main village through Bádames and Secadura, a 12-kilometre loop that passes three manor houses open to the public on random afternoons (knock anyway; the caretaker's dog will find you). Signposts are optional, but the Cantabrian version of a sat-nav is simpler: keep the cows on your left and the sea breeze—faint but perceptible—in your nostrils. Halfway round, the road climbs sharply enough for cyclists to consider pushing, then drops into a hollow where Nates church stands alone, its bells echoing off limestone scarps. Pause here and you will hear only birdsong and, if the wind shifts, the distant thud of surf on Playa de Berria twelve kilometres away.

That proximity to the coast is Voto's trump card. Drive twenty minutes north and the temperature falls five degrees; cow parsley gives way to salt spray and kite-surfers. The marshes of Santoña, Victoria and Joyel begin where Voto's fields end, a Ramsar wetland where spoonbills and migrating ospreys replace the herons of the meadows. On Sundays the road to the visitor centre clogs with Spanish families queueing for boat trips through the tidal channels, yet turn back inland and you can be the only car on the CA-147. The contrast is deliberate: coastal Cantabria sells seafood and selfies, Voto sells silence.

Silence, and cheese. The county's dairy co-operative collects milk twice daily, but a handful of farmers still make quesada and sobaos in farmhouse kitchens. Track them down by following the hand-painted signs that appear on barn doors: "Venta de Quesada, 2 km". One such operation runs out of a garage in Llerana; ring the bell and María Jesús appears in an apron, slicing still-warm cheesecake onto greaseproof paper. A palm-sized portion costs €2.50, tastes like lemony rice pudding, and travels better than any airport souvenir. She also sells whole milk in old Coca-Cola bottles—raw, unpasteurised, and illegal to import into the UK, so drink it there and then.

Evenings follow a predictable pattern. The single bar in the main village shuts its kitchen at nine sharp; arrive at nine-fifteen and you will be offered crisps and condolences. Better to book a self-catering cottage and cook yourself. Santander's hypermarkets stock everything from morcilla to monkish, but Voto's own Saturday morning market fits into a car park behind the church: two veg stalls, one van hawking chorizo, and a truck piled with knitwear. Buy the fabada beans; they are smaller than their Asturian cousins and cook in under an hour. Pair them with a bottle of sidra from the neighbouring valley—about €3.80, and the cork comes out with the same sigh you will make when the stars appear, unpolluted by streetlights.

Practicalities first, because guidebooks gloss over them. Public transport is theoretical: one bus leaves Santander at 07:35, returns at 14:00, and does not run in August when the driver holidays in Torremolinos. A hire car is essential; allow €35 a day from the ferry port, plus another €15 if you want sat-nav that recognises barrio names like El Pontarrón. Petrol is cheaper than Britain but motorway tolls nibble: the A-8 between Santander and Bilbao costs €9.50 each way. Withdraw cash before you arrive; the village ATM spends more time out of order than in, and the nearest alternative is a 15-minute drive to Colindres where the queue on pension day rivals post-office Britain circa 1978.

Accommodation options are thin. Finca El Mazo advertises wooden cabins with pool and games room; online reviews warn of indifferent management and curtains that do not close. An alternative is to stay on the coast at Laredo and commute—twenty-five minutes inland, but you lose the dawn chorus and the night sky. Better to rent one of the restored casonas through the regional tourist board; prices start at €90 per night for a two-bedroom house with oak beams and a bread oven you are welcome to light if you can remember the Scout manual.

Weather is a British topic, so treat Voto like the Lake District with better food. Spring brings daffodils in March, snow on the peaks till May, and meadows so lush you expect Heathcliff to stride past. Summer rarely tops 26 °C, yet the humidity feels warmer; afternoon thunderstorms crack like cannon over the valley. Autumn is the photographer's favourite—morning mist, russet oak, and migrating storks overhead—but also the season when lanes turn to porridge. Winter is serious: the pass to Liérganes closes at 600 m after the first snow, daylight shrinks to eight hours, and the only heating in many houses is a lareira, an open hearth that smokes back at you if the wind changes.

Leave time for the one experience that costs nothing. On a clear night walk five minutes beyond the last streetlamp, lie down on the stone wall opposite the dairy farm, and look up. The Milky Way appears with a clarity impossible anywhere south of the Pennines; satellites track across the sky, and occasionally the International Space Station flares like a torch. Nobody will disturb you—except perhaps the farmer's collie, who has learned that tourists carry biscuits.

Head back to Santander the quick way and you will reach the ferry in forty minutes, motorway hum replacing cowbells. Somewhere near the port a supermarket will sell identical sobaos in a plastic wrapper, stamped with a picture of a church that looks like Voto's but isn't. Buy them if you must; they taste of flour and regret. Better to keep the memory of María Jesús's cheesecake, the mud on your boots, and the realisation that Spain still has corners where the guidebook stars have not yet stuck their flags.