Full Article

about Guadalajara

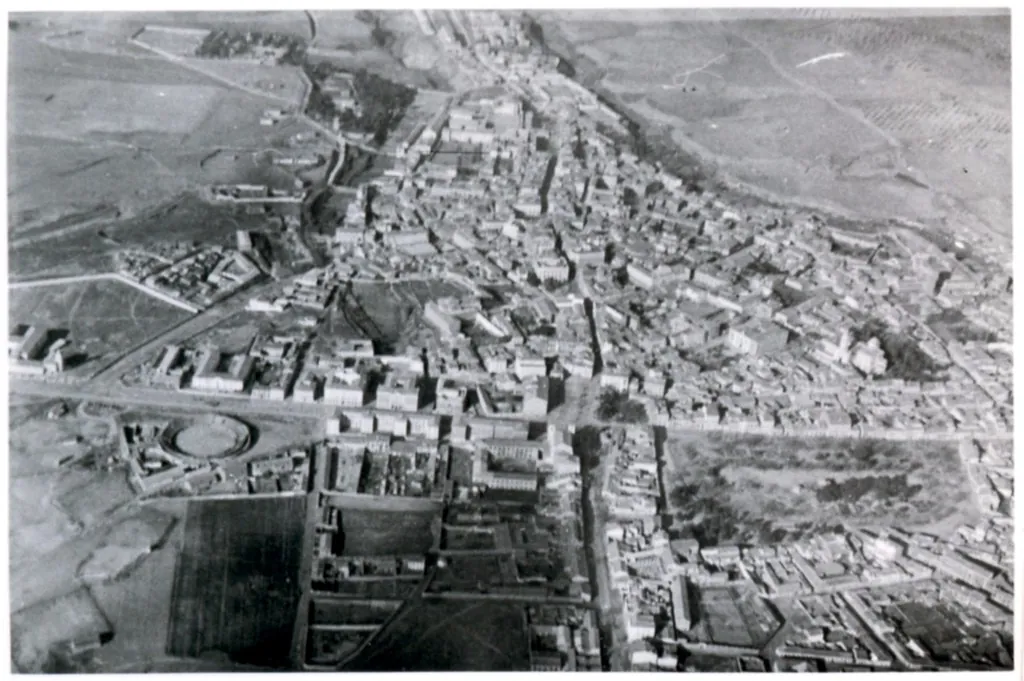

Provincial capital in the center of the peninsula; noted for the Palacio del Infantado.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

At 708 metres above sea level, Guadalajara’s evening air arrives five degrees cooler than Madrid’s. Office workers stepping off the 18:07 from Chamartín loosen their ties and order cañas outside bars on Plaza de Santo Domingo while the capital below still bakes on the plain. The altitude matters more than the map suggests: winters bring sharp frosts, spring arrives two weeks later, and in August madrileños drive here for breathable nights rather than monuments.

A palace that borrowed the Renaissance

The Palacio del Infantado dominates every postcard, yet its showiest feature is pure 15th-century bling. Diamond-pointed stonework covers the entire facade like studded leather; the lions in the courtyard smirk rather than roar. Inside, the provincial museum charges no admission on Sunday mornings and devotes an entire floor to local ironwork, including a set of 16th-century manacles that once decorated the city jail. Most visitors photograph the patio and leave; linger and you’ll have the upper galleries almost to yourself, with views straight down the Henares gorge.

Five minutes away, the Concatedral de Santa María keeps a lower profile. Brick and stone are laid in the alternating bands of mudéjar technique, a reminder that medieval Guadalajara answered to both Christian bishops and Muslim master-builders. The tower looks unfinished because it is: the money ran out in 1392 and no one ever added the spire. Locals use the excuse to claim their skyline is “honestly medieval” compared with postcard-perfect Sigüenza up the road.

Where the river still dictates lunchtimes

The Henares loops tightly around the old quarter, creating a natural air-conditioner. Walk the restored Arab bridge at 11 a.m. and the water smells of mint and damp stone; by mid-afternoon the same spot is a sun-trap and sensible people retreat indoors. River cafés therefore serve lunch late—don’t expect a table before 2:30 p.m.—and reopen for merienda (tea-time tapas) around 5 p.m. British stomachs should plan accordingly: a 1 p.m. sandwich marks you as a foreigner.

Behind the church of San Ginés, the 19th-century covered market still does half its trade in honey. Alcarria bees work the rosemary and thyme slopes east of town; the result carries a faint lavender note and sells for €8 a kilo, cheaper than in Borough Market by roughly the cost of a return flight. Stallholders will dribble the same honey over fresh cheese if you ask; the combination tastes like deconstructed cheesecake minus the biscuit base.

Trains, plains and hire-car pains

Guadalajara’s high-speed station sits 5 km south-west of the centre, a legacy of the AVE line being punched through open farmland in 2003. Regional buses connect every half-hour (€1.40, 12 minutes) but finish at 22:00; miss the last and a taxi costs €12 flat. Hire cars collected at the station come with a warning: satellite navigation still sends drivers along the old N-II, a truck-choked dual carriageway that shaves off no time. Ignore the screen, follow the A-2 bypass, and you’ll reach Brihuega’s lavender fields in 35 minutes.

Without wheels, day-trips require patience. Buses to Sigüenza run twice daily, timed for pensioners rather than tourists, and the Sunday service is cancelled if the driver is rostered off. The railway to Soria passes through Atienza, but the station is 7 km below the village and taxis must be booked a day ahead. In short: base yourself here only if you’re content to potter; otherwise hire a car or accept that you’ll see fewer hill towns.

The fiesta that empties the supermarkets

From 5 to 12 September the Feria de Guadalajara turns orderly streets into a movable feast. Pop-up bars installed in Calle Mayor serve tinto de verano for €2 a glass; supermarket shelves of chilled rosé are stripped bare by Wednesday. The council lays on free concerts in Parque de la Concordia—past bills have included Everything Everything and a Kylie tribute act—then finishes each night with fireworks that echo off the palace walls. Hotel prices don’t triple as they would in Seville, but rooms overlooking the fairground receive free decibels until 4 a.m.; light sleepers should request the rear.

Out of season, the city slips back into provincial rhythm. University students on the new health-science campus keep cafés busy, yet you’ll still find shopkeepers closing for two hours at lunch. British visitors sometimes interpret the shuttered fronts as economic decline; in fact it’s the continuation of a siesta tradition Madrid abandoned decades ago.

Winter coats and summer siestas

Elevation works against the city from November to March. Night temperatures flirt with zero, and the palace courtyard holds onto cold air like a fridge. Snow is rare, but the wind that barrels down the Henares valley can make 5 °C feel like minus two; pack a proper coat rather than a fleece. In compensation, bars keep log burners going and serve ponche alcarreño, a hot mix of local gin, honey and lemon that tastes like alcoholic Lemsip without the medicinal shame.

Summer reverses the deal. July averages 32 °C at midday, yet humidity stays low and evenings drop to 18 °C—perfect for terrace life. Hotels on the north bank (the newer part) have the advantage here: their rooms face away from the afternoon sun and cost €10 less than the old-town boutique options. Air-conditioning is standard, but many locals still draw the shutters and sleep through the hottest hours, reopening shops at 6 p.m. when shadows stretch across the plazas.

What Brits miss (and how not to)

The common mistake is to treat Guadalajara as a single-monument stop on the way to somewhere else. Coach parties march from bus to palace, photograph the patio, then depart for Toledo having seen nothing of the river, market or honey stalls. Allocate at least one night and you overlap with Spanish weekenders who arrive Saturday morning, browse the antique book fair in Plaza de los Caídos, and disappear after Sunday lunch—leaving the city agreeably quiet for Monday exploration.

Second error: assuming food will be heavy. Yes, the local roast kid tastes like turbo-charged Welsh lamb, but portions are modest by Castilian standards and most restaurants will swap chips for salad if asked. Vegetarians survive on migas made with peppers rather than chorizo, and the university crowd has spawned two vegan cafés on Calle de la Trinidad—an oddity in a province famed for pork.

Finally, remember the name. Type “Guadalajara” into a flight search engine and you’ll be offered eleven hours to Mexico. Add “Spain” or “Castilla-La Mancha” and the journey collapses to two hours plus a 30-minute train. It’s a small detail, but one that saves you from an unwanted transatlantic surprise.

Guadalajara won’t change your life. It will, however, give you a Spain that feels lived-in rather than curated, where palace entry is cheap, the honey is honest and the evening breeze actually works. Bring an appetite, a light jacket and a tolerance for late lunches; the city will handle the rest.