Full Article

about Almonacid de Toledo

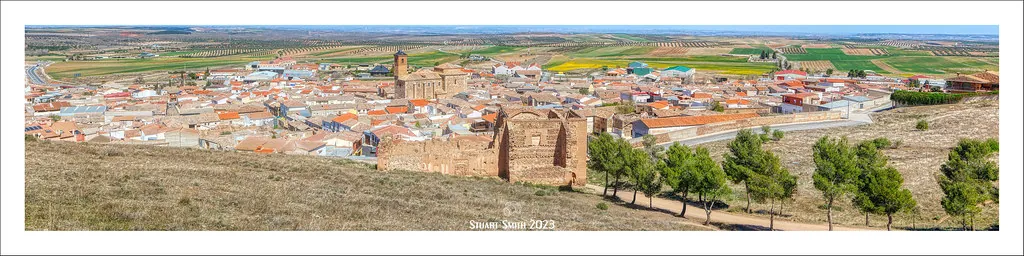

Historic town known for its castle and a Napoleonic battle; on the Don Quixote Route

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The only sound at eight o’clock on a Tuesday morning is the echo of your own boots on stone. Almonacid’s single bar has pulled its metal shutter halfway up, but the plaza is still empty except for a white van delivering bread and a teenager coasting downhill on a battered BMX. From any street that faces north you can see the castle ruin above the roofs, the tower leaning like a broken tooth against a sky already the colour of bleached denim. It is 720 metres above sea-level, 45 minutes south-west of Toledo, and it feels twice as far from anywhere that accepts credit cards.

The Hill and What’s Left of the Fortress

A brown sign points you past the cemetery; after that the tarmac stops and the slope begins. What used to be a medieval approach road is now a stony farm track wide enough for one tractor. Twenty minutes of steady climbing brings you to a crumbling curtain wall and an entrance where the gate has not existed for centuries. Inside, the ground is littered with masonry the size of airline trolleys and, in spring, poppies grow through the gaps. There are no information panels, no safety ropes, no ticket desk—just the tower keep still standing to its full height and views that swallow half of La Mancha.

Look north and the plain stretches away like a rumpled yellow table-cloth all the way to the wind turbines outside Toledo. Southwards the olive groves break up into holm-oak dehesa and, on a clear day, you can just make out the first ridges of the Montes de Toledo proper. Bring binoculars: griffon vultures use the thermals that rise off this hill, and locals swear they have seen Spanish imperial eagles harrying the kites. The wind is constant; in February it will chap your cheeks, in August it feels like someone aiming a hair-dryer at your face. Either way there is no shade—pack water and a hat or the ridge will send you back down faster than the gradient.

Streets Built for Donkeys, Not Deliveries

The village clings to the southern flank of the same hill. Houses are whitewashed but not prettified: television aerials trail like spaghetti, and the odd front door is still the original timber, painted the dark ox-blood colour that shows where the iron oxide primer has bled through. Alleyways are barely two metres wide; if you meet a neighbour coming up with shopping you flatten yourself against the wall and exchange buenos días while the plastic bags brush your knees. There is no craft trail, no boutique olive-oil outlet, just a chemist, a grocery the size of a London newsagent, and a cooperative store that sells five-litre cans of local oil for six euros—cash only.

The parish church of San Bartolomé squats halfway up the gradient, its bell-tower doubling as the village clock. Step inside and the air smells of candle wax and the damp plaster that comes with a roof repaired too many times. A sixteenth-century retablo fills the sanctuary; the carved apostles have had their faces touched smooth by centuries of parishioners reaching up on saints’ days. Mass is at eleven on Sundays; if you arrive early you will see widows in black negotiating the cobbles with the determination of veteran hill-walkers.

Eating What the Fields Give Back

Mid-week lunch is served in the bar on Plaza de la Constitución, the only place still flying the menú del día flag. A bowl of patatas con costillas—potatoes, ribs, sweet paprika and enough garlic to keep Dracula away—costs €9 and arrives in the same terracotta dish it was baked in. There is no choice beyond “¿pan o no?” and the television in the corner will be showing the previous night’s football highlights whether you watch or not. If you are here in August for the fiesta you can queue at a side street stall for hornazo, a saffron-coloured pie containing a whole boiled egg; it is designed for eating while balancing on a bar stool made from an upturned crate.

Buy wine at the doorway opposite the church: Finca Romaila’s Cencibel (the local name for Tempranillo) is sold by the litre from a stainless-steel vat for €2.50. Bring your own bottle or they will rinse a plastic water container. It is young, fruity and no worse than many high-street Riojas costing four times as much back home.

Walking It Off

From the castle you can loop east along the GR-109 footpath, way-marked with white and yellow slashes. The track dives into holm-oak woods where wild boar root among last autumn’s acorns and the only sound is cicadas and the click of your walking poles. After 5 km the path drops to a ford across the Torcón river; in May the water is knee-deep and welcome, by late July it is a string of algae-rimmed pools. Allow three hours for the circuit back to the village, or press on south to the abandoned ergástula—a Roman slave prison—where the stone walls are still blackened by medieval shepherds’ fires.

If you would rather stay closer, follow the ridge west for twenty minutes at sunset. The oak trees thin out, the land falls away, and you can watch the sun sink behind the wind turbines, their blades flashing like railway signals in the gloom. Head-torches are useful; the descent is ankle-twisting territory after dark.

Getting Here, Getting Out

Public transport exists but it feels theoretical. One ALSA bus leaves Toledo’s estación de autobuses at 14:00 on weekdays and returns at 06:55 the next morning. That is it—no Sunday service, no late option. A taxi from Toledo costs about €35 if you telephone in Spanish and do not mind waiting twenty minutes while the driver finishes his cortado. Once in the village a car is pointless except for leaving; the streets were designed for mules and a modern SEAT will scrape its wing-mirrors.

When the Weather Turns Nasty

Storm clouds pile up fast here because the plateau has nothing to stop them. When rain arrives the castle track becomes a clay slide and trainers turn into two-kilo clogs. Winter nights drop below freezing; the village fountain ices over and the smell of wood smoke drifts through every chimney. Summer, on the other hand, is an endurance test. By two in the afternoon the stone walls radiate heat like storage heaters and shade is as rare as an English breakfast. Start walking at dawn or wait until the sun has brushed the horizon; the mid-day hours are for siesta, not sightseeing.

Last Orders

Almonacid will not entertain you. It offers a hill, a ruin, a plate of stew and a sky big enough to make your concerns feel trivial. If that sounds like too little, stay in Toledo and take the tourist train. If it sounds like just enough, fill your water bottle, pocket a four-euro note for wine, and start climbing before the village wakes.