Full Article

about Peñafiel

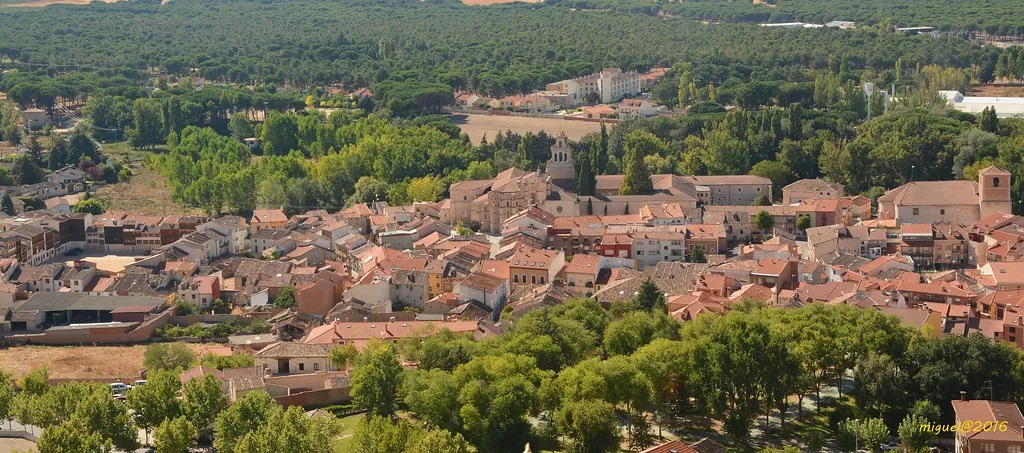

Cradle of Valladolid’s Ribera del Duero; known for its ship-shaped castle and the Plaza del Coso.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

From the Valladolid road the castle first appears as a long stone hull slicing through rows of tempranillo vines. The silhouette is so deliberate, so ship-like, that drivers instinctively slow as if approaching a dry-dock rather than a 15th-century fortress. This is Peñafiel’s calling card: a 200-metre warship of sandstone parked 754 metres above sea level, guarding a town that has lived off lamb and wine since the monks arrived.

The climb from car park to rampart takes fifteen minutes and works up a thirst that the region fully intends to satisfy. Inside the keep, the Museo del Vino de Valladolid spreads across four floors of interactive displays, copper stills and a 17th-century press. English labels are thin on the ground, but the message is clear enough: Ribera del Duero reds owe their backbone to altitude, diurnal swing and soils that look like broken biscuit. A tasting glass is included in the €8 ticket; sip on the battlements and the view runs south across a checkerboard of vineyards that supply names now stocked in Waitrose.

Back in the maze of ochre lanes, the Plaza del Coso stops first-time visitors in their tracks. Houses form a complete ring, their timber balconies jutting out like theatre boxes. The space doubled as a bull-ring until 1974 and still hosts corridas during the September fiestas; on ordinary mornings it is simply the neighbourhood square where pensioners walk dogs and teenagers kick footballs against stone that once absorbed horns and capes. Knock on door number 14 and the owner may let you upstairs for the price of a coffee – the sight-line into the arena is free, the story priceless.

Religion here is sturdy rather than soaring. The Iglesia de San Pablo keeps its Gothic-Mudéjar feet firmly on the ground, while the Convento de San Pablo turns a cloistered shoulder to the modern world. Neither will keep you longer than twenty minutes, but together they explain why a frontier town of five thousand souls once needed four parishes and two convents: wine tithes paid for stone, and stone advertised power.

Cellars Below, Cep Above

Peñafiel’s real cathedral is subterranean. More than 200 bodegas are scooped under the hill, their entrances disguised behind timber doors no taller than a shepherd. Temperature holds steady at 12 °C winter and summer, perfect for sleeping wine and overheated visitors alike. Family operations such as Bodegas Peñafalcón or Casimiro will open a 16th-century gallery if you e-mail the day before; tours end with roast-lamb crisps and a glass of crianza poured by the same woman who stamped your ticket. No gift shop, no multimedia, just the faint smell of oak and the knowledge that the bottle in your hand never saw a motorway.

If you prefer labels you already recognise, head five minutes out of town to Protos or Alejandro Fernández. Their architect-designed headquarters offer polished tastings in six languages and views through frameless glass, but the experience comes with coach parties and a schedule. Book the 11 a.m. slot and you’ll be back in the centre for lunch before the Spanish office workers have finished their coffee.

Eating on Castilian Time

Lunch starts at 14:00, dinner rarely before 21:30 – plan accordingly or stomachs will rumble audibly in the empty streets. Lechazo asado is the local religion: milk-fed lamb slow-roasted in oak-fired clay ovens until the skin crackles like parchment. A quarter-kilo portion feeds two, costs around €24 and tastes milder than Welsh hill lamb, with none of the grassy tang that puts off fussy eaters. Morcilla de Burgos arrives as fat black coins shot through with rice; order it grilled and the centre stays creamy rather than the dry crumble familiar from British fry-ups. Cheese is strictly sheep: try the six-month curado anywhere on the square and you’ll wonder why Manchego gets all the airport shelf space.

Vegetarians survive but do not thrive. Most kitchens will assemble a pimientos de Padrón plate or a judión bean stew, yet menus still list “ensalada” as a single option between tripe and tongue. Bring protein bars if you’re plant-based and self-catering apartments are scarce – the reliable escape is Hotel Ribera del Duero on Paseo de Zorrilla where rooms with castle vistas run €65–75 and reception will phone ahead to secure meat-free tapas.

Walking Off the Wine

The town itself is walkable in twenty minutes, but surrounding vineyards offer flat tracks that sober up both legs and heads. Pick up the signed Ruta del Duratón from the medieval bridge: the path hugs the river for 5 km, looping back through allotments where grandfather figures hoe artichokes in suit jackets. October turns the vines traffic-light red; May brings almond blossom and temperatures that British walkers describe as “Yorkshire summer, minus the rain”. Either season beats July and August when the meseta hits 38 °C and shade is rationed to one plane tree per square.

Serious hikers can drive 25 minutes to the Hoces del Duratón Natural Park for griffin-vulture viewpoints and 300-metre limestone cliffs. Peñafiel works as a lazy base: leave the car in the free car park by the health centre, stroll to the castle for opening time, then decide between a second tasting or a siesta. Distances are short enough that nothing is more than a ten-minute stagger away.

Getting There, Getting In

Madrid-Barajas is the sensible gateway: collect a hire car, join the A-6, switch to the A-11 at Venta de Baños and roll into town ninety minutes later. Valladolid airport is closer (45 min) but Ryanair’s London-Stansted service hibernates between November and March; Madrid stays reliable year-round. Trains reach Peñafiel from Chamartín in 1 h 20 min for about €20 if booked a month ahead, though you’ll still face the uphill slog to the castle unless a taxi is waiting.

Tuesday to Sunday the fortress admits visitors until 45 minutes before close; Mondays it slams shut like a medieval drawbridge. Entry is €8 and includes both wine museum and rampart wander – cash or card, but have coins ready for the centre’s €1.20-per-hour blue zone. ATMs take the day off on local fiestas, so withdraw before the processions start.

When to Book, When to Avoid

Semana Santa and the September harvest festival sell out three months in advance; accommodation triples and restaurant owners stop answering the phone. Conversely, January feels suspended: bright sun, frost on the vines, menus del día for €12 and hotel staff delighted to see a foreign face. Spring and autumn split the difference – warm days, cool nights, tables available on spec – which is why repeat visitors from Birmingham and Bordeaux time their trips for late April or mid-October.

Peñafiel will never shout. It has neither beach nor ski-lift, no Gaudí whiplash or Michelin constellation. What it offers is a concentrated shot of interior Spain: castle, wine, lamb and the unhurried rhythm of a place that has been shipping reds long before Britain learnt to say “tempranillo”. Arrive with an appetite and a spare suitcase; leave with purple teeth and the realisation that sometimes the best destinations are the ones content to stay exactly as they are.