Full Article

about Vallecillo

Small village with traditional caves; set in cereal-growing flatlands.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell strikes noon, and the only other sound is grain stalks brushing against each other in the breeze. At 837 metres above sea level, Vallecillo sits high enough for the air to carry clarity but not enough to warrant altitude warnings. This is Castilla y León's plateau at its most honest—no postcard perfection, just a village of roughly one hundred souls where the 21st century arrives through fibre optic cables rather than tour coaches.

The Geography of Stillness

From León's provincial capital, the A-60 motorway spits you out at Sahagún, twenty-five minutes west. Another fifteen on the CL-610 and you're here, watching the horizon flatten until even the modest rise beneath Vallecillo feels like topography. The village occupies a slight elevation—enough to spot weather approaching across cereal fields that stretch towards Portugal.

These fields dominate every vista. Wheat, barley and increasingly peas rotate through seasons that swing from frozen fog in January to parched earth in August. Spring brings an almost violent green that lasts roughly six weeks before burning to gold. Autumn arrives abruptly, usually overnight in mid-October, painting everything ochre except for the occasional holm oak that farmers leave standing—landmark rather than woodland.

The altitude matters more than you'd expect. Nights run ten degrees cooler than Madrid year-round, making that packed fleece useful even in July. Winter requires proper coats; the meseta's continental bite delivers minus figures regularly, though snow rarely settles longer than a day. The compensation comes after dark: zero light pollution means Orion appears close enough to touch, while satellites track silently across skies that inspired nothing more dramatic than medieval shepherds' campfire stories.

Architecture Without Pretence

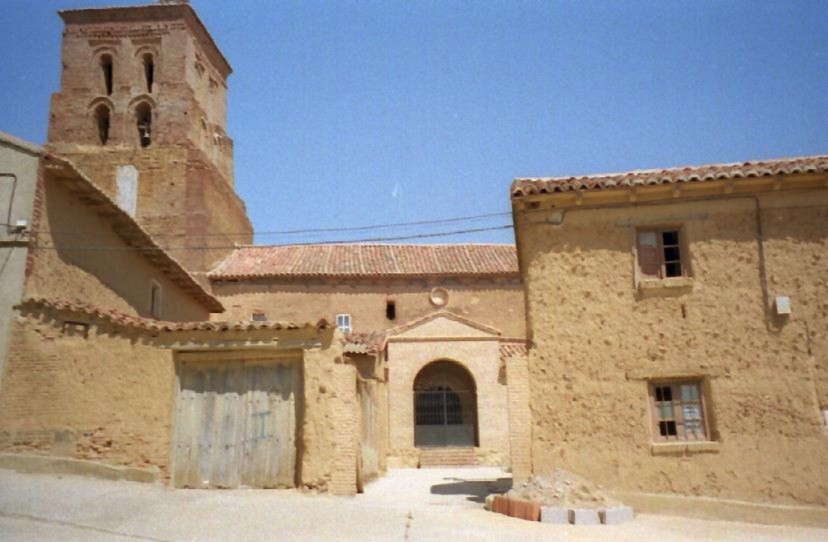

Vallecillo's church won't feature in guidebooks, and locals prefer it that way. The 18th-century brick tower rises modestly above single-storey houses, its bell still summoning the faithful—or more accurately, marking time for everyone regardless of belief. Step inside during Sunday mass (11:00, duration thirty-five minutes) to see how rural Catholicism functions when congregation size rivals choir numbers elsewhere.

Surrounding streets reveal building materials that preceded cement: adobe walls thick enough to swallow mobile signals, stone foundations quarried from nearby fields, and tapial (rammed earth) structures that survived centuries through sheer thickness. Wooden gates hang from iron hinges forged in Sahagún's workshops before industrialisation. Some properties display fresh render and double-glazing; others crumble quietly behind corrugated iron fences. This mix isn't photogenic, but it honest—villages either evolve or become museum pieces, and Vallecillo chose evolution.

The plaza contains no cafés, no souvenir stalls, not even benches manufactured for Instagram moments. Instead, residents drag plastic chairs outside houses during summer evenings, creating impromptu social clubs that disperse when mosquitoes emerge. Someone usually produces a guitar; someone else brings homemade orujo that tastes of anise and regret. Visitors joining these circles learn quickly: speak Spanish, accept the offered drink, and prepare for conversations ranging from EU agricultural policy to why British people boil vegetables into submission.

Moving Through Landscape

Walking options start literally at the village edge. A network of agricultural tracks—wide enough for combine harvesters—connects Vallecillo with neighbouring hamlets like Santibáñez de Ayuso and Calzada del Coto. These paths follow historic drove routes; merchants once moved sheep towards Sahagún's medieval fairs along the same lines. Today you'll share them with tractors and the occasional 4x4, but rarely other pedestrians.

The circuit to Santibáñez measures six kilometres, dead flat except for one drainage dip where red kites often circle overhead. Spring brings calandra larks displaying above fields, while autumn sees harriers hunting migrating songbirds. Take water—shade doesn't exist and locals judge dehydration victims harshly. Sturdy footwear handles the crushed-stone surfaces, though trainers suffice outside rainy periods when clay turns everything slippery.

Cyclists find rolling terrain that seems designed for steady cadence rather than Strava segments. The CL-610 towards Sahagún carries minimal traffic early mornings; secondary roads spider-web across plateau offering fifty-kilometre loops that never exceed three percent gradients. Headwinds provide the main challenge—this is Spain's answer to East Anglia, with weather systems that forgot mountains exist. Bike shops? None. Bring tubes, pumps and realistic expectations about mobile reception during mechanical failures.

Eating and Drinking Reality

Let's manage expectations immediately: Vallecillo contains zero restaurants, one bakery open three mornings weekly, and a village shop stocking basics plus surprisingly good local cheese. Self-catering isn't optional unless you're invited to someone's table—an honour requiring linguistic effort and tolerance for lamb-heavy menus that would distress vegetarians.

The nearest proper meal sits eight kilometres away in Calzada de los Molinos at Mesón El Cencerro. Their menú del día costs €12 Monday-Friday, featuring judiones (giant white beans) stewed with chorizo, followed by lechazo—milk-fed lamb roasted in wood-fired ovens until spoon-tender. Portions challenge normal appetites; sharing starters between two still leaves enough for Spanish grandfathers who grew up during rationing. House wine arrives in unlabelled bottles and performs better than British supermarket own-brands costing triple.

Weekend options expand in Sahagún, where brick-built Romanesque churches outnumber traffic lights. Restaurante Posada de Sahagún serves cocido maragato—the local stew eaten backwards (meat first, chickpeas last, don't ask why) that requires subsequent horizontal time. Their €18 weekend menu includes it, plus dessert and coffee strong enough to restart conversation after food coma subsides.

When to Show Up, When to Avoid

April delivers the plateau's brief fertile explosion—green fields under blue skies with temperatures hovering around 18°C. Wildflowers appear in drainage ditches; birdsong actually becomes noticeable after winter's silence. This is also when local farmers burn stubble, so some days carry agricultural haze that photographs terribly but smells authentically rural.

July brings fiestas patronales, the one week when Vallecillo's population quadruples. Returning emigrants transform quiet streets into something approaching lively, with nightly verbena dancing in the plaza and communal paellas requiring advance ticket purchase. Accommodation within village limits doesn't exist—book Sahagún hotels early or accept hour-long drives from León province's limited rural guesthouses.

November through February empties the landscape completely. Days shorten to eight hours; fog frequently swallows visibility beyond fifty metres. Yet these months offer something increasingly rare—absolute silence broken only by church bells and your own footsteps. Bring books, download films, embrace the hermit experience. Mobile coverage works fine for streaming, though locals will judge you harshly for watching Netflix while real life occurs outside.

The honest truth? Vallecillo rewards those seeking Spain's agricultural reality rather than its tourist fantasy. Come prepared for self-reliance, basic facilities, and conversations requiring phrasebook Spanish. Leave expecting nothing beyond what a small farming community provides: genuine human interaction, skies that remind you Earth's atmosphere exists, and the slow realisation that "nothing to do" actually means "finally, time to just be."