Full Article

about Tordesillas

Historic town where the world was divided; home to the Royal Monastery of Santa Clara and the Treaty Houses.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The treaty that rewrote the map

Inside the Casas del Tratado, a small stone mansion on Tordesillas' main street, hangs a 1494 parchment that once sliced the planet in two. The document is faded, the Latin cramped, yet its audacity still startles: Spain and Portugal drew a vertical line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands and agreed that everything to the west belonged to Castile, everything to the east to Lisbon. Half a millennium later the room smells faintly of old paper and wood smoke, and a British visitor can stand precisely where ambassadors initialled a deal that would eventually hand Brazil to Portugal and the rest of the Americas to Spain. No one mentioned Britain, of course; at the time Henry VII was more worried about keeping the Tudors on the throne than discovering new ones.

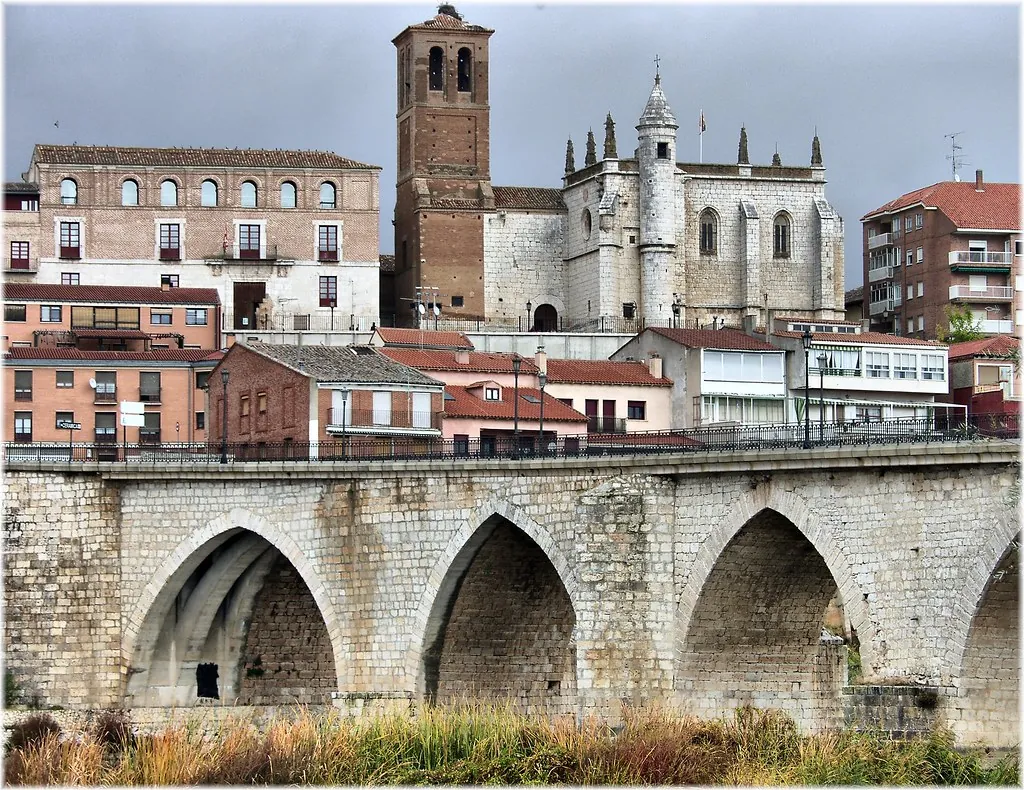

That sense of being left out of the story makes Tordesillas oddly satisfying. The town isn't spectacular, just quietly confident. Stone arcades shade the Plaza Mayor, cafés charge €1.40 for a caña, and the Duero slides past below a rebuilt medieval bridge. At 704 m above sea-level the air is thinner than on the coast but not sharp; spring mornings are warm enough to sit outside, autumn evenings bring a quick chill that justifies the local habit of serving roast lamb with strong, young red wine.

Juana the Mad's half-century lock-in

A five-minute walk north of the treaty house takes you to the Real Monasterio de Santa Clara, a fourteenth-century convent where Joan of Castile – Juana la Loca – spent 46 years under what polite guides call "preventive custody". The building began life as an Almohad palace; its horseshoe arches, patterned stucco and sunken Arab baths survive intact, patched into later Christian brickwork. Tours (€6, hourly, book at the kiosk) thread through the queen's private oratory, a bare cell with a slit window looking onto the cloister, then down into the hammam where the nuns now store plastic chairs. Guides speak slow, clear Spanish and hand out English crib sheets; even so, the story they tell is more tabloid than textbook – jealousy, political paranoia, a husband who died too young, a father who wanted the crown, a son who kept her locked away. Whether Juana was mad, inconvenient or simply dangerous depends on which century you ask.

Outside, swallows nest in the bell tower and the town's loudspeaker system plays an instrumental version of "Yesterday". Couples photograph each other on the Mudéjar staircase; no one seems sure whether to smile or look solemn.

Flat walks and full stomachs

Tordesillas stretches barely a kilometre from bridge to convent, so sightseeing happens on foot and takes half a day. The fifteenth-century San Antolín church lifts a Renaissance tower above the Plaza Mayor; inside, gilded baroque altarpieces glow dimly until someone drops a coin in the box and the lights flick on like a late-night fridge. Round the corner, the Museo del Encaje displays tablecloths that took three years to knot, guarded by volunteers who demonstrate the technique with the resigned patience of people who have seen every possible selfie angle.

When the museums close, the town keeps going. A signed path leads south along the Duero for 4 km through poplars and allotments; cyclists share the track with men casting fishing lines for carp they swear they never eat. Across the river the cereal plateau opens out, gold stubble in July, deep-green vines in May. There is no dramatic gorge, just a wide, workable valley that explains why people have been crossing here since the Romans cut the first planks.

Back in the centre, lunch starts at 14:00 sharp. Mesón Plaza Mayor will sell you a quarter-roast suckling lamb (€24) bronzed in a wood-fired oven; the meat collapses at the nudge of a fork, the skin shatters like hard caramel. If that feels excessive, most bars dish out tapas-sized raciones: cecina (air-dried beef) draped over grilled piquillo peppers, or a clay bowl of judiones – butter-fat white beans stewed with chorizo and bay. Vegetarians survive on tortilla and roasted piquillos, though they may get bored after the second evening. Wine comes from local cooperatives; expect robust tintos at €2.50 a glass, nothing fancy but honest enough to wash down the grease.

Thursday market and other living habits

Thursday is market day. Stallholders drive in from surrounding villages and lay out cheeses the size of tractor wheels, knobbly misshapen peppers and vacuum-packed morcilla that travellers can legally take home within the EU. The market colonises the northern streets from 09:00 to 14:00; if you arrive at 09:05 you will find a parking space. At 11:30 the cafés around the square are full of farmers arguing about barley prices over cortados. Tourists are noticed but not mobbed; English is understood slowly, French better, cash preferred.

Evenings follow the Castilian timetable: siesta shutters stay down until 17:30, then children kick footballs against the church walls while parents nurse vermouths. By 22:00 the same squares are loud with gossip; by 23:30 most voices have moved indoors, leaving only the hum of refrigeration units and the occasional scooter echoing under the stone.

Getting there, getting out

Tordesillas sits 30 km southwest of Valladolid on the A-62. From Madrid the drive takes two hours on the A-6 and A-62; tolls amount to €16 each way. ALSA runs four daily coaches from Madrid Estación Sur (2 h 15 min, €16). Once in town everything is walkable; the tourist office beside the bridge lends multilingual audioguues against a €20 deposit you get back if you return the device intact.

Staying overnight makes sense if you want to eat lamb without driving afterwards. The Parador de Tordesillas, five minutes out in pine woods, offers swimming-pool comfort from €110 B&B; inside the walls the three-star Hotel Real de Castilla has smaller rooms but includes underground parking (€12) and lets you stagger straight into the bars. Book the monastery tour online at weekends – Spanish families turn up and morning slots sell out.

Leave early next day and you can be in Salamanca for coffee, or back in Madrid before lunch. Tordesillas won't change your life, but for a few hours you can walk the same flagstones as ambassadors who thought they owned half the planet, and taste lamb that makes the detour worthwhile.