Full Article

about Magaña

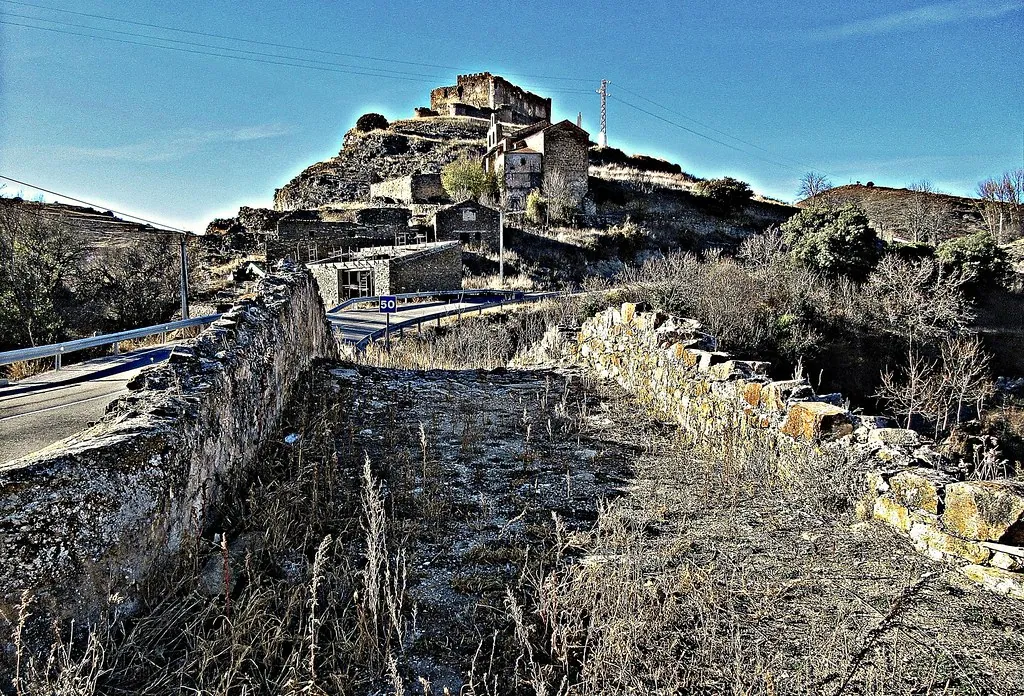

Dominated by the imposing Castillo de Magaña above the Alhama river

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

Sheep block the single-lane road at 9:30 a.m. and nobody bothers to honk. The shepherd leans on his crook, two dogs circle the flock, and the only sound is cloven hooves scraping granite. Welcome to Magaña, population sixty-three on a good Friday, 980 metres above sea-level and light-years away from the Costa-del-anything.

The village squats on the Soria side of the Riojan frontier, a stone-and-timber cluster that forgot to update itself. Stone slabs bridge the gutters, timber balconies sag under the weight of snow winters, and every roof angles sharp enough to shed whatever the sky throws at it. Granite is the local vernacular: dark, glinting, unapologetically hard. You notice it first in the low walls, then in the church bell-tower, finally in the expression of the baker who opens his garage-door “shop” only when he feels like it.

How to Arrive Without a Bus

Public transport ends at Soria, twenty-five minutes south on the N-111. From Madrid-Barajas you collect a hire-car, join the A-2, then peel off towards the Duero gorge. After the industrial estates thin out, the road climbs through wheat and pine until the dashboard thermometer drops six degrees and phone bars vanish. Sat-nav will swear you have arrived; the only landmark is a hand-painted board reading “Magaña, Tierras Altas”. Turn right before the cattle-grid, mind the pothole that swallows the nearside wheel, and park wherever the tarmac stops. Parking meters haven’t been invented here.

What You’ll Notice First

Silence, then wood-smoke. The village faces north-east into the wind, and even in May someone lights a stove at dusk. Narrow lanes funnel the breeze until it whistles; bring a jacket whatever the calendar says. The church of San Pedro is locked unless it’s Sunday, but the key hangs on a nail inside the sacristan’s porch—knock loudly. Inside, the nave is dim, whitewashed, smelling of candle grease and old wool. A single baroque retablo gilded in 1721 glimmers like a struck match. Donations go in a tobacco tin; leave a euro or two for the roof fund.

Below the church the land falls away into a pine ravine where griffon vultures ride the thermals. Walk fifteen minutes down the dirt track and you reach the abandoned hamlet of Los Casares, roofs gone, ivy pouring through the windows. It’s Border-country history in brick form: emptied during the rural exodus of the 1960s, when Madrid promised wages that the mountain couldn’t match. Stone bread-ovens still stand, blackened mouths gaping like whales.

Walking Without Waymarks

No gift-shop sells a glossy map; instead, ask in the plaza for Paco. He’ll appear in overalls, wipe tractor oil off his hands and sketch three routes on the back of a fertilizer sack. The easiest skirts the ridge to an old snow-pit where ice was once cut and hauled to the village on mule-back—ninety minutes round trip, trainers acceptable. The second follows the GR-86 long-distance path south-west to Vinuesa reservoir, thirteen kilometres through pine and juniper, returning by the lakeshore road if legs mutiny. The third climbs Cerro Castillo (1,320 m), a calf-burning hour on loose shale rewarded by a view that stretches, on very clear days, to the Obarenes mountains above Haro’s bodegas forty kilometres away. Marking is sporadic: cairns, the occasional yellow splash, common sense. Take water—there are no fountains above the village and summer temperatures can still hit thirty degrees before noon.

Autumn brings mushroom pickers wielding wicker baskets and pocket knives. Níscalos (saffron milk-caps) flush after the first September rains; locals guard spots with the same jealousy a Yorkshireman reserves for his fishing swim. Permits are free from the town hall in Abejar but nobody checks unless you emerge with industrial crates. Boletus edulis appears later under the oaks; slice, fry in olive oil, freeze in yoghurt pots—mountain caviar for winter stews.

Food, Beds and the Lack Thereof

Magaña has zero hotels, zero bars, one baker open two mornings a week. Plan accordingly. Self-catering cottages have begun to appear—Casa del Tejado, Casa del Portón—both restored by grandchildren of the original owners, both booked solid at Easter and during August fiestas. Expect stone floors, beams blackened by centuries, Wi-Fi that flickers when the wind changes. Nightly rates hover round €90 for two, minimum stay two nights; firewood is extra and delivered by wheelbarrow.

Meals happen in Soria unless you brought supplies. The provincial capital serves one of Castilla’s better lechazo (milk-fed lamb) at Mesón Castellano—order a quarter roast for two, €28, crisp skin giving way to meat you could spread with a spoon. Vegetarians survive on tortilla del Sacristán (thick, potato-heavy) and setas a la plancha; request “sin jamón” twice because the concept of pork seasoning still puzzles many chefs. Stock up at the Mercadona on the Soria ring-road before heading uphill; Magaña’s only shop sells tinned tuna, tinned peas and, inexplicably, birthday candles.

When to Come, When to Stay Away

April–June delivers daylight until nine-thirty and meadows loud with larks. Mornings start frosty, afternoons hit twenty-two degrees—layer like an onion. September glazes the oak canopy copper; the harvester hums in the wheat valley and the smell of crushed grapes drifts up from Rioja thirty minutes north. July and August are hot, cloudless, thunder-cracked. Village houses stay cool but the walks bake; set off at dawn or forget it. Mid-winter is Siberian: snow from December to March, roads periodically closed by drifting powder. The place looks Christmas-card perfect for exactly three hours, then pipes freeze and the generator coughs. Unless you relish chopping kindling in a blizzard, visit on a day-trip from Soria rather than overnight.

August 15 brings the fiesta patronal: mass at noon, paella the size of a paddling pool, plastic tables dragged into the single street, town-hall speakers playing Spanish eighties rock until the Guardia Civil suggest midnight might be neighbourly. Accommodation is impossible that weekend; book twelve months ahead or time your escape before the brass band strikes up.

Parting Shots

Magaña will not change your life. It offers no souvenir magnets, no Michelin stars, no yoga retreats. What it does provide is a calibration exercise: a reminder that Spain still contains places where the loudest noise is a church bell cast in 1783 and the evening entertainment is watching the sky turn from slate to rose behind the pines. Bring boots, a phrasebook and a cool-box. Expect to leave with bruised shins, a full memory card and the uncomfortable realisation that sixty-three people have worked out something the rest of us keep missing.