Full Article

about Vilabertran

Home to a first-rate Romanesque canonry; known for its music festival.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

Stone, Silence and the Scent of Bread at Dawn

The bakery on Carrer Major switches on its lights at half-past five. By six, the first warm cocas – flat-breads freckled with escalivada – are sliding onto the counter, and the whole village smells of olive oil and wood smoke. This is the moment to start walking: before the Figueres traffic builds, before coach parties from Roses discover the car park holds only twenty-five spaces, while the monastery bells still belong to the swifts rather than the loudspeakers.

Vilabertran sits three kilometres inland from the N-II, low enough (nineteen metres above sea level) to feel Mediterranean, yet far enough from the sea to escape the summer rental stampede. Its 1,000-odd inhabitants live in a grid of stone houses that never grew beyond medieval boundaries; no apartment blocks, no neon, just the slow erosion of cobbles by generations of farmers heading to market with crates of Empordà peaches.

A Canonical Surprise in Plain Sight

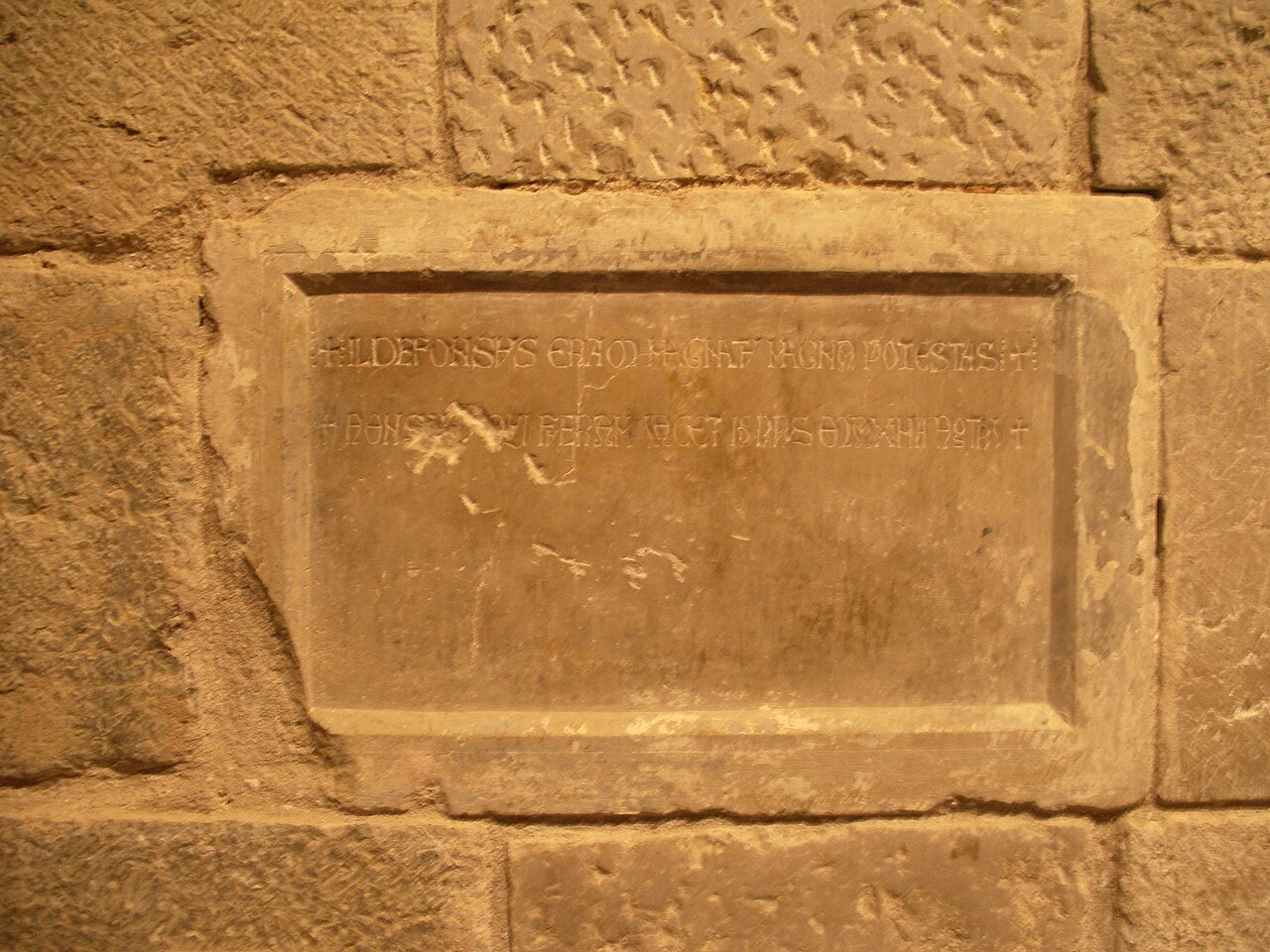

The guidebooks call the Canònica de Santa Maria “one of Catalonia’s finest Romanesque complexes”. What they forget to mention is how the façade jumps out at you after a turn so tight you could touch both walls. One moment you’re admiring somebody’s geraniums, the next you’re staring up a twelfth-century bell tower that looks transplanted from Lombardy and dropped intact on this flat agricultural plain.

Inside, the church is mercifully free of baroque gilt excess. Three naves, sober proportions, light filtering through alabaster rather than stained glass. The real pleasure is the cloister: slender double columns, capitals carved with grappling lions and foliage that still crisp after nine centuries. Concerts here in July and August sell out fast; book online or risk sitting on the wall outside where the acoustics are, frustratingly, almost as good. Entry is €5, cash only, and the ticket desk closes for lunch between 13:30 and 15:00 – an interval the guardian enforces with monastic certainty.

Adjacent, the former abbot’s palace is now municipal offices, but the ground-floor barrel vaults host temporary exhibitions. Last year it was black-and-white photographs of Tramontana wind damage; this year, traditional tools borrowed from local farmhouses. Free, and worth ten minutes while you wait for the bakery to reopen.

Walking Rings Around the Flatlands

Leave by the north gate, cross the irrigation channel, and you’re instantly among apple orchards and sunflower fields. The Empordà plain is pancake-level, so the only climbs are over stone bridges built for mules, not Strava segments. A signed loop heads west to the hamlet of Vilanova de la Muga (4 km), returns via the medieval mill of Can Caramany. The path is dirt, shadeless, and popular with cyclists who treat it like a personal velodrome; keep ears open for bell tinkles. In spring the ditches foam with wild fennel, in September the air smells of rotting figs – both better than the fertiliser weeks of February.

If you need more distance, pick up the greenway that once carried trains to Olot. The gravel is smooth, gradients negligible, and every kilometre is signed in paint that fades faster than the regional government replaces it. Carry water; the only bar between Vilabertran and Navata shuts on Tuesdays.

Where to Eat Without Coach-Tour Whiplash

Can Ventura, two doorways from the monastery ticket office, has English menus printed but keeps them under the counter unless asked. Three courses for €16: start with escudella (a hearty broth that arrives in a bowl big enough for two), follow with rabbit stew or the safe-option grilled chicken, finish with crema catalana torched to order. House wine comes from a cooperative in Capmany; light, peppery, nothing like the oak bombs of Rioja.

Thursday is market morning: one greengrocer van, one cheese stall selling goat’s milk formats wrapped in chestnut leaves. Locals treat it as social club rather than supply run; expect conversations to pause while the vendor debates last night’s football with a customer clutching a single leek. If you’re self-catering, stock up early – by 11:30 the lettuce is wilting and the baker’s wife is sweeping flour off the counter.

For anything fancier, drive the seven minutes to Figueres. Duran Hotel’s restaurant does a tasting menu that nods to El Bulli without the eye-watering bill, and they’ll pour you a chilled Empordà rosé while you decide. Just remember to book your taxi back; after 22:00 the two licensed cars get snapped up by nightclub crowds.

Festivals, Fortresses and the Dali Triangle

The Festa Major (end of August) turns the plaça into a dance floor. Sardanas start sedately at ten, morph into cover bands blasting eighties rock until the neighbours start flicking lights. Visitors are welcome but there’s no tourist gloss: bring earplugs and cash for beer tokens.

Classical buffs time trips for the Schubertíada (July). Concerts inside the cloister finish by 23:00 so the priest can lock up, then audiences spill onto plastic chairs in the square drinking cava from plastic cups. Tickets €25–€40; combine with late-night almond cake at Forn de Pa, baked specially for concert nights.

Day-trippers use Vilabertran as a decompression chamber between Dali sites. Figueres Theatre-Museum is eight minutes by car, Cadaqués thirty-five on coastal roads that tighten around every bend, Pubol castle twenty-five through sunflower corridors. The village itself offers no souvenir Dalí mugs – a relief or a disappointment, depending on your tolerance for moustache motifs.

The Catch: When Peacefulness Tips into Shutdown

August weekends bring an odd contradiction: the monastery swarms, yet every other shop pulls down its shutter at 14:00. If you arrive after lunch you’ll find nowhere to buy water until five, and the bakery cash machine – the only one – charges €2 and sometimes refuses foreign cards. Street lighting is deliberately kept dim; bring a torch or risk ankle-twisting between the cobbles.

Rain is rare but spectacular. The plain drains slowly, turning farm tracks into gluey clay that cakes shoes and bike tyres. Check the forecast if you’ve planned a cycling itinerary; Tramontana gusts can hit 100 km/h, toppling scooters and cancelling concerts without notice.

Winter is quieter still. The cloister heater struggles below 8°C, and the guardian may close early “because no one else is coming”. On the plus hand, Can Ventura lights its log fire and the three-course menu drops to €12. You’ll share the dining room with local farmers discussing olive subsidies – a soundtrack no Spotify playlist can match.

Leave before the bells strike noon if you’re heading to the coast; the road to Roses clogs with beach traffic by 12:15. But linger long enough to notice the bakery’s second batch emerging, golden and crackling, and you’ll understand why some Brits rent the same stone house every September: not for monuments ticked off years ago, but for the moment the village pauses, bread in hand, while the rest of the Costa Brava races past.