Full Article

about Palafrugell

Shopping and tourist hub with famous coves; birthplace of Josep Pla and of the habaneras.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The Sunday fish stall on Carrer de l’Església is already running low on red prawns by half past nine. A woman in front of you buys half a kilo—forty euros disappears into the apron pocket of the quayside vendor—and the queue behind her audibly winces. This is Palafrugell: close enough to the sea to charge coastal prices, yet stubbornly inland, a working town whose citizens still argue over football and politics in Catalan before the tourists wake up.

At only 64 m above sea level the place feels flat after the hair-pin road from Girona, but the Pyrenees are visible on clear days and the Tramuntana wind can whip down the valley without warning. That hybrid climate—part mountain, part Mediterranean—keeps nights cool even in July, a mercy when the Costa Brava proper is stewing under a heat dome.

Cork, chimneys and contemporary art

Between 1880 and 1960 Palafrugell lived off cork, not cod. The Museu del Suro, tucked into a former factory on Carrer Cervantes, still smells faintly of resin. One room is given over to a belt-driven lathe the size of a London bus; another displays champagne stoppers stamped for Harrods and the House of Commons. Entry is €5 and you’ll be round in 35 minutes, but the context turns every subsequent chimney you spot into a conversation piece.

Five minutes away, Can Mario’s brick stack has been repurposed again—this time by the Fundació Vila Casas to show Catalan sculpture from the 1960s onwards. The trio of Eduardo Chillidas on the roof terrace photograph beautifully against the Empordà sky; the café underneath does a decent flat-white that wouldn’t look out of place in Shoreditch, though at €3.20 it’s 30 cents cheaper.

The old centre itself is a grid of arcaded streets just wide enough for a single lorry delivering beer barrels. Plaça Nova fills with market awnings each Sunday: local hazelnuts, sun-dried tomatoes, and botifarra sausages heavy with pepper. Turn up after eleven and you will be shuffling behind British second-home owners comparing Camper sandal prices. Arrive at nine and you’ll hear the real soundtrack: butane bottles clanking onto doorsteps, shop shutters rattling up, gossip about last night’s council meeting.

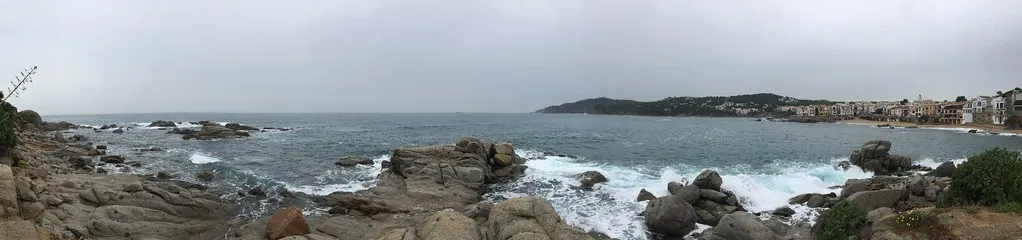

Three bays, three temperaments

Calella, Llafranc and Tamariu all fall within the municipal boundary, yet each behaves like a separate village. Calella arcs round a pair of sandy crescents sheltered by pine-topped headlands. The sea here is aquarium-clear—snorkellers follow yellow-painted rocks to the Ullastres drop-offs where grouper appear at 6 m. In August the beach is towel-to-towel by 11 a.m.; come back after six and you’ll reclaim enough space for a picnic.

Llafranc attracts the yacht crowd. The 19th-century lighthouse on Cap de Sant Sebastià hovers 160 m above, reachable by a paved path that starts behind Hotel Llafranch. Trainers are advisable: the climb is only 15 minutes but flip-flops slide on the grit. From the terrace you can spot the white wake of the Balearic ferry 20 miles out, and the café sells Estrella at airport prices—€4.50 a caña.

Tamariu, the smallest, keeps its fishing boats pulled up on the sand. The promenade is barely two metres wide; diners at the row of restaurants have to shift chairs whenever the ambulance-width road is open. Evening here feels like a film set until the coach parties from Roses depart at dusk.

Moving between worlds

No railway line reaches this coast. The realistic options are: hire a car at Girona airport (30 minutes on the C-66, €45 a week in October, triple in August) or ride the Sarfa bus from Barcelona Estació del Nord. The bus drops you in Palafrugell town; a local shuttle then winds downhill to the beaches every 30 minutes in summer, every 90 minutes off-season. Missing the 22:05 return from Calella means a €18 taxi—worth knowing if you plan a late paella.

Driving brings its own puzzle. Central Calella is residents-only from June to September; the upper car park near Cap Roig botanical gardens costs €2 an hour and is full by 11 a.m. Brits in the know leave the car there and walk ten minutes through pine shade, clutching snorkels and a bottle of frozen water.

What to eat, what to pay

Back in town, menus are printed in Catalan first, a reliable indicator of price and authenticity. Can Blau on Plaça Can Mario does a three-course lunch for €16: squid-ink rice, hake with samfaina (Catalan ratatouille), and crema catalana torched to order. Down at the coast the same bill nudges €28 before wine. Specialities to look for are suquet de peix, a saffron stew that tastes of the boat rather than the freezer, and patates braves cut into rough chunks and served with aioli sharp enough to make your sinuses tingle.

Wine lists lean towards DO Empordà: a bottle of white Garnatxa blanca runs €14-18, half the price of Rioja equivalents listed for tourists. If you’re self-catering, the Consum supermarket sells chilled rosé at €3.99 that wouldn’t shame an Oxford picnic.

When the stage lights come on

Cap Roig gardens host Spain’s longest-running outdoor music festival each July and August. Elton John, Diana Krall and, bizarrely, the Gipsy Kings have all played to 2,000 spectators with the Mediterranean flickering below. Tickets go on sale in March and the €90 seats sell out in hours; the €35 grass spaces are perfectly audible if you bring a cushion. Bring a jumper too—once the sun drops behind the pines the temperature can fall ten degrees in half an hour.

Low season has its own calendar. January brings the Festa de Sant Sebastià: a communal barbecue on Calella beach, free red wine ladled from dustbins, and a fireworks barge that drifts alarmingly close to the anchored yachts. November, by contrast, is dead; many restaurants shutter for the entire month and the coastal bus reduces to a skeleton. Visiting then is cheap—holiday lets drop to €60 a night—but you’ll need a car and a taste for solitude.

Leaving the coast behind

The Camí de Ronda footpath threads all three bays together. Heading south from Tamariu the trail climbs to pine-clad cliffs where coves appear as sudden ovals of turquoise. Cala Pedrosa, ten minutes down a stone staircase, has no facilities beyond a natural rock shelf that doubles as a sunbed; bring water and take your litter out. Northwards, the route to Llafranc passes the 15th-century watchtower Torre de Calella, built to warn of Barbary pirates—proof that overtourism is a relatively recent headache here.

Worth knowing, warts and all

Palafrugell’s double identity is its charm and its frustration. You get authentic high-street life plus the coast, but you also inherit municipal closing hours, siesta-shuttered chemists and the odd whiff of sewage when the wind turns. August crowds can feel like a squeezed tube of Factor 50; parking wardens materialise the moment your ticket expires. Yet sit on the breakwater at Llafranc one May evening, when the day-trippers have left and the lamps flick on along the promenade, and you’ll understand why half of Surrey seems to have a set of keys here. Bring a mask and snorkel, a tolerance for Catalan directness, and enough cash for those Sunday prawns—you’ll eat better, and more honestly, than anywhere on the Costa del Sol.