Full Article

about Cervera

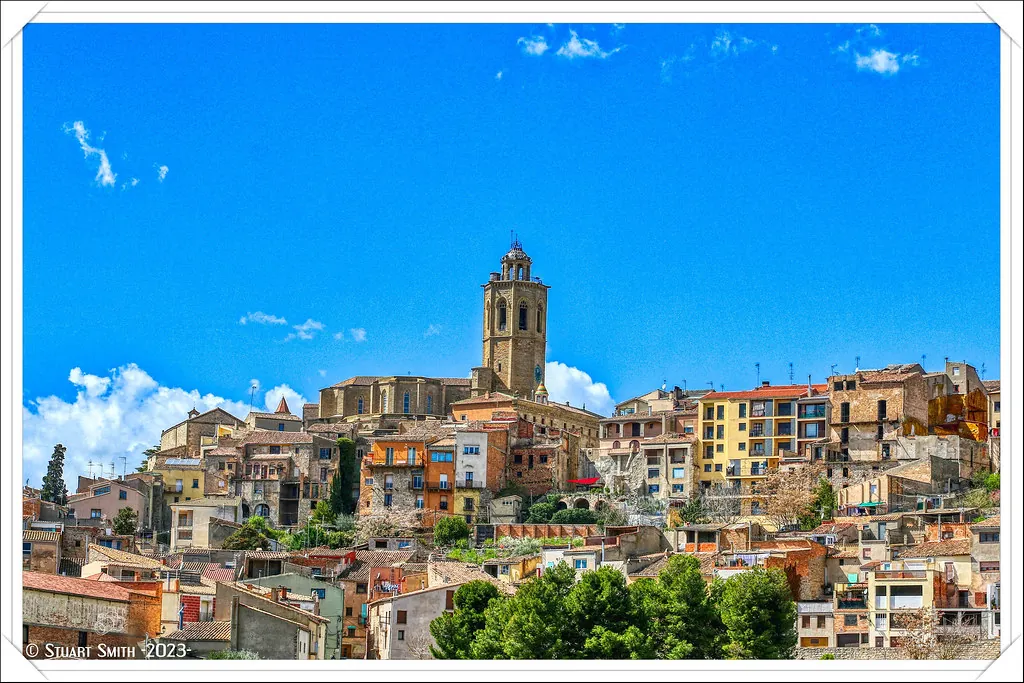

Capital of Segarra; historic university town with striking baroque and medieval heritage

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The university building stops visitors mid-stride. Not because it's beautiful—though its honey-coloured stone and parade of arches have their appeal—but because it shouldn't be here. Cervera, population under ten thousand, sits alone on its plateau with Spain's only 18th-century university outside a major city. Philip V's revenge on Barcelona for supporting the wrong side in the War of Spanish Succession created something marvellous: a full-scale seat of learning dropped into what was, and largely remains, a market town surrounded by wheat.

At 548 metres above sea level, Cervera feels higher than it sounds. The air thins, the wind picks up, and summer heat loses its edge. British visitors arriving from Barcelona's humidity notice the difference immediately—shirt sleeves that stuck to skin on the coast hang loose here. The plateau stretches east towards the Mediterranean, west towards Aragón, creating a landscape that trades postcards for practicality. Golden wheat fields roll to every horizon, interrupted only by stone farmhouses and the occasional windbreak of holm oaks. It's farming country, honest and unadorned, where the earth shows its bones.

The University That Changed Everything

The building dominates more than the skyline. Walk through the main portal and the courtyard opens like a surprise—columns three storeys high, stone staircases worn smooth by three centuries of students, and that peculiar academic hush that makes whisperers of everyone. Guided tours run twice daily (€5, English available if you email ahead) and reveal the building's working life: classrooms converted to exhibition spaces, the former assembly hall now hosting concerts, students' graffiti carved into desks when this was Catalonia's only university.

The university closed in the 1840s but never really left. Its influence shaped the town's grid, created the grand houses along Carrer Major, and established Cervera's intellectual streak that surfaces in bookshops better stocked than many provincial cities. The annual humanities festival brings speakers from Barcelona and beyond, filling cafés with animated Catalan that needs no translation—ideas sound the same in any language when properly argued over coffee.

Walking Through Medieval Arithmetic

Cervera's medieval core operates on mathematical principles. Streets narrow to the width of a single cart, then widen just enough for two donkeys to pass. The calculation was simple: maximum houses within the walls, minimum stone required for defence. What results is a rabbit warren that defeats Google Maps but rewards the lost. Turn right at the Gothic portal, left at the 14th-century hospital, and suddenly you're in a square that wasn't there a minute ago.

Santa Maria church anchors this maze with practical authority. Its octagonal tower serves as landmark and timekeeper—climb the 147 steps (€3, closed Tuesdays) and the plateau reveals its geometry. Wheat fields form golden squares, villages appear as stone cubes dropped randomly across the plain, and the Pyrenees float like a distant mirage. The view explains why this plateau attracted settlers: 360 degrees of fertile land, easily defended, with water sources in the valleys below.

The church interior tells Cervera's other story. The Gothic altarpiece survived wars, revolutions and a particularly zealous 19th-century priest who wanted it painted white. Look for the medieval tombs set into the walls—merchants who made their fortune in wheat, university professors buried near their life's work, and one stone carved with shears that marks the grave of Cervera's last master tailor. Local legend claims touching the shears brings luck to anyone seeking work—several British expats swear it helped them find teaching jobs in Barcelona.

What Grows Between the Stones

Monday morning in Cervera feels like trespassing. Shops shutter tight, bars reduce to a single table of regulars, and the only movement comes from swallows nesting under medieval eaves. Plan accordingly—this isn't a tourist town performing for visitors. The weekly market on Saturday transforms the main square into a social event where farmers discuss rainfall statistics over coffee, and grandmothers inspect tomatoes with forensic intensity. Arrive early (before 10 am) for the best selection of local cheese and cured meats, stay later for people-watching that beats any theatre.

The food reflects the landscape—robust, wheat-based, designed for workers who spent dawn-to-dusk in fields. Pa amb tomàquet appears everywhere: bread toasted over open flames, rubbed with tomato that actually tastes of tomato, drizzled with local olive oil sharp enough to make you cough. Coca de recapte, the Catalan answer to pizza, arrives on thin bases loaded with escalivada (roasted peppers and aubergine) and optional botifarra sausage. Vegetarians find plenty of options; vegans should specify no cheese—Catalan cooking defaults to dairy.

For the adventurous, game features heavily in autumn. Rabbit appears in paella, partridge stewed with wild mushrooms, and local restaurants serve what they shot yesterday. The squeamish can stick to botifarra, a mild pork sausage that tastes like improved Cumberland, or order fideuà—short noodles cooked like paella that comfort any British palate missing proper carbohydrates.

The Practical Geography of an Inland Town

Getting here requires commitment but little effort. Regional trains leave Barcelona-Sants hourly, taking 90 minutes through countryside that gradually sheds its Mediterranean character for something more continental. The €12 fare (no reservation needed) buys views of Montserrat fading behind, replaced by wheat fields that could pass for East Anglia if the hills were gentler. Renting a car? Take the A-2 motorway west for an hour, then exit at Cervera—the town appears suddenly, its university tower visible miles before the buildings.

Summer brings fierce heat despite the altitude. Temperatures hit 35°C but evenings cool to sweater weather—pack layers regardless of season. Winter surprises visitors with proper cold; frost isn't unknown, and the tramontana wind whips across the plateau with northern European bite. Spring and autumn provide the sweet spot: warm days, cool nights, and that particular light that makes wheat fields glow like something from a Constable painting.

Staying overnight reveals Cervera's best self. The two hotels occupy converted townhouses where WiFi struggles through metre-thick walls—consider it a feature, not a bug. Prices hover around €60 for a double, including breakfast that features local honey and those almond biscuits British visitors smuggle home by the kilo. The municipal albergue offers beds for €15 if you're hiking the Segarra trails that radiate from town like spokes.

Walking these paths requires preparation. The landscape offers no shade, water sources are scarce, and mobile coverage disappears in valleys. But rewards come in skylarks, ruined farmhouses that predate Shakespeare, and that profound silence unknown in Britain outside the remotest Highlands. Start early, carry water, and don't trust the estimated times on trail markers—Catalan farmers walk faster than British ramblers.

Cervera doesn't seduce; it convinces. There's no Instagram moment, no single sight that justifies the journey. Instead, it offers something increasingly rare: a Spanish town that functions for itself first, visitors second. Come for the university, stay for the conversations with shopkeepers who remember when British tourists were rare enough to comment on, and leave understanding that Catalonia extends far beyond Barcelona's tapas bars and Gaudí's mosaics. Just don't expect to leave unchanged—the plateau has a habit of staying with you, appearing in dreams as golden wheat under impossible blue skies, with a university tower rising from the middle of nowhere, exactly where it belongs.