Full Article

about Benilloba

A town with a textile tradition set in a privileged natural setting; it still has a working flour mill.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell strikes seven and nobody moves. Not because they're late, but because nobody needs to be anywhere in particular. Benilloba runs on almond blossom time, a rhythm that makes British summer evenings feel positively frantic. At 520 metres above the Costa Blanca package resorts, this tiny Comtat village operates at roughly half the speed of the coast half an hour below.

Morning Light, Mountain Air

From Alicante airport, the A-7 swerves inland at Alcoy and the CV-700 begins its climb. Sat-nav promises twenty-five minutes; reality demands forty-five of hairpins and sudden olive groves. Mobile signal flickers out around kilometre twelve – the perfect excuse to stop photographing the view and simply look at it instead. Below, the serpentine road you've just climbed resembles a dropped necklace against the valley wall.

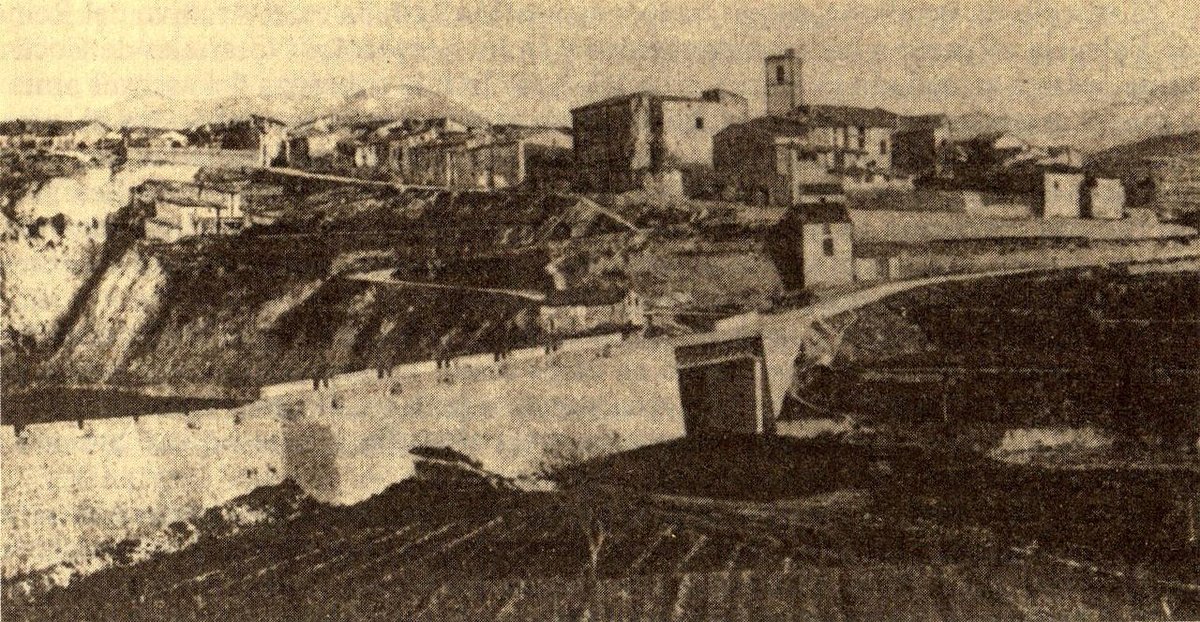

The village appears suddenly after a final bend: whitewashed houses staggered up a ridge, church tower presiding like a strict headmistress over a playground of terracotta roofs. Park where the tarmac ends; everything beyond is stone, gradient, and the occasional determined geranium. Benilloba measures barely four streets across, which means getting lost requires genuine talent.

What Passes for Action

Life centres on the Plaça de l'Església, where benches face each other like an outdoor living room. Pensioners occupy the south-facing bench at 10 am sharp, trading the same observations they've made for forty years. The north-facing bench waits for the younger crowd – meaning anyone under sixty-five – who arrive after coffee to discuss rainfall and grandchildren with equal fervour.

The Purísima Concepción church keeps Valencian rural tradition: simple stone, wooden doors painted municipal green, interior cool enough to store wine. Step inside mid-morning and you'll catch sunbeams slicing through incense haze onto worn flagstones. The priest lives next door; ring the bell if you want the place unlocked outside service times, though he's equally likely to appear carrying shopping rather than vestments.

Feeding Time

By 1:30 pm, tractors park outside Venta Nadal like horses at a saloon. The building squats on the village edge, all breeze-block and neon beer signs – exactly the sort of place British motorists drive past, unaware they're missing the best rice dish within forty kilometres. Inside, aluminium tables and paper placemats belie what's coming: arroz a banda the colour of saffron sunsets, each grain distinct yet creamy, tasting properly of fish stock rather than stock cubes. They'll swap rabbit for chicken if you ask nicely; they won't swap anything for vegetarian unless you phone ahead.

The almond cake arrives unannounced, carried by the owner's daughter who doubles as waitress and GCSE English revision expert. She practises vocabulary on willing customers, explaining that the almonds grew on slopes visible through the window. The cake itself is dense, not too sweet, and disappears faster than the mountain mist that rolls in most evenings.

Walking It Off

Afternoons belong to the caminos that spider-web across the hills. These aren't manicured National Trust paths; they're working routes between terraces, carved by centuries of mule traffic and modern tractors. Stone walls shoulder the way, sprouting fennel and wild rosemary that scent the air when brushed. The most straightforward route heads south towards the abandoned mill – forty minutes on a steady gradient that rewards with views across three valleys and, on clear days, a shimmer of Mediterranean forty kilometres distant.

Sturdier boots can tackle the PR-CV 71 which links Benilloba to neighbouring Benasau along a ridge once used by smugglers moving tobacco inland from the coast. The full circuit takes three hours, returning via the Font de la Mata spring where cold water tastes of iron and moss. Don't rely on waymarks alone; local farmers occasionally redirect paths without notifying cartographers. If the route suddenly dives through someone's vegetable patch, you've gone wrong – or right, depending on your attitude towards trespass.

When the Hills Turn White

February transforms the lower terraces into drifts of almond blossom so complete it feels like snow. Photographers arrive clutching long lenses and thermos flasks, tripods lining the cemetery wall at dawn for the classic shot: blossom foreground, terracotta village, hazy blue distance. They leave by lunchtime, missing the real show when afternoon light turns petals translucent and the entire mountain smells like marzipan.

Spring brings wild asparagus sprouting beside paths; locals carry plastic bags on morning walks, returning with dinner. Summer means proper heat – Alcoy's industrial ovens have nothing on August afternoons here when the stone radiates warmth long after sunset. That's when the village gastrobar becomes valuable; it's the only place serving after 10 pm, though calling it a gastrobar flatters what is essentially decent tapas eaten on the owner's terrace while his Labrador begs for chorizo.

The Money Question

There isn't a cash machine. The closest sits in Alcoy's main square beside a pharmacy that stocks British newspapers, creating the fortnightly ritual: coffee, Daily Telegraph, euros, back up the mountain before the heat builds. Contactless payments appear sporadically; the mini-mart installed a card reader then unplugged it when fees arrived. Bring notes, preferably small ones, and accept that buying a single lemon might clean out the till.

Accommodation choices remain limited. Casa Rural La Cirera offers the only proper pool, an above-ground affair that feels like swimming in a particularly posh water tank. The English owner leaves scones on arrival and a typed sheet explaining which restaurants tolerate children after 9 pm. Casa de les Flors costs half the price but trades pool for location: step out the door straight onto the church square, handy for Sunday morning bell practice whether you requested it or not.

Departing Thoughts

Benilloba doesn't do spectacle. It offers instead the smaller pleasures Britain mislaid somewhere between rationing and smartphones: bread that tastes of grain, conversations that meander, darkness so complete you can read by starlight. Stay three nights and shopkeepers nod recognition; stay a week and they'll ask after your family by name. The village rewards patience and punishes schedules – precisely why it's worth the winding drive.