Full Article

about La Vall de Laguar

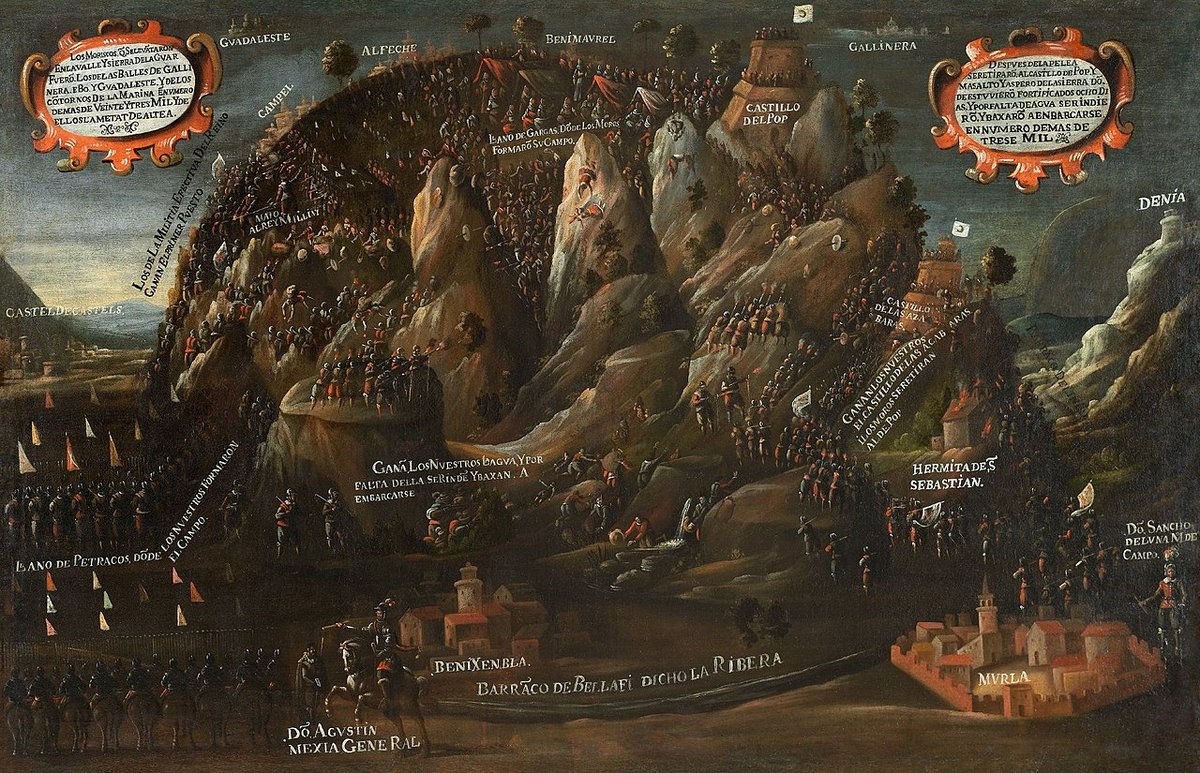

The Marina’s balcony; known for the Barranc de l'Infern and its Moorish steps

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The Valley That Turned Its Back on the Sea

From the N-332 coastal road, you can be swimming in Dénia before breakfast and still reach La Vall de Laguar in time for morning coffee. The journey takes twenty-five minutes, but the temperature drops eight degrees as you climb the serpentine CV-720. Suddenly the Mediterranean is a blue memory glimpsed between almond branches, and the soundtrack switches from crashing waves to absolute silence broken only by goat bells.

This is the western edge of the Marina Alta, where the Serra de Cavall Verd throws up a natural wall against mass tourism. Four miniature villages—Campell, Fleix, Benimaurell and Fontilles—straddle a limestone ridge at roughly 450 metres. Between them they share 873 inhabitants, two grocery shops, one cash machine and what hardened hikers call 'The Cathedral': a 14-kilometre loop known as the Barranc de l'Infern that packs 6,000 dry-stone steps into a single morning.

Stone, Water and What Happens When Both Run Out

The valley's terraced slopes are a 500-year conversation between farmers and gravity. Almond and olive trees grow out of pocket-handkerchief plots held in place by walls built without mortar; some stretch six metres high and contain more rock than soil. After heavy rain the system works perfectly, channelling every drop towards stone cisterns called aljibes. In August the same walls radiate heat like storage heaters, and the landscape turns silver-grey.

Walkers intent on the famous ravine should time their assault carefully. The circuit drops 700 metres into a natural amphitheatre before climbing straight back out, and there is no café, no water point and precious little phone signal once you leave the tarmac. Spanish weekends see upwards of 200 pairs of boots on the steps; turn up at dawn on a Tuesday and you might share the canyon only with griffon vultures. After rain the limestone becomes slick as ice—British ramblers have learned the hard way that trekking poles are not vanity accessories here.

A Menu That Knows the Price of Water

Gastronomy in the valley is dictated by altitude and thrift. Local menus change with the water table: broad-bean stew in spring, lamb roasted with rosemary when the summer streams dry up, and almond cake once the August harvest is in. El Nou Cavall Verd in Fleix will serve grilled lamb cutlets beside a vegetarian paella that tastes of rosemary smoke, while Casota in Campell offers rice dishes that require twenty-five minutes' notice because the chef refuses to re-heat stock. Neither restaurant accepts cards; the nearest cash machine is back down the mountain in Orba, so fill your wallet before you fill your stomach.

Between meals you can buy Fontilles goats' cheese from a fridge that also doubles as the village post office, or pick up a two-litre box of local olive oil for €12—roughly half the beach-resort price. The shop in Benimaurell keeps eccentric hours: open 09:00-13:00, closed for siesta, then a second shift 17:00-19:30 unless the owner decides to help with the grape harvest, in which case a handwritten sign reads "Vuelvo pronto".

When the Almonds Light the Fuse

For two weeks each February the terraces detonate into white blossom. The floración has become an unofficial festival: photographers from Alicante arrive at dawn, local beekeepers rent out hives, and British second-home owners offer "blossom breakfasts" on Instagram. The spectacle is spectacularly short-lived. A single windy night can strip the petals, and the valley returns to its default palette of green and stone before the hire cars have even cooled.

Religious festivals last longer. San Miguel in late September drags expat grandchildren back from university towns; processions start at the church in Benimaurell and finish in someone's garage with homemade mistela and a raffle for a cured ham. San Blas in Fontilles is quieter—locals queue to have their throats blessed with two crossed candles, then retreat indoors for stewed snails and aniseed liqueur. Visitors are welcomed, but there are no souvenir stalls, no printed programmes, and definitely no English commentary.

Getting Up, Getting Down, Getting Stuck

Alicante airport is ninety minutes away if the AP-7 behaves; Valencia adds another thirty. Beyond the motorway you face twelve kilometres of switchbacks: first gear, stone walls, and the unsettling realisation that oncoming buses have right of way and no reverse gear. In winter the highest bends collect cloud; August drivers wrestle with hire-car clutches that smell of burnt toast by the third hairpin. Once you're up, you're up: the valley operates a single daily bus to Alicante, and it leaves Campell at 06:45.

Accommodation is scattered across the four villages—think village houses with roof terraces rather than boutique hotels. A two-bedroom cottage with log burner and valley views rents for €80-€120 per night outside peak blossom weekends. Most owners live in Gandía or Dénia and meet guests with keys and a welcome pack that includes walking notes, emergency numbers and the universal warning: "Start the Barranc early, take more water than you think, and don't rely on Google Maps."

The Catch in the Silence

There is a trade-off for the quiet nights and star-splattered skies. Mobile coverage is patchy even in the villages; streaming a film means driving to the petrol station outside Pego for 4G. When the levante wind howls up the Ebro valley, the temperature can plunge ten degrees in an hour, and the almond blossom becomes horizontal sleet. In July the same wind feels like someone pointing a hair-dryer at your face, and the stone walls radiate heat long after sunset.

Yet for every British walker who curses the 06:00 alarm, another books the same house for the same week next year. They come for the moment the ravine falls silent, for goat cheese eaten under a carob tree, for the realisation that the Mediterranean is twenty-five minutes away but might as well be on another planet. Just remember to fill the hire-car tank before you climb, download the walking route offline, and bring cash for the lamb. The valley will supply the rest—provided you arrive before the blossom blows away.