Full Article

about Coria

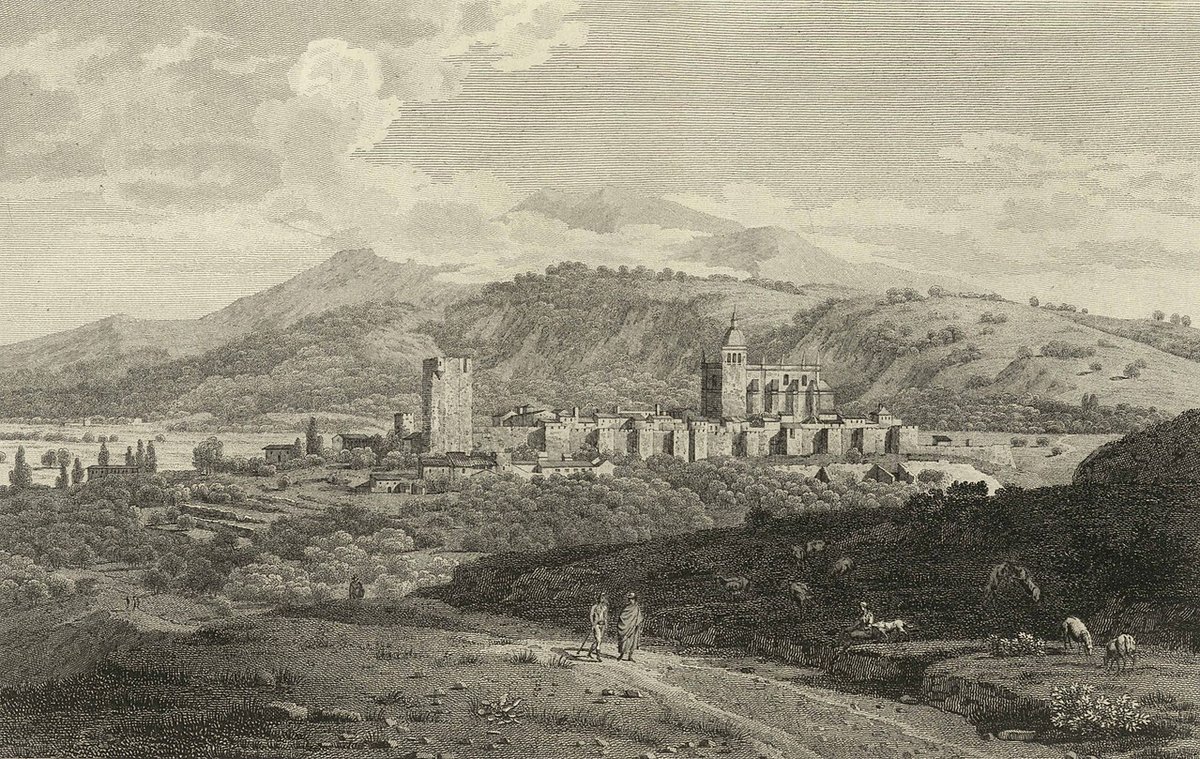

Ancient Roman and episcopal city with intact walls and a cathedral overlooking the Alagón river

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

At 7.30 on a Tuesday morning the bells of Santa María de la Asunción bounce off granite walls loud enough to drown the clatter of the first coffee cups. Shopkeepers roll up shutters, schoolchildren cut across Plaza de San Pedro, and the smell of toasting breadcrumbs drifts from a bar that has no name—just a hand-painted sign that reads “Café y Migas”. This is Coria’s daily overture: small-city Extremadura in real time, neither hidden nor hyped, 212 km west of Madrid and a whisker above the Portuguese border.

A Town that Forgot to Modernise its Walls

Roman engineers started the ramparts; medieval bishops raised them; today they work as a circular balcony. From any surviving stretch—Puerta de San Pedro is the easiest—you look down over the Alagón river plain, a chessboard of allotment plots edged by poplars. Inside the loop the streets are barely two cars wide, so narrow that neighbours on opposite balconies could swap newspapers without leaning too far. Parking is wink-and-pray, but once you’ve dumped the hire car in the free riverside carpark (signposted Aparcamiento Alagón, GPS 39.9861, -6.5417) you won’t need it again.

The cathedral claims the skyline with an eighteenth-century tower that still wears the original ochre plaster—no Disney-white restoration here. Inside, the baroque high altar is a riot of twisted columns and gilt that feels almost Mexican; the side chapel keeps a Flemish triptych looted, local legend says, from a ship bound for Seville. Entry is €3 and includes the small cloister museum where a Roman mosaic of Venus shares floor space with gold monstrances. Doors stay open 10-13 & 17-19, except Monday when the staff simply don’t.

Opposite, the semi-ruined Castillo de los Duques de Alba is fenced off for safety, yet the town has installed a neat steel gantry so you can peer into the keep and photograph the nesting storks for free. Evening light turns the stone tangerine; cameras love it, and you’ll probably share the parapet only with an elderly man walking his hunting dog.

River, Garden, Table

Step through any gate in the walls and you drop within three minutes onto the vega, the irrigated flood-plain that earns Coria its tag “the vegetable garden of Extremadura”. Concrete irrigation ditches still run like Roman aqueducts; allotments grow tomatoes the size of cricket balls and peppers that end up hanging in strings outside village houses to dry. A flat 5 km circuit follows the river south to the ruined convent of Madre de Dios and back—no boots required, just shoes you don’t mind dusty. Kingfishers flash turquoise under the poplars; farmers shout “¡Buen camino!” from tractors that look older than the Queen.

Back inside the walls, lunch is serious business and clocks shift to siesta time. Locals recommend Asador El Fogón de Gómez for a chuletón de Ávila—an on-the-bone rib for two that arrives sizzling and costs €32 per person with potatoes and house red. If that sounds like cardiac arrest, Bar Rincón de la Catedral does a lighter tortilla del Alagón stuffed with smoked trout from the river, still €9 even after the tourists (all six of them) discovered it. Finish with a sliver of Torta del Casar, the local sheeps’-milk cheese that liquefies into a pungent puddle—think Brie that’s been to the gym.

Bear in mind the Extremaduran midday shutdown: kitchens close at 14:30 sharp. Arrive at 15:00 and you’ll be offered crisps and a lukewarm beer until evening service starts around 20:30. Saturday is market day in Plaza de la Constitución—cheap figs, hand-chorizo, and plastic bags full of saffron at half the UK price.

Fiestas, Fireworks and Fighting Bulls

Coria’s calendar revolves around the Sanjuanes, the week around 24 June. Streets are strung with paper lanterns, brass bands march at 02:00, and novices sprint in front of half-tonne bulls through the very alleys you strolled peacefully in May. Accommodation triples; some guest-houses demand a four-night minimum. If you fancy witnessing Spain’s oldest surviving encierro outside Pamplona, book in February. If not, treat late June like the plague—unless you enjoy drum-beats until dawn and bars that run out of lager by lunchtime.

The rest of the year the town reverts to its default setting: quiet, Catholic, and slightly bemused by outsiders. British motor-homers praise the riverside carpark for its free toilets and nightly police patrols; walkers on the Camino Plata drop by for the cheap municipal albergue (€10, open Easter to October). Everyone remarks on the same thing: no souvenir tat, no Irish bars, no bilingual menus—just Spain getting on with life.

Getting There, Getting In, Getting Stuck

Coria sits on the EX-390, a winding but decent road that links the A-66 motorway (Salamanca–Seville) with the Portuguese border at Vilar Formoso. From Seville it’s 2 h 45 min; from Madrid 3 h on the A-5 then country roads. There is no train. ALSA runs one daily bus from Madrid’s Estación Sur at 08:00, arriving 12:15—comfortable, half-empty, €22. Inside town everything is walkable, though cobbles punish wheeled suitcases.

Where to sleep? The pick is the three-star NH Ciudad de Coria, built into the walls with a roof terrace that frames the cathedral tower perfectly. Doubles from €70 shoulder season, breakfast €9 extra. Budget option: Hostal Alagón opposite the river park, spotless rooms at €35, though you’ll hear early-morning dog-walkers. Note that most old-town houses lack air-conditioning; July and August regularly hit 40 °C. Spring and autumn sit comfortably at 24 °C, ideal for wall-walking and river-path loafing.

When the Bells Ring Again

Leave after breakfast and Coria can feel like a film set waiting for actors who never arrive. Stay until the second bell cycle and you realise the set is alive: lawyers dash to the town hall, teenagers swap earphones outside the convent school, and the barman who served your coffee counts the copper coins twice because he still trusts the weight of money. It is not spectacular, and that is precisely the point. One British visitor stopped for petrol, lingered for the cathedral, and wrote in the guest-book: “Found the Spain I thought had disappeared in 1975.” If you measure travel by checklists, keep driving. If you measure it by rhythm, Coria will slow your pulse to river time—and you may find yourself still on the terrace when the bells strike again.