Full Article

about Ribeira

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

Dawn smells of diesel and sardines

At six-thirty the harbour lights are still on, but the diesel throb of the first trawler heading out drowns the sodium hum. Nets clatter, gulls wheel overhead, and the air carries a blunt cocktail of salt, two-stroke oil, and yesterday’s fish guts. This is Ribeira’s morning handshake: no rose-tinted postcards, just a port that earns its keep. By nine the same boats glide back in, crates of velvet crab and razor clams swung straight on to the quay where auction staff rattle off prices in rapid Galician. Visitors are welcome to watch; stand near the weighing scales and you’ll feel the spray on your face and probably on your jacket – bring the waterproof you packed for “just in case” Galician weather.

The town itself stretches along the inner shore of the Ría de Arousa, low-lying and practical. Concrete apartment blocks rise behind the promenade, painted in colours that once might have been cheerful. Uphill, narrow lanes hide small squares where elderly men shuffle dominoes and the coffee costs €1.20 if you order it at the counter like a local. Tourism exists, but it’s a side job; the real business is the sea.

Beaches for every wind direction

Ribeira’s coast is a string of scalloped bays, each facing a slightly different compass point so locals can pick a lee shore when the Atlantic picks a fight. Playa de Coroso, a ten-minute walk west of the port wall, is the easiest all-rounder: generous curve of pale sand, bins emptied daily, and a beach bar that opens only when the thermometer edges past 20 °C. At weekends Spanish families arrive with cool-boxes the size of washing machines; turn up before eleven and you’ll still find space to spread a towel.

If the northerly wind is whipping up sandstorms, drive five minutes south to Vilar, tucked behind a headland and sheltered by pines. The water clarity here surprises first-timers – a translucent green more Caribbean than Celtic – though the temperature remains stubbornly North Atlantic. Castiñeiras, another three kilometres on, offers the widest horizon and the strongest waves; surfers check it first, sunbathers retreat to Coroso if it’s blowing hard. None of the beaches charge for entry or parking outside August, when a hopeful attendant may levy €2 for “security”.

Dunes that shift while you watch

Fifteen kilometres south-west, the Corrubedo Natural Park feels like someone dropped a slice of the Sahara beside the ocean. Mobile dunes migrate eastwards each year, burying pine trunks and footpaths faster than the park rangers can remap them. A wooden boardwalk gives a ten-minute route to the summit, but the better plan is to park at the southern end and follow the shoreline trail: on one side Atlantic rollers slam the rocks, on the other freshwater lagoons mirror the sky. Flamingos occasionally drop in during autumn migration – a surreal sight when you left grey Britain that morning.

The lighthouse at Cabo Falcoeiro stands on solid granite, though everything around it drifts. Climb the outside steps for a full 270-degree vista: to the north the ría scatters mussel rafts like a giant connect-the-dots game; west, nothing but open ocean until Newfoundland. On blowy days (most days) hold the rail; gusts exceeding 70 km/h have been recorded in June, sending baseball caps into the drink.

Lunch follows the auction clock

Fish is sold by 10.30; by 11.30 it’s on a plate. In the harbour-side cafés order what the crews are eating: caldeirada, a saffron-stained stew of monkfish and potatoes, or a plate of zamburiñas – small scallops gratinaded with breadcrumbs and parsley. Pulpo a feira arrives on a wooden platter, the octopus snipped into bite-sized pieces with scissors kept specifically for the job. Sprinkle the paprika yourself; too much and you’ll sneeze, too little and the chef assumes you don’t know flavour. Prices are lower than Santiago’s tourist traps: expect €12–14 for a main, wine included. Menus are Galician-castellano only; pointing works, but learning “un pouquiño máis” (a tiny bit more) earns approving nods.

If you self-cater, the covered market (open till 13.30) sells empanada by weight. Choose the tuna-and-pepper slab, room temperature and sturdy enough for a hike. Pair it with a €3 bottle of local Albariño and you’ve got a picnic fit for the dunes – just pack out the foil because coastal bins overflow on summer Sundays.

Walking off the salt

Ribeira sits at sea level but the Barbanza hills rise immediately behind. A way-marked path leaves from the cemetery gate, climbing 350 m through gorse and eucalyptus to the Mirador de A Curota. The ascent takes ninety minutes, shade is scarce, but the payoff is a crow’s-nest view over the entire ría. On clear winter days you can count five river mouths and the distant tower of Santiago’s cathedral, 40 km away. Bring layers; Galicia’s micro-climate means sunshine on the beach and cloud on the ridge appearing within the same hour.

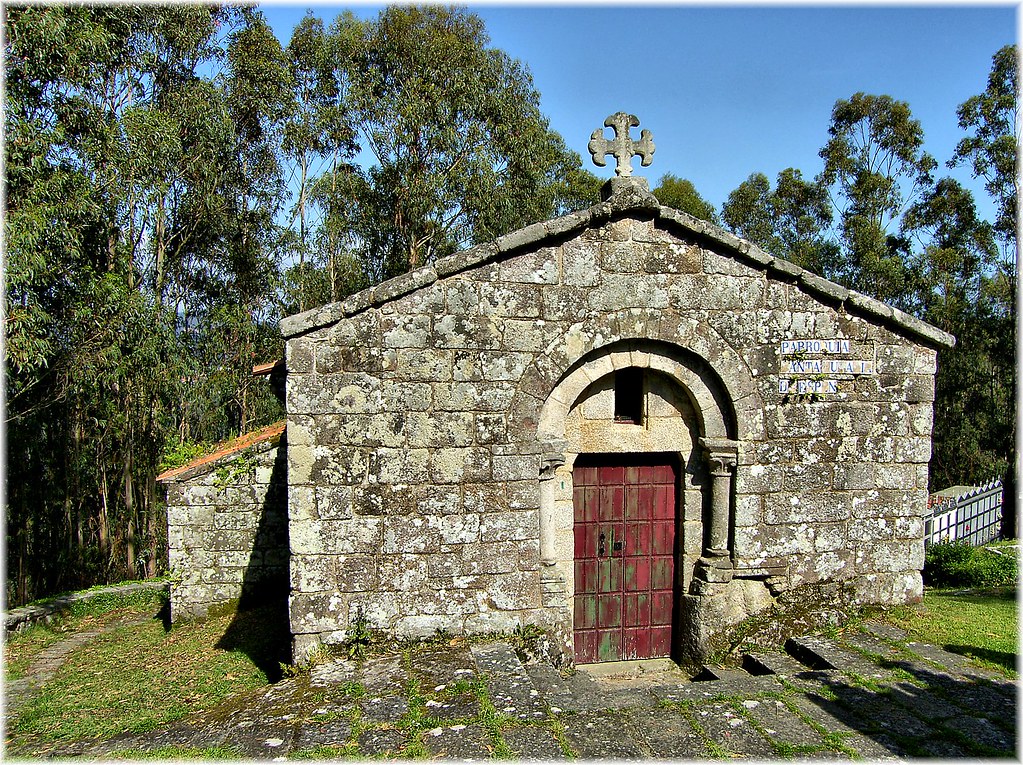

Coastal hikes are gentler. A six-kilometre route links Coroso to the Romanesque chapel of Nosa Señora do Camiño, passing abandoned grape terraces and stone walls laced with wild fennel. The trail is signed but narrow; after rain it turns into a shallow stream. Proper footwear, not flip-flops, is advised.

When to come, when to stay away

Spring brings wild irises and empty beaches; daytime temperatures hover around 17 °C, cool enough for walking, warm enough to sit outside with coffee. Autumn (mid-September to mid-October) is quieter still, and the Festa do Marisco shells out platter after platter of discounted seafood. Accommodation prices drop to €45 for a harbour-view double, half the August rate.

Avoid 15–31 July if you dislike crowds. The Festas do Carmen fills every guest-house, parade brass bands march until 3 a.m., and car parks become grid-locked. Likewise the last fortnight of August, when Madrid families migrate north and the town’s population effectively doubles. If those are your only dates, book early and expect noise.

Practical shards

Fly to Santiago de Compostela; Arriva bus 6A departs hourly, costs €8.10 single, and deposits you opposite the tourist office in 1 h 45 m. Car hire unlocks the region: the Axeitos dolmen, a 4,000-year-old burial chamber, is twenty minutes away and usually deserted. Roads are empty outside peak season; fuel runs cheaper than UK motorway prices.

Cash remains useful. Many bars refuse cards for orders under €10, and harbour-side ATMs sometimes run dry on Fridays. English is patchy; learn “bos días” (good morning) and staff soften instantly. Finally, pack the lightweight raincoat even in July; when Atlantic clouds roll in you’ll be grateful, and you can spot the Brits who assumed Spain equals sunshine – they’re the ones buying €20 umbrellas in the souvenir kiosk.

Ribeira offers no fairy-tale old quarter, no cocktail bars on rooftops. What it does offer is Galicia unfiltered: salt on your lips, octopus with the right amount of paprika, and dunes that might have shifted before you return tomorrow. Turn up curious, not expectant, and the Atlantic will organise the rest.