Full Article

about Ribadavia

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

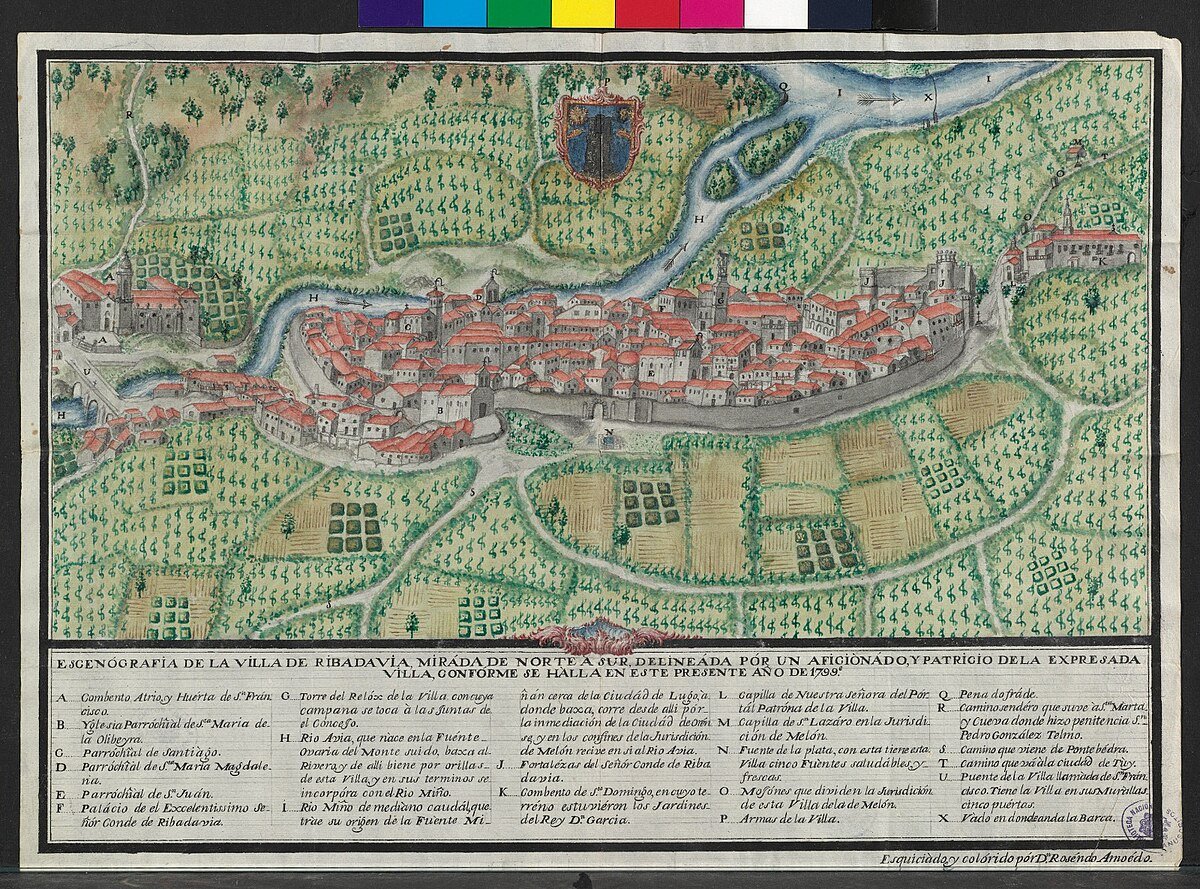

The first thing you notice is the sound of water. Not the crash of surf Galicia is famous for, but the steady murmur of the Avia river sliding into the Miño, wrapping Ribadavia in cool air even when the valley vineyards are sweating under a September sun. At 120 m above sea level the town sits low for Galicia, yet the hills climb immediately behind it; walk ten minutes up the cobbled lanes and you’re looking down on a terracotta roofscape that hasn’t changed much since the Sarmiento family ran the place in the fifteenth century.

That vantage point is the ruined Castillo de los Sarmiento, more wall than castle these days. The climb takes fifteen minutes if you refuse to pause; most people take thirty, distracted by the way the granite changes colour as the light moves. From the top you can trace the old Jewish quarter’s alleyways—narrow enough to touch both sides if you’ve got long arms—and see why the town grew here: rivers for transport, south-facing slopes for ripening grapes, and a ridge for keeping an eye on neighbours who were usually armed.

Down in the streets the air smells of must at harvest time, even when the wineries are half a mile away. Ribadavia is the informal capital of D.O. Ribeiro, the wine region that supplied medieval England before Sherry stole the limelight. The whites—mainly Treixadura with a dash of Albariño—are lighter than those from the coast, served in shallow ceramic cuncas that look like soup bowls and spill easily after the third refill. Several bars still keep barrels behind the counter; you hand over two euros, they pull the tap, you write your name on the blackboard. No tasting notes, no ceremony, just wine that costs less than bottled water back home.

If you want labels and stainless-steel tanks, head to Pazo Lodeiro (signposted off the N-525). Ring a day ahead and someone will talk you through fermentation temperatures in fluent if eccentric English. The visit is free, the wine cheaper at the gate than in London’s Oddbins, and the view from the fermentation room—rows of vines rolling east towards the railway—explains why trains slow down here even when there’s no station.

The Jewish quarter is less about individual sights than about feel. After the expulsion of 1492 the synagogue vanished; look instead for small brass plaques set into the pavement showing a menorah and the outline of the old street pattern. The Centro de Información Xudía de Galicia on Rúa Xudíos opens erratically—Tuesday morning if you’re lucky, closed for lunch regardless—so treat it as a bonus rather than the main event. What survives is scale: doorways barely five foot six, lanes that turn ninety degrees for no obvious reason, and the occasional Star of David carved above a cellar window now used for storing deckchairs.

Praza Maior works as the natural meeting point. Arcaded on three sides, it fills with older men in flat caps at eleven and again at seven, arguing over the price of grapes while their wives queue for bread at Panadería Molina. Order a cortado at Café Moderno (Art-Deco frontage, 1928) and you can eavesdrop even if your Galician is limited; body language translates. On Saturdays a small market spreads across the top of the square: plastic bowls of peppers, bunches of coriander the size of bridal bouquets, and empanada gallega sold by the wedge. Octopus and paprika is the classic, but the tuna-and-egg version travels better if you’re planning a picnic up at the castle.

Beyond wine and stone, Ribadavia’s other speciality is water. A five-minute riverside path follows the Avia upstream past washing posts once used by convents. The route is flat, shaded by alders, and mercifully free of the cyclists who thunder along the Miño further north. After heavy rain the path floods; locals post updates on a hand-written board by the medieval bridge, so check before you set off with camera and sandwiches. If the river behaves, you can walk forty minutes to the Romanesque church at Pesqueiras, have a beer, and hitch a taxi back for €10.

Come the first weekend of August the town rewinds five centuries. The Festa da Istoria dresses every inhabitant—babies, dogs, the mayor—in medieval gear, issues a currency called the maravedí, and stages a banquet on long tables in Praza Maior. Tickets for the feast sell out in March; without one you’ll still get roaming minstrels, street theatre and a nightly sound-and-light show projected onto the castle walls. Accommodation triples in price and halves in availability; book early or stay in nearby Ourense and drive (30 min on the fast road).

Outside fiesta time evenings are quiet. Youngsters migrate to industrial estates outside Ourense, leaving Ribadavia to the scent of wood smoke and the clink of cuncas. British visitors sometimes panic at the silence, then discover it’s the perfect setting for a long conversation with a glass of something local. Night-life is what you make it: a bottle of Ribeiro, a bench under the plane trees, and a sky dark enough to see the Milky Way once the square lights dim at 01:00.

Practicalities are straightforward. Fly to Porto (two hours from Gatwick, Manchester or Bristol) and hire a car; the drive northeast is 90 minutes on toll-free motorways. Vigo is nearer (60 min) but flights are summer-only and pricier. Santiago de Compostela works too, though you’ll skirt three other wine regions before you reach Ribadavia—dangerous for drivers who taste first and calculate units later. Park on the signposted ring road; the old centre is pedestrian and small enough that you’ll never be more than five minutes from the car.

Stay inside the medieval loop if you can. Hotel Parada de Sil occupies a sixteenth-century mansion on Rúa San Francisco; rooms start at €85 including a cellar breakfast among stone vaults. Budget alternatives cluster south of the river, clean but functional, best for travellers who plan to spend daylight among vines rather than in a robe. Sunday night is the secret bargain: weekend visitors dash back to Madrid, hotels drop rates, and Monday morning gives you shuttered streets to photograph without a human in sight.

Weather behaves like Cornwall with Spanish timing. April and May bring morning mist that burns off by eleven; temperatures hover around 20 °C, ideal for walking the vineyard tracks. September light is softer, leaves turning copper, harvest lorries blocking lanes as they crawl to the cooperative. Mid-winter is damp rather than cold—daytime 10 °C—but the greens fade to khaki and many bodegas close for cleaning. July and August hit 35 °C; stone walls radiate heat until midnight, so follow the local siesta rhythm and reappear at six when shadows stretch across the cobbles.

Leave space in the suitcase. A five-litre garrafa of Ribeiro won’t survive Ryanair hand-luggage rules, but 75 cl bottles fit snugly and customs allow six per person. Almond cake keeps for a week if the sponge survives the journey; Herminia’s biscuits, heavy with cardamom, disappear faster than duty-free Toblerone. And if you forget everything else, remember the phrase “Outro cunca, por favor”—the gateway to a second bowl of wine and the surest sign you’ve stopped travelling and arrived.