Full Article

about Leiva

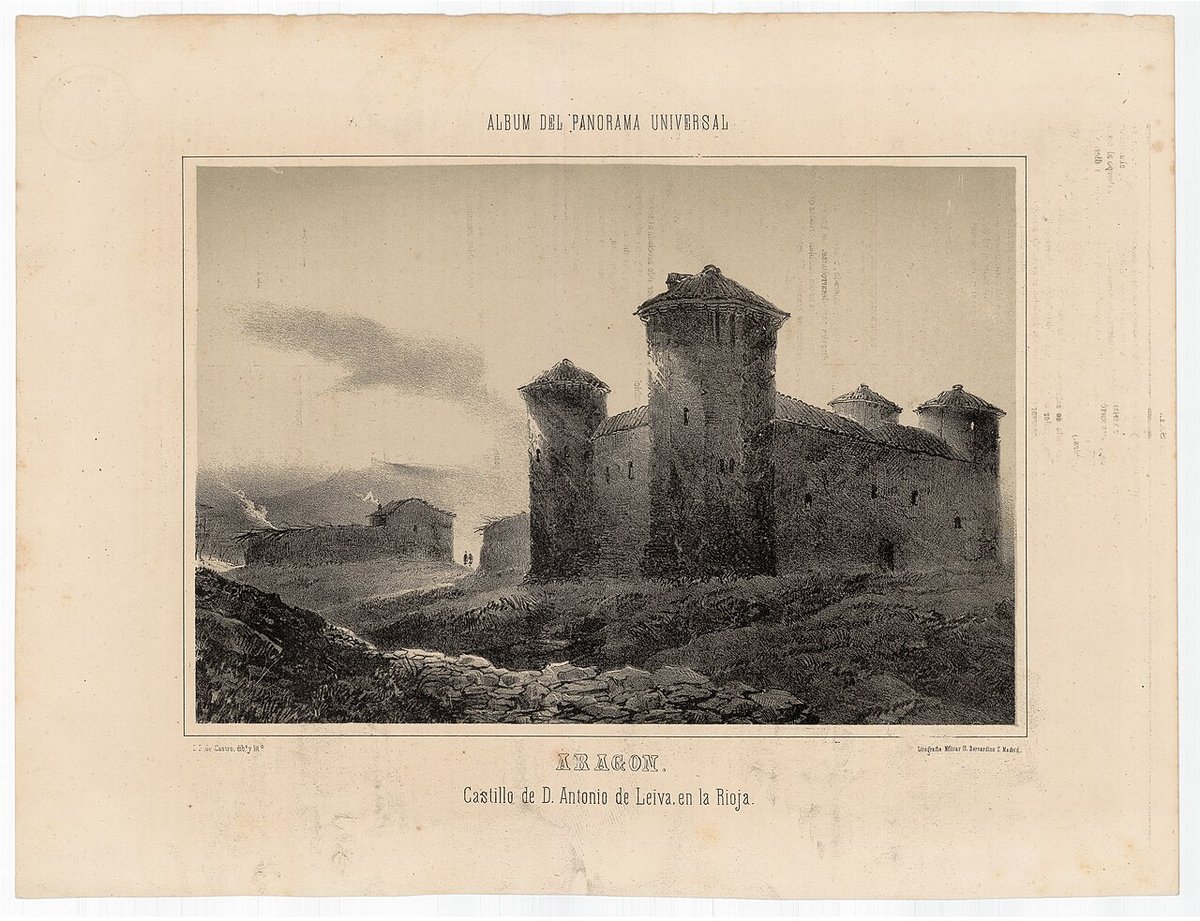

Town dominated by an impressive castle-palace; set beside the Tirón river and its reservoir.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell in Leiva tolls twice. No one hurries. A tractor idles outside the only bar, its driver sipping a cortado while the morning sun creeps across stone doorways carved in 1687. Somewhere behind the houses, a covey of quail clatters out of the cereal stubble. You are 580 metres above sea level on the southern lip of the Toloño range, and the silence feels almost mischievous – the sort that makes a Londoner check their phone for signal that, frankly, was never there.

A place that forgot to grow

Leiva’s population hovers around 245, a figure that has been shrinking since the railway bypassed it in the nineteenth century. What remains is a grid of five streets, two plazas and more wine presses per head than seems statistically possible. Houses are built from honey-coloured sandstone quarried ten kilometres away; the stone drinks in dawn light and releases it slowly, so the whole village glows for an hour after sunrise. Notice the carved escutcheons above doorways – lions, stars and, on one lintel, a relief of grapes the size of cricket balls. They hint at fortunes made when Rioja was shipped downriver to Bilbao and on to Brighton, long before British supermarkets discovered tempranillo.

There is no souvenir shop, no cash machine, no boutique hotel. The nearest traffic light is in Haro, 14 kilometres north-west. That absence of infrastructure is either a warning or a promise, depending on what you expect from holiday accommodation. Mobile data flickers between one bar and “SOS only”; Vodafone users generally fare better than EE. Bring coins for coffee – contactless works inside La Terraza, but only on days when the router remembers its own password.

Walking into the past, and the pasture

The GR-1 long-distance path skirts the village after descending from the ruined monastery of San Millán. Way-markers consist of a white stripe above a yellow one, painted on power poles and the occasional sheep trough. Follow them west and you drop into the Ea valley, where storks nest on electricity pylons and farmers still bind hay with twine instead of plastic. The round trip to the Romanesque hermitage of Santa Lucía takes ninety minutes; allow longer if you stop to photograph the terraces of garnacha tinta that glow like stained glass in October.

Serious walkers can stitch together a 17-kilometre circuit over the Toloño ridge and down to Villalba de Rioja. The climb gains 400 metres through Holm oak and kermes scrub; in April the understory is white with Solomon’s seal. Snow falls here just often enough to be inconvenient – February paths can be icy until eleven o’clock, after which the mud takes over. Stout footwear is non-negotiable; one misplaced boot in a ploughed field will add three kilos to each foot.

Cyclists arrive with gravel bikes, tempted by the disused mining railway that has been resurfaced as a greenway. The track runs 35 kilometres south to Arnedo, passing through two tunnels long enough to require lights. Bike hire is possible in Haro (Ciclos Hiniesta, €25 a day), but you will need a car rack or a very understanding taxi driver to reach Leiva with the bicycle in tow.

What you’ll eat – and when you won’t

La Terraza opens at eight for coffee and churros on market days (Tuesday and Friday). By one o’clock the television in the corner has switched to the lunchtime news and the single waiter is balancing three plates of patatas a la riojana, the region’s paprika-spiked potato stew. A menú del día costs €14 and includes wine that arrived in a five-litre plastic jug from the cooperative down the road. Vegetarians can ask for the stew without chorizo; vegans should probably keep walking. If you need dinner after nine, phone the tourist apartments before noon and they’ll leave a lamb chop in the oven – otherwise it’s a 15-minute drive to Azofra where two competing asadores will argue over who grills the better chuletón.

Self-caterers should stock up in Santo Domingo de la Calzada: the village shop in Leiva is the size of a London kitchen and closes for siesta at 13:30, reopening only when the owner has finished feeding her chickens. Sunday afternoons it stays shut altogether. Forgotten essentials – oat milk, hummus, anything resembling a fresh chilli – require a 40-minute round trip to the Eroski supermarket on the Haro ring road.

Seasons that change the deal

May turns the surrounding fields into a chessboard of green wheat and black netted vines. Temperatures sit in the low twenties; nightingales sing until midnight and locals complain if the thermometer drops below 12 °C. By July the plateau radiates heat; walkers set out at dawn and hide indoors between two and five o’clock. Only harvest workers move at midday, their faces wrapped against the reflected glare of limestone soil. Accommodation prices do not budge – Leiva is too small for dynamic pricing – but you may find every room taken during the Haro Wine Battle (29 June), when thousands of locals spray each other with 50,000 litres of red wine and sleep it off wherever they can.

Autumn is the photographers’ favourite. Morning mist pools in the Ea valley, lifting to reveal rows of maples turning copper on the higher ground. The grape harvest begins at first light, headlights of tractors forming constellations across the slopes. Visitors are welcome to join in – payment consists of a bocadillo at ten and all the grapes you can eat, provided you resist the urge to photograph workers who would rather not appear on Instagram.

Winter strips the landscape to bone and sinew. When the cidra wind blows from the north, snow can dust the vines within an hour; roads become glassy and the village water supply occasionally freezes. On those days the bar serves coffee by candlelight and conversation turns to the winter of 2021 when drifts reached the first-floor windows. Still, the sun often returns by lunchtime, turning icicles into chandeliers above the church portal. If you crave certainty, book a four-wheel-drive or stick to March.

Getting here, and away again

No railway station, no bus at weekends. The weekday school service leaves Haro at 07:45 and returns at 14:00; visitors are tolerated provided they do not try to pay with a €20 note. A pre-booked taxi from Santo Domingo costs €20 and the driver will phone your accommodation to confirm someone is expecting you. From Bilbao airport, allow 90 minutes by hire car: take the A-68 south, exit at Haro, then follow the LR-404 for twelve minutes past fields that smell of fennel when the sun hits them. Petrol is usually two cents cheaper at the unmanned station in nearby Cihuri – worth knowing if you are running on fumes and pride.

Leaving presents the same puzzle in reverse. Mobile signal is weakest in the village centre; walk uphill towards the cemetery if you need to summon Uber – although the nearest driver will probably be in Logroño, half an hour away. Most visitors simply retrace their route to Haro, stock up on wine at the Bodegas Muga shop, and join the motorway south before the siesta ends and the lorries reclaim the road.

Leiva will not change your life. It may, for a morning, slow your pulse to match the pace of a place where traffic jams involve sheep and the loudest sound is the clink of a coffee cup on zinc. Arrive with a full tank, an offline map and no expectation of souvenir fridge magnets. Leave before you need toothpaste – or stay long enough to learn which field path leads to the ridge where vultures circle on thermals above the vines. Either way, the village will still be there when the wine battle is over, doing what it has always done: growing grapes, ringing the church bell twice, and pretending the twenty-first century was merely a passing rumour.