Full Article

about Agoncillo

A town near the capital that hosts the airport and a striking medieval castle; it blends industry with historic heritage.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The first thing that strikes you is the horizon. From the apron of Logroño-Agoncillo airport the land drops away so gently that the Ebro, only three kilometres off, is invisible; instead you see a chequerboard of vegetable plots, trellised vines and the white dots of greenhouses glinting like polytunnel snow. Most passengers stampede straight for the car-rental desk and bomb up the N-232 to Logroño, but if you turn left instead of right you reach Agoncillo proper in six minutes. The speed limit is 50 km/h; a tractor will remind you why.

A village that refuses to pose

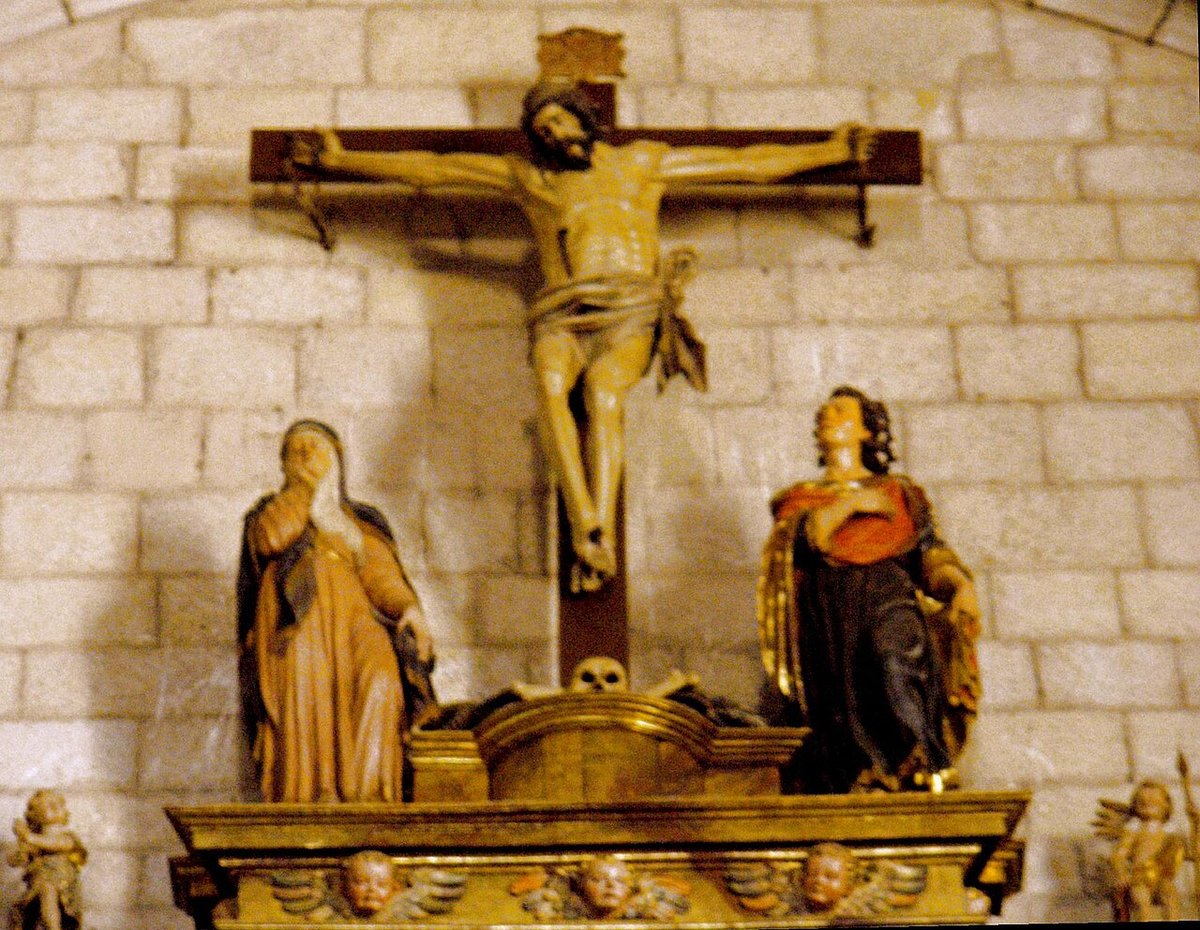

Agoncillo’s high street is called, matter-of-factly, Calle Mayor. There are no flower-decked balconies timed to bloom for Instagram, just dusty plane trees, a pharmacy with a 1980s sun-blind and locals who park on the pavement because they always have. The 16th-century church of San Esteban squats at the top of the hill – stone the colour of burnt cream, a tower you can circumnavigate in 90 seconds. The door is usually locked; ring the bell taped to the presbytery wall and the sacristan may appear, wiping his hands on a tea towel, to let you into a single nave lined with gilt that has darkened to the shade of old tobacco. No charge, but a €2 coin in the box keeps the lights on long enough to notice the 18th-century panel of Saint Blaise holding a model of the village that still fits inside your palm.

Five minutes downhill is the Würth Museum, the real surprise. A titanium-grey box designed by architects Ábalos & Herreros sits opposite the municipal sports court where teenagers slam footballs against a wall plastered with a faded advert for Rioja wine. Inside, the collection is ruthlessly good: a three-metre Manolo Valdés wooden head, Richard Deacon’s twisted steel verbs, a whole room of cybernetic sculptures that twitch when you breathe. Admission is free; the guard follows you at a polite distance and will switch on the video installations if you linger. Tuesday to Sunday only, 11-14:00 and 17-20:00. Close on Monday – the Spanish day of rest for culture.

Lunch, siesta and the art of the chuletón

By 13:30 the bars along Calle Mayor fill with men in work boots drinking short glasses of clarete, the local rosé that sits somewhere between a pale red and a dark pink. Order it by the word, not the colour: “un clarete” gets you 200 ml for €1.80. Food is grilled, not fussed over. At Asador Chusmi the chuletón for two arrives on a pewter plate, a T-bone the width of a laptop, cooked only on the outside and carved at the table so the blood pools with the rock salt. Chips come separately in a wicker basket; ask for “verduras” and you’ll receive whatever the huerta delivered that morning – perhaps piquillo peppers, perhaps cardoons in ham broth. Cards are accepted, but the terminal is under the counter; cash is faster and the waitstaff visibly relax when you produce it.

After lunch the village shuts. Not metaphorically – metal shutters crash down, even the bakery locks up, and the only sound is the click of the traffic lights changing for non-existent traffic. Plan accordingly: fill the hire-car with petrol on Saturday evening, buy emergency crisps, and accept that between 14:00 and 17:00 you are on your own. The castle ruin of Aguas Mansas, ten minutes on foot, is best visited in this interval; no guides, no ropes, just a crumbling keep where storks have built nests the size of satellite dishes. The view stretches south to the river and north to the Cantabrian foothills, still snow-dusted in April.

River, reeds and the wrong shoes

Agoncillo sits 350 metres above sea level, low enough for soft winters but high enough that the Ebro can trap cold air in the valley. The result is a morning fog that smells of damp poplar and diesel from the tractors warming up. Three way-marked trails leave from the southern edge of town; the shortest, Senda de la Vega, is a flat 4 km loop between irrigation ditches where herons stand motionless like grey umbrellas. After heavy rain the clay sticks to trainers like wet cement – proper footwear saves half an hour of inelegant scraping at the end. In July the same path is shadeless and 35 °C by 11:00; start early or wait for the 19:00 glow when the light turns the vineyards copper and the cicadas hand over to nightingales.

Serious walkers can link up with the GR-99 long-distance path that follows the Ebro from source to sea. Heading west you reach the stone Roman bridge of Calahorra in two hours; eastwards, the lagoon of Lodosa attracts spoonbills and avocets in April-May. Neither direction requires more than stout shoes and a 500 ml water bottle – the land is table-flat, the navigation idiot-proof.

When to come, when to leave

Spring brings asparagus and artichoke; autumn delivers pochas (fresh white haricots) and the first pressings of olive oil from neighbouring Navarre. Both seasons colour the riverbank in a way that feels managed by accident rather than design. August is hot, empty and inexpensive: the single three-star hotel drops to €55 a night, but the museum shortens its afternoon shift and half the restaurants close so the owners can holiday on the coast. Winter is misty, sometimes minus 2 °C at dawn, yet the light is so sharp that the Sierra de Cantabria appears close enough to walk to. Snow is rare; if it comes, the village schools close for a day and children sled on the castle slope using fertiliser bags.

Getting stuck, getting out

Public transport is the weak link. A school bus leaves for Logroño at 07:45 and returns at 14:30; that’s it. Taxis from the airport must be pre-booked (Radio Taxi Logroño, +34 941 50 50 50) and cost €25-30 to the city. If you hire a car, the petrol station on the roundabout closes on Sunday – fill up on Saturday. The nearest train station is Calahorra, 12 km south; weekday buses connect at 13:10 and 18:00, but not at weekends. Miss the last service and a taxi back to the village is another €20.

A practical half-day (no clichés promised)

Land on the morning Ryanair from Stansted, pick up the Fiat 500 you booked because it was cheapest, drive six minutes to Agoncillo. Park behind the sports court – free, no ticket machines. Spend 45 minutes in the Würth Museum, another 20 circling the castle. Lunch at Chusmi: chuletón, clarete, espresso, €32 a head. Walk the river loop until the sun drops behind the poplars, then back to the airport for the 18:30 return. You will have seen one of Spain’s better small art collections, eaten beef that didn’t come from a supermarket, and walked beside a river older than any kingdom in Europe. That is enough. Anything more requires staying overnight, and Agoncillo, honest to the last, does not insist.