Full Article

about Grañón

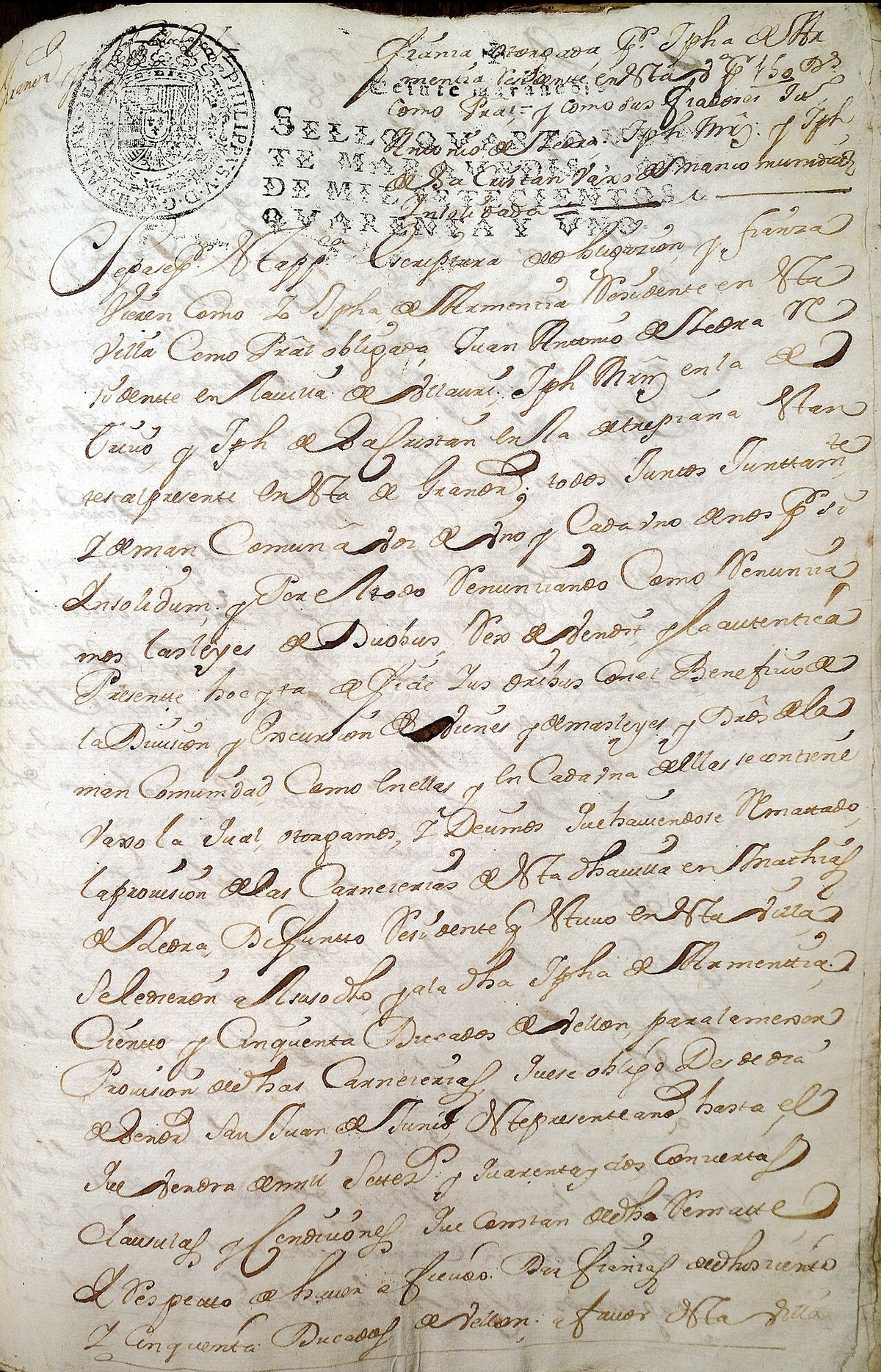

Last village on the Camino de Santiago in La Rioja; known for its pilgrim hospitality and altarpiece.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

Dawn Above the Riojan Plains

The church bells start at seven. Not the gentle Westminster chime Brits expect, but a full-throated bronze clang that rattles the attic beams of the albergue and shakes sleep from 40 pilgrims' bones. From the bell tower, the view stretches north across cereal fields that fade into the Cantabrian hills, 100 kilometres away. At 650 metres above sea level, Grañón catches the morning light earlier than anywhere for miles—one reason why this ridge has been inhabited since before the Romans hacked their road towards the silver mines.

Altitude matters here. Summers arrive late and leave early; winter wind whips across the meseta with nothing to stop it until the Pyrenees. Walkers setting out from Santo Domingo de la Calzada at sea level notice the temperature drop five degrees by the time they reach the village 12 kilometres later. Pack layers, even in May.

A Village That Measures Itself in Footsteps

You can walk from one end of Grañón to the other in four minutes. Count them: 200 metres along Calle Mayor, a left dog-leg past the stone bench where the old blokes sit, and you're already at the last house. The population—355 on the books, fewer in winter—fits inside the average London Waitrose car park. Yet the place feels bigger than its footprint suggests, mostly because half the people you meet are travelling through.

The Camino de Santiago splits the village like a spine. Yellow arrows appear on wheelie bins, door frames, even the bakery shutter. Locals have grown so used to foreigners that they greet strangers with a nod before deciding whether to switch from Riojan Spanish to the slow, clear version reserved for pilgrims. English is scarce; a handful of menus offer "lentejas" translated hopefully as "lentils stew."

The only real sight is the eighteenth-century Iglesia de San Juan Bautista, its stone tower visible from the LR-205 road long before the houses themselves. Inside, the altarpieces glow with the kind of gilt that makes Protestant visitors blink. More memorable is the attic dormitory overhead: mattresses lined up like a wartime field hospital, pilgrims' clothes strung on ropes between medieval beams. Ear-plugs are not optional—those bells are three metres above your head.

What the Guidebooks Don't Mention About Mountain Life

Grañón sits on the last proper ridge before the land tips onto the high plateau of Castile. That position creates micro-weather. Morning fog pools in the valley below, leaving the village marooned above a white sea. By 11 a.m. the sun has burned it off, but the wind arrives—steady, insistent, capable of turning an umbrella inside out before you've found the zip on your raincoat. In July this is welcome; in February it feels like someone left the fridge door open.

Rain behaves oddly at altitude. A black cloud can dump five minutes of stair-rod rain while you shelter in the bar, then blow east so fast the streets steam dry. Walkers used to British drizzle sometimes abandon waterproofs too soon and end up soaked a kilometre out of town. Keep the jacket handy until you reach the tree belt beyond the cemetery.

Winter brings another surprise: snow is rare but ice isn't. The stone alleys polish themselves into slides overnight. The council spreads grit from the back of a tractor at dawn; if you need to reach the loo block outside the albergue, crab-walk. Spring compensates with a burst of almond blossom that turns every orchard pink for ten days—usually the first week of April, though no one bets on it.

Eating When There's Only One Menu

Grocery choice comes down to a single ultramarinos the size of a village post office. Shelves hold tinned tuna, over-wrapped cheese and Rioja at €3.50 a bottle—cheaper than water in most airports. Fresh milk is intermittent; UHT rules. Stock up before Saturday afternoon because the shop shuts on Sunday and doesn't reopen until Tuesday if the owner visits her daughter in Logroño.

Evening meals revolve around Casa Galicia on the corner of the square. The pilgrims' menu costs €12 and arrives in four waves: soup thick enough to stand a spoon, plate of roast chicken and chips, yoghurt, then unlimited wine from a five-litre plastic container. Vegetarians get eggs—fried, scrambled or in a potato tortilla the diameter of a steering wheel. Arrive before seven; when the rice runs out, that's it. The next nearest restaurant is six kilometres down the hill in Castildelgado, and taxis are thin on the ground.

Breakfast is easier. The bakery opens at 6.30 a.m., lights blazing, smell of coffee drifting across the silent square. For €2 you get a buttered baguette and a café con leche strong enough to restart a heart. Stand at the bar with farmers in blue overalls and German hikers wearing identical merino tops; conversation is optional.

Walking Out Without Getting Lost

You don't need a ordnance-survey obsession to enjoy the surrounding paths—just remember that every track eventually meets either the N-120 or a threshing circle. A thirty-minute loop heads west from the church, drops past the cemetery, then follows a farm lane between wheat fields. Stone huts with thatched roofs—called chozos—dot the hillside, built by shepherds who needed overnight shelter when snow blocked the drove roads. Most are padlocked, but one near the Ermita de San Roque has had its door removed; peer inside and you'll see soot-blackened walls from a century of fires.

Serious hikers can pick up the GR-1 long-distance trail which coincides with the Camino for 8 kilometres towards Redecilla del Camino. The route climbs another 150 metres onto the Montes de Oca, a ridge notorious in medieval times for bandits and wolves. Wolves are gone; the bandits now run rogue taxi services charging €40 for the 20-minute ride back from Santo Domingo if you over-estimate your capacity for local Rioja.

How to Get Here (and Away Again)

Public transport stops at Santo Domingo de la Calzada. From Bilbao airport—two hours' flight from London—an ALSA coach runs twice daily to Santo Domingo (2 hrs 10 mins, €11). There is no bus up the hill to Grañón. Options are: taxi (€30 pre-booked via Santo Domingo Radio-Taxi), thumb (usually works in pilgrim season), or walk the old Roman road which the Camino follows. It's 12 kilometres with 350 metres of ascent; allow three hours if you're carrying more than a day-pack.

Leaving is simpler. Most walkers continue west towards Belorado, ticking off another 23 kilometres. If knees mutiny, the same taxi firm will collect from the bar terrace and deliver to Logroño train station in 45 minutes (€70). Trains to Madrid take two hours; connection to Barcelona is another three.

The Honest Verdict

Grañón won't keep you busy for a week. Come looking for gift shops or evening entertainment and you'll be asleep by nine. What the village offers is a rare intact snapshot of rural Spain—no boutique hotels, no souvenir tat, just stone houses that have weathered 500 winters and locals who still nod good-day because that's what you do. Stay one night, climb the bell tower at sunset, and you'll understand why pilgrims remember the place long after they've forgotten the cathedral cities. Just bring cash, ear-plugs, and a windproof jacket.