Full Article

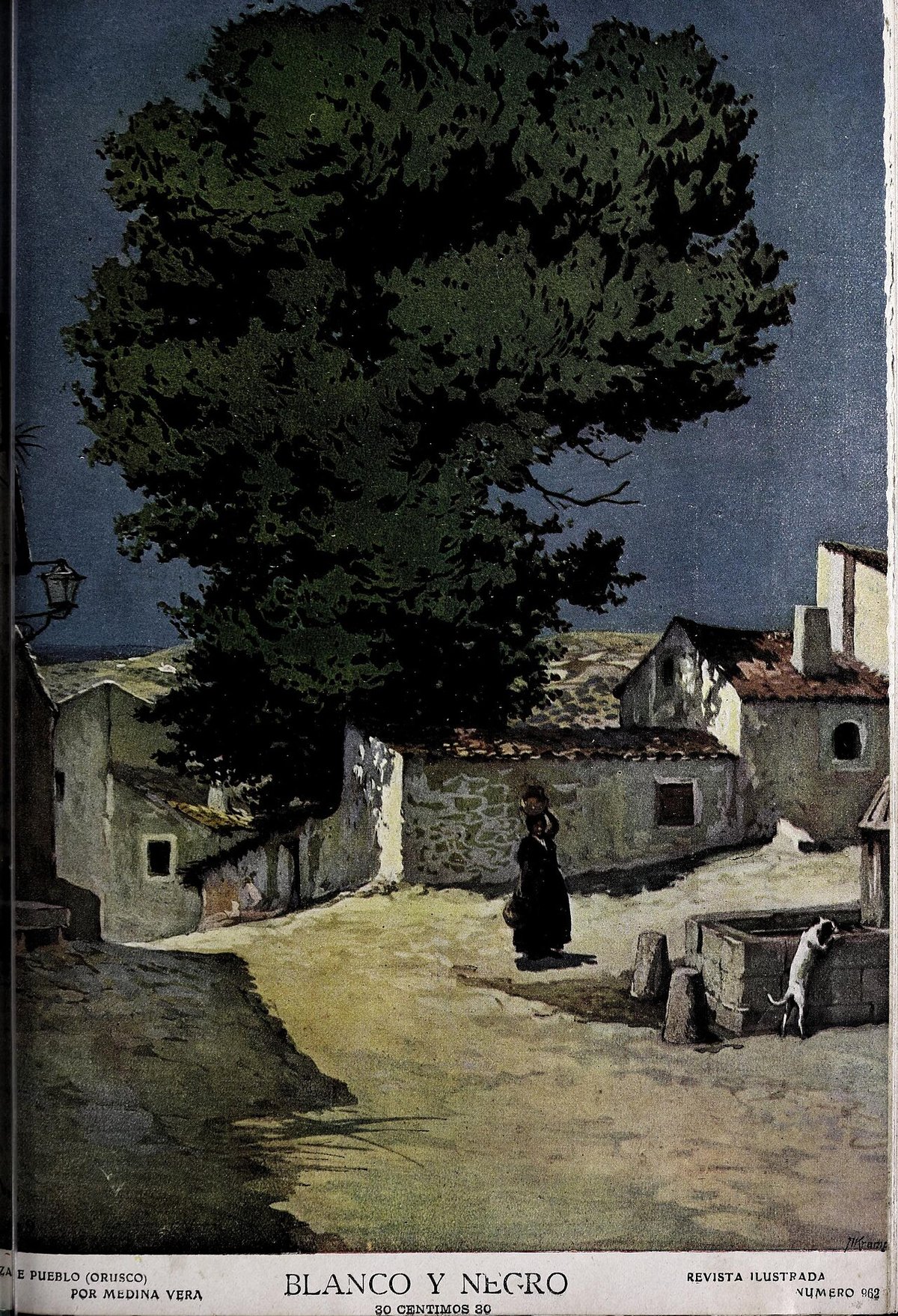

about Orusco de Tajuña

Tajuña river town with a paper-making tradition and plenty of springs.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The first thing you notice is the hush. Step off the bus at 646 m above the Tajuna valley and Madrid’s roar drops away, replaced by poplars rattling in the wind and the faint smell of wet earth from the irrigation channels. Orusco doesn’t shout for attention; it lets the altitude do the work. Even on a July afternoon the air arrives a couple of degrees cooler than at the capital’s Plaza Mayor, and by dusk you’ll be glad of a jumper.

A town that measures itself in wheat fields, not Metro stops

Orusco’s grid of low houses fits inside a single square kilometre, so the landmarks are measured by minutes, not miles. From the bus stop on Calle Real it’s a three-minute walk to the 16th-century tower of San Bartolomé, the parish church whose stone glows amber after five o’clock. Keep walking and you hit Plaza de la Constitución in another two; the iron balconies here still carry the green paint chosen by the last mayor, a farmer who reportedly picked the colour because it matched his tractor. The ayuntamiento occupies one side of the square, its clock running four minutes slow for as long as anyone can remember. No one resets it; the joke is that Orusco already has enough time on its hands.

Beyond the square the streets taper into alleys barely wide enough for a Seat Ibiza. Peek over any wall and you’ll see back gardens given over to vegetable plots rather than patios. This is still a working cereal village: wheat, barley and the occasional stripe of olive trees. At harvest in late June the combine harvesters trundle in at dawn and the only queue in town forms outside the cooperative’s grain store, not the bakery.

The river that turns farmland into a beer advert

Five minutes downhill, the Tajuna river rewrites the script. Poplars replace wheat, herons replace sparrows, and the water smells of mint crushed under bicycle tyres. A 3-km loop follows the east bank, flat enough for pushchairs but rough enough to demand proper shoes. Mid-week you might share it with one dog-walker and a retired fisherman who swears the barbel are bigger since the sewage plant upstream closed. Summer Saturdays are busier: families from Madrid park at the old railway station and march the shaded stretch before lunch, but by 3 p.m. they’ve vanished back to air-conditioning and the river belongs to dragonflies again.

Serious walkers can stitch together farm tracks south towards Carabaña. The path climbs gently through olive groves to a low ridge where the valley unfurls like a green tablecloth; from here you can trace the river’s silver thread all the way to the granite bulk of the Gredos on a clear day. Allow two hours out and back, carry water—there’s no fountain after the first kilometre—and start early; by 11 a.m. the sun has the authority of a headmaster.

How to arrive without your own wheels

Public transport exists, but it obeys agricultural time, not tourist time. Interurban bus 326 leaves Madrid’s Conde de Casal station roughly every 90 minutes on weekdays, less at weekends. The journey takes 55 minutes and costs €4.20 each way; buy the ticket on board and have small change. Sunday’s last return departure can be as early as 18:30, so check crtm.es the night before. Miss it and a taxi to the next village with a later service—Arganda del Rey—will lighten your wallet by €35.

Drivers follow the A-3 to exit 26, then the M-313 through olive terraces that look like Andalucía gone modest. Petrol is cheaper in Arganda, so fill up before the final 12 km. In town, park on Calle del Carmen; it’s free, unsigned and usually half-empty.

What to eat when the church bell strikes one

Orusco’s restaurants number exactly two. El Cazador on Calle Real does roast lamb (cordero asado) in half portions—enough for one hungry cyclist—and will split a plate if you ask nicely. House red comes from Valdepeñas and costs €2.50 a glass, served in the chunky tumblers Spanish grandmothers reserve for breakfast coffee. Across the square, Bar El Pilar opens at 07:00 for farmers and serves a proper tortilla: thick, slightly runny, with caramelised onion. Order a cortado (espresso cut with a dash of milk) and you’ll get a free biscuit the size of a 50-pence piece; dunking is expected.

For picnic supplies the bakery on Pablo Iglesias sells empanadillas the size of a pasty—tuna or chorizo, €1.40 each—designed for field workers and perfect for the river path. There is no cash machine in the village; the nearest is back up the hill at the petrol station on the M-313, so bring notes.

The disused railway that pedals better than it ever ran

The Vía Verde del Tajuña is the reason most outsiders know the village exists. The line closed in 1987 after a century of moving grain, not people; today its 22 km of compacted gravel make one of Madrid region’s quietest cycle paths. The gradient rarely tops 2 %, so you can cover the full stretch to Arganda and back in a leisurely three hours, bridges included. Bring your own bike—there is no hire shop—or reserve one in Chinchón before you arrive. Mobile signal vanishes inside the two tunnels west of Orusco, so download offline maps and remember that the only bar en route is at the ruined station of Carabaña, 6 km away. It opens sporadically; pack a second bottle of water as insurance.

Winter transforms the greenway into a wind tunnel; locals stick to the river path and leave the railway to hard-core MAMILs in gilets. After heavy rain the tunnels flood to axle depth—check @ViaVerdeTajuna on Twitter for closure notices.

When to come, and when to stay away

April and May stitch poppies into the wheat and the temperature hovers round 20 °C—ideal for walking before the sun turns serious. September evenings smell of crushed grapes from the neighbouring Vegas’s small plots; the light is soft enough for photography without filters. August midday is brutal: 35 °C in the shade, almost no breeze, and bars shut between 16:00 and 20:00 while staff sleep. If you must come in high summer, catch the 08:00 bus from Madrid, walk the river, eat lunch, and be on the 15:00 return. The village offers exactly one small playa fluvial—really just a widened bend with a concrete slip—and it fills up with fizzy-drink cans by noon.

Fiestas are short, loud and local. San Bartolomé on 24 August closes the main street for a weekend of brass bands and procession; parking becomes theoretical and the bakery runs out of empanadillas by 10 a.m. Semana Santa processions are quieter—one paso, one trumpet, and every resident over fifty dressed in black. Tourists are welcome but not announced; if you want a seat at Mass, arrive 20 minutes early.

The bottom line

Orusco won’t keep you busy for a week. It might not even fill a day unless you walk the full greenway or combine it with lunch in Chinchón. What it does offer is a corrective to Madrid’s 24-hour tempo: a place where the loudest sound at 2 p.m. is a bicycle freewheeling downhill and where the evening news is still read aloud in the bar. Come for the river shade, the stone tower that’s been leaning since the 1800s, and the realisation that the meseta isn’t all wind turbines and wheat; sometimes it’s just a quiet bench under a poplar, a cortado in a thick glass, and a bus timetable that forces you to slow down.