Full Article

about Getafe

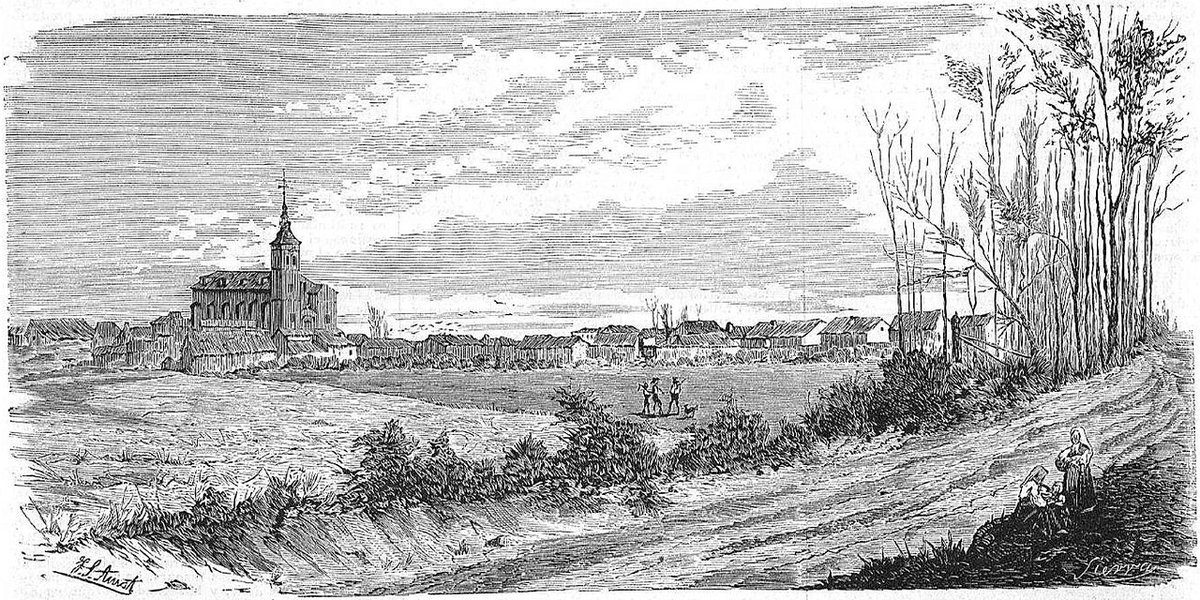

Industrial and university city; home to Cerro de los Ángeles, considered the geographic center of the peninsula.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

Six hundred and twenty-three metres above sea-level, the wind across the Meseta hits Getafe five degrees cooler than it does down in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol. Stand on the Cerro de los Ángeles, the modest rise that claims to be the geographical centre of the Iberian Peninsula, and the capital’s skyscrapers shimmer on the northern horizon like a promise you’re not sure you want to keep. Turn south and the view is of container parks, hangars and the runway of the old air-force base: this is commuter-land, not postcard-land, and the city is relaxed about the fact.

Most visitors arrive by accident—an affordable rental flat that turned out to be thirty minutes from Atocha, or a Ryanair flight diverted to the nearby Cuatro Vientos airfield. Guidebooks give Getafe two lines, usually ending with “little of interest”. That verdict is half right: the old quarter fits into four short streets and the starring monument, the Iglesia de Santa María Magdalena, locks its doors between services. Yet if you are already staying in Madrid and fancy seeing how most madrileños actually live—rather than how they appear in curated Instagram reels—the Cercanías train (line C-4, €2.60 with the Abono Transporte) drops you here in eighteen minutes. Stay for lunch, not for the weekend, and the place makes sense.

What passes for a centre

Constitution Square is a rectangle of granite paving flanked by cafés whose terraces colonise every sunlit angle before 11 a.m. Office workers from the university campus dash in for a cortado and a cigarillo; retired men read Marca on the benches and ignore the pigeons. The neoclassical town hall is pretty enough to photograph once, then you’ve exhausted its possibilities. Behind it, the Magdalena tower rises in warm brick, a 13th-century exclamation mark of Mudéjar brickwork. Push the heavy door at Mass time and you’ll find a dim interior scented with candle wax and floor polish, the carved ceiling lost in gloom. Come outside again and the contrast is immediate: a Deliveroo rider leans his bike against the apse, helmet balanced on the Gothic buttress while he checks orders.

Five minutes east, the former Hospital de San José survives as a municipal office block. You can walk the cloister in three minutes; the baroque church now hosts civil weddings on Saturday mornings, confetti drifting across the 17th-century stonework. It is history repurposed rather than embalmed, and that, too, is typical of Getafe—continuity by pragmatism.

Aeronautical detour (if the guard is in a good mood)

The Museo de Aeronáutica y Astronáutica sits inside the military perimeter on the old Carretera de Andalucía. Entry is free but you must e-mail your passport details at least a week ahead; turn up on spec and a polite sentry will wave you back towards the bus stop. Inside, a 1950s Junkers and various fighter trainers doze under a cavernous hangar. Enthusiasts will forgive the bilingual labels that stop mid-sentence; casual visitors may decide the trip is disproportionate to the payoff. Either way, factor in a 25-minute walk from the station and check the return timetable—buses shrink to one an hour after 15:00.

Lunch without tourists

Spanish colleagues insist the city’s best cocido is served at Casa José on Calle Jara, but the dining room feels like a 1970s working-men’s club and the menu is Spanish-only. A safer introduction is Casa Gallega on Calle Toledo, where grilled squid arrive the size of a toddler’s fist, properly charred and under €12. If confidence is low, the food court above the Mercado de Getafe does roast chicken, chips and a can of pop for €7—perfect for children who regard garlic as a human-rights violation. Wash it down with a caña of Mahou; the brewery is just down the road and the lager tastes noticeably fresher here than it does after the metro ride back to Sol.

Sunday is a gastronomic write-off—metal shutters everywhere, even the Chinese bazaars taking a breather. Plan accordingly.

A hill, a view, a chapel no one asked for

The Cerro de los Ángeles is less a hill than a gentle swelling you could cycle up in third gear. A 14-metre statue of the Sacred Heart crowns the summit, copied from the more famous version in Lisbon. Pilgrims arrive twice a year; the rest of the time the plateau belongs to kite-flying teenagers and British geography teachers ticking off “the centre of Spain”. On a clear winter afternoon the granite basin around Madrid glitters, commuter trains threading across it like toys. Bring a jacket—600 metres feels alpine once the sun drops—and don’t expect a café. The nearest vending machine is a ten-minute walk back towards the industrial estate.

Evenings: students, not flamenco

Nightlife clusters south of the railway, around Avenida de la Universidad. Bars offer €1.50 bottles of beer, table football and soundtracks that jump from reggaeton to 90s Britpop without apology. The crowd is overwhelmingly Spanish undergraduates; tourists are such a novelty that barmen will practise their English on you and refuse payment for the second round. Last orders coincide with the 23:27 train to Atocha—miss it and the night bus (N801) lumbers in every 90 minutes, or you can queue for a taxi (€38 flat fare, card machine usually “broken”). British stag blogs warn this is where budgets go to die; they’re not wrong.

The honest calendar

Spring and autumn give you pavement life without the furnace. In May the university lawns turn into improvised cricket pitches—Indian and Pakistani PhD students versus Spanish faculty—and the temperature hovers in the low 20s. July belongs to the Fiestas de la Magdalena: fairground rides block the main road, fireworks rattle the windows, and hotel prices (should you insist on staying) double. Winter is crisp, often sunny, but the wind scything across the plateau can make the ten-minute walk from church to bar feel like expedition training.

How long is too long?

Allocate a morning for the old quarter plus lunch, add another hour if you secure museum clearance. Treat the place as Madrid’s sixth district rather than a destination in its own right and you leave content rather than cheated. Guidebook indifference exists for a reason: Getafe’s charm is incidental, accidental and mostly concrete. Yet for travellers who measure value in eye-contact with barmen, correctly priced coffee and the low rumble of a place that refuses to perform its past, that may be enough.