Full Article

about Guadarrama

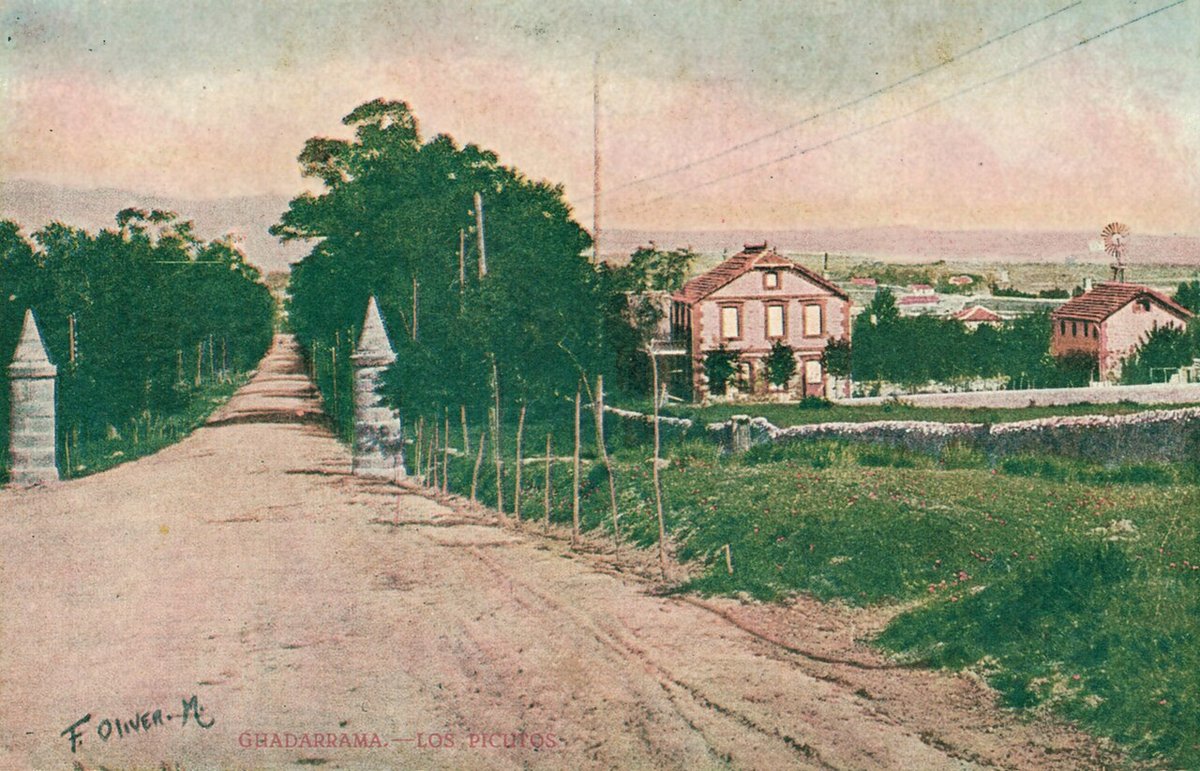

Tourist and summer town; starting point for climbing the Puerto de los Leones and exploring the sierra.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The church bell strikes noon just as the morning chill lifts off the granite walls. At 981 metres above sea level, Guadarrama's San Miguel Arcángel stands a full degree cooler than Madrid's Puerta del Sol, a difference you'll feel in your bones before you see it on a thermometer. This is where the Spanish capital's granite gives way to pine, where office workers trade suit jackets for walking poles, and where the Sierra de Guadarrama National Park begins not with a visitor centre but with a village bakery that still weighs bread by the kilo.

Between City and Summit

Guadarrama's main street, Calle Real, runs exactly 54 kilometres west of Madrid's Royal Palace. The journey takes 45 minutes on a clear Tuesday morning, closer to ninety when half of Madrid heads for the hills on Saturday. The A-6 motorway climbs steadily after Las Rozas; drivers who've been admiring their fuel consumption suddenly watch the gauge drop as the engine works against the gradient.

The village itself spills down a south-facing slope, a practical arrangement that maximises winter sunshine. Stone houses with terracotta roofs line narrow lanes built centuries before the Seat Ibiza became Spain's best-selling car. Parking requires patience and a tolerance for tight manoeuvres; locals have perfected the art of reversing into spaces that appear two feet shorter than their vehicles. Visitors arriving by train take the C-8b cercanías to Cercedilla, then either taxi the remaining eight kilometres or wait for the twice-daily bus that operates on a timetable best described as optimistic.

What strikes British visitors first is the air density. After Madrid's thin plateau atmosphere, breathing here feels like someone turned up the oxygen. The second revelation comes at sundown when temperatures plummet. Even in July, when the capital swelters at 38°C, Guadarrama's evening breeze demands a jumper. Pack layers, always. The British habit of checking weather apps becomes essential; mountain weather here changes faster than a London commute.

Stone, Pine and the Smell of Rain on Granite

The parish church of San Miguel Arcángel dominates the skyline without dominating the village. Built in the sixteenth century from local granite, its tower serves as both spiritual beacon and practical landmark for walkers returning from the hills. Inside, the architecture speaks of function over grandeur: thick walls designed to survive winter storms, a nave proportioned to accommodate the population of a village that then numbered hundreds, not thousands.

Behind the church, lanes narrow to medieval width. Granite lintels bear the marks of masons who worked without power tools; wooden balconies sag under the weight of geraniums that thrive in the mountain air. These houses represent Guadarrama's original fabric, though the twentieth century brought expansion that even the most creative estate agent couldn't describe as sympathetic. Modern apartment blocks occupy the eastern approach, their design philosophy apparently borrowed from a 1970s Birmingham shopping centre. The contrast proves jarring, but it also keeps property prices reasonable for a village within an hour of a European capital.

The true architecture lies beyond the urban edge. Within five minutes' walk, concrete gives way to dehesa oakland and pine plantation. Paths signed by the regional government branch into the national park, their waymarks painted in yellow and white. The nearest proper walk, a circuit to the Puerto de Navacerrada, begins at the football pitch and climbs steadily through Scots pine. The going underfoot varies from packed earth to sections where tree roots create natural steps. After forty minutes, the track emerges onto a ridge offering views north toward Segovia's plains. On clear days, the cathedral spires of that city appear as miniature ivory needles against brown meseta.

What the Mountain Gives

Guadarrama's restaurants know their market. Weekend tables fill with Madrileños seeking cocido madrileño, the chickpea-based stew that tastes better at altitude. Portions challenge even the hungriest walker; the standard serving feeds two adequately, three if you've loaded up on bread. Chuletón, a rib-eye steak cut thick enough to require its own postcode, arrives sizzling on a heated plate. Vegetarians face limited options, though patatas revolconas – paprika-spiced mash topped with crispy pork belly – can be ordered without the meat for those prepared to negotiate in Spanish.

Local honey appears on every breakfast table, its flavour reflecting the wildflowers that bloom according to altitude rather than calendar. April brings crocuses at 1,200 metres; the same flowers emerge in Guadarrama's lower meadows during March. The village market operates Saturday mornings in the Plaza Mayor, where a British pound still converts favourably enough to make local cheese purchases feel almost free. Queso de oveja, made from sheep that graze the surrounding hills, carries a subtle nuttiness absent from supermarket versions.

Water matters here. The village sits above an aquifer that once supplied Madrid before engineering projects tapped the Lozoya River. Public fountains still run potable water; filling stations beside the church offer unlimited refills for walkers. Carry bottles. Mountain cafés exist, but they're scattered and seasonal. The nearest proper refreshment stop to the village lies three kilometres out at La Jarosa reservoir, where a seasonal bar serves coffee strong enough to restart a stalled heart.

Seasons of Stone and Sky

Spring arrives late and dramatic. Snow can fall as late as April; the same week might see temperatures reach 20°C by afternoon. This unpredictability creates extraordinary walking conditions. The Senda de las Carboneras, a six-kilometre loop through abandoned charcoal burners' clearings, bursts with wildflowers during May. British visitors accustomed to Dartmoor's muted palette find slopes painted with lupins, poppies and wild marjoram that scents the air after rain.

Summer brings Madrid's heat refugees. Sundays see the village swell as families escape the capital's concrete ovens. Picnic areas below the Puerto de Navacerrada fill by 11 am; walkers seeking solitude should start early or choose weekday visits. The upside comes in evening when temperatures drop to comfortable sleeping levels. Most accommodation lacks air conditioning; it simply isn't necessary when nights average 15°C even in August.

Autumn might be Guadarrama's finest season. October's colours transform the oak and beech woods above the village into a palette that would shame a Cotswold postcard. The crowds thin, prices drop, and walking conditions reach perfection: cool mornings, warm afternoons, clear air that makes the 120-kilometre view to Madrid's skyscrapers appear close enough to touch. This is mushroom season; locals guard their foraging spots with the same secrecy British anglers protect fishing beats.

Winter divides opinion. Snow arrives reliably from December through March, though climate change has made predictions hazardous. The village itself rarely sees deep accumulation; the same storm that drops two centimetres here might deliver half a metre five hundred metres higher. What winter guarantees is solitude. Hotels offer rates that seem misprinted; restaurants serve warming dishes that justify the calories burned during mountain walks. The catch comes with access. Sudden snow can close the A-6; trains continue running but require checking updated timetables online.

Guadarrama works best as a base rather than a destination. The village offers enough for an afternoon's wandering, but its real value lies in proximity. Within thirty minutes' drive lie medieval Segovia, El Escorial's monastery, and walking routes ranging from gentle valley strolls to serious ascents above 2,000 metres. Stay three nights minimum; four allows for weather contingencies without feeling rushed. Book midweek if possible; weekends bring Spanish city dwellers whose idea of mountain quiet differs from British expectations.

The mountain air clears more than lungs. Standing above Guadarrama at dusk, watching streetlights flicker on while the Sierra's western ridges glow orange, you understand why Madrid's residents have escaped here for centuries. This isn't wilderness; it's civilisation's edge, where coffee arrives within walking distance of ibex tracks, and where tomorrow's weather matters more than yesterday's news. Bring good boots, pack that extra jumper, and remember that Spanish mountain logic operates on its own schedule. The church bell will ring regardless; whether you answer its call or head for higher ground remains entirely your choice.