Full Article

about Navacerrada

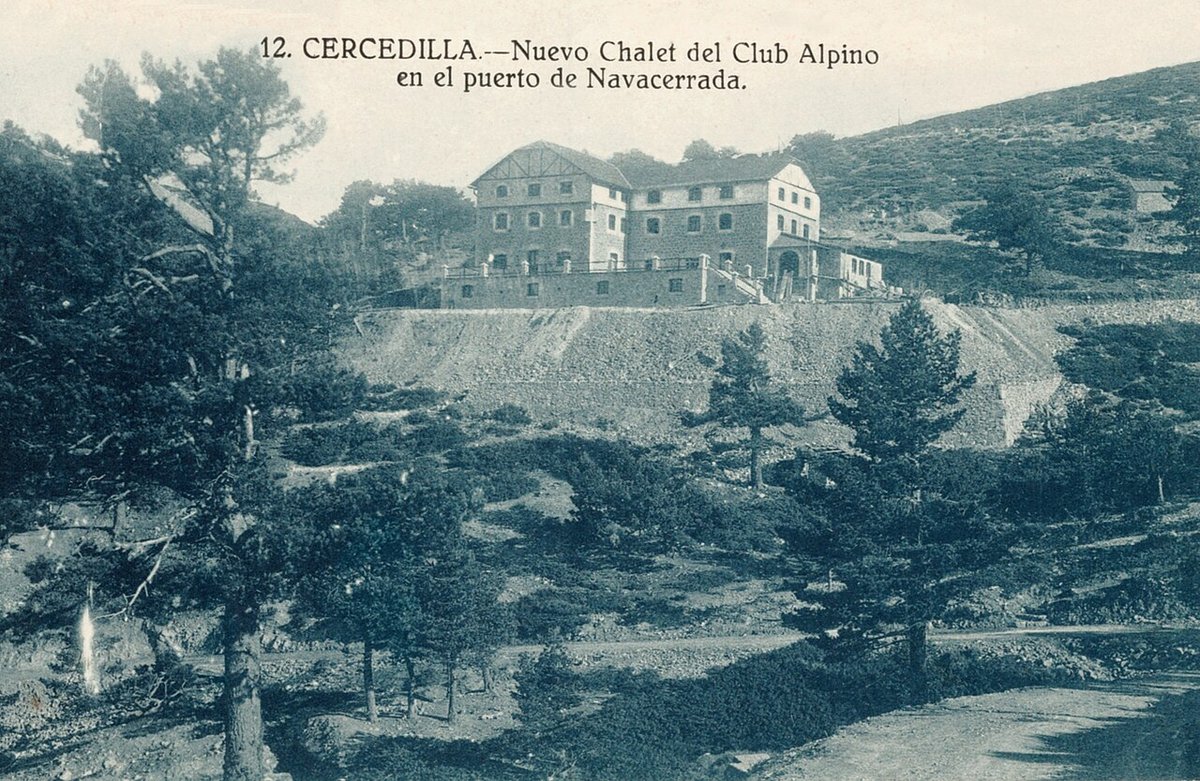

Mountain village and ski resort; alpine architecture, lively tourist scene.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The train from Madrid's Chamartín station drops you at Cercedilla, 52 kilometres north-west of the capital. From there, a narrow-gauge line nicknamed the "Tren de Cotos" climbs another 600 metres in twenty minutes, corkscrewing through pine forest until the carriage windows fog with altitude. When the doors hiss open at Puerto de Navacerrada station, the air is ten degrees cooler than back in the city—and the smell is resin, not diesel.

Most passengers stride straight towards the ski lifts that crown the 1,858-metre pass, but the smarter move is to turn downhill. A twenty-minute footpath (signed “Navacerrada pueblo, 2.1 km”) threads between broom and juniper, then deposits you in a granite-built village that has spent centuries intercepting traffic between Castile’s two plateaux. At 1,203 metres, Navacerrada is high enough to escape Madrid’s furnace in July, yet low enough that its 3,282 inhabitants don’t spend half the year snowed in.

Stone, Timber and the Smell of Roast Lamb

The village centre folds around the sixteenth-century church of La Natividad. There is no ornamental plaza: houses simply step up the slope until the road becomes a footpath. Rooflines are slate, walls are the same grey granite hacked from nearby quarries, and balconies are just wide enough for a geranium pot. Walk Calle Real at 11 a.m. on a weekday and the dominant noise is a butcher’s bandsaw; by noon it is the scrape of chairs on tile as waiters set zinc-topped tables for the menú del día.

That menu rarely changes: cocido madrileño on Tuesdays, cordero asado at weekends, judiones de El Barco—buttery white beans from the neighbouring province of Ávila—whenever the cook feels like showing off. Portions are calibrated for quarry workers, not spa guests; ask for a half-ración if you want to stay awake for the afternoon hike. Asador Espinosa, opposite the church, still cooks its lamb over holm-oak embers in the same brick hearth installed in 1954. Expect to pay €22 for a quarter kilo, plus another €3 for the wine jug that arrives whether you order it or not.

Snow Business, Summer Breathers

Navacerrada’s relationship with winter is transactional. When the Guadarrama fetch enough snow, the pass becomes Madrid’s nearest ski slope: four chair-lifts, sixteen runs, rental shops that will glue a season’s worth of wax to your city shoes if you let them. Locals roll their eyes at the hype—some seasons the lifts open barely sixty days. Check webcams before you set off; a brown hillside means the resort is selling lift passes for artificial ribbons that feel like frozen porridge.

Come off-season, the same infrastructure becomes a vantage point. The upper chair-lift will carry hikers uphill for €6 single, saving 400 metres of ascent. From the top station it is a gentle ridge walk to Siete Picos, whose seven humps give a saw-tooth silhouette visible from Madrid on clear days. Allow three hours round trip; bring a jacket even in August—Guadarrama weather can swing from 28 °C in the village to sleet on the ridge within the time it takes to eat a bocadillo.

Water, Birds and the Ghost of a Dictator

Below the pass, the Laguna de los Pájaros is little more than a glacial puddle, but its 2-kilometre loop is the village’s most popular pre-lunch stroll. Interpretation boards explain how the wetlands filter Madrid’s drinking water; herons and marsh harriers use the reeds as a motorway services between the plateau and the plain. Extend the walk another hour and you reach the ruins of Valdemanco fortress, a fifteenth-century stronghold later converted into a summer retreat for General Franco. The stone fireplace is still intact; locals claim the chimney draws well, though no one volunteers to test it.

Sunday Chaos, Wednesday Calm

Weekends are a different village. By 10 a.m. Saturday the M-601 is nose-to-tail with Madrid cars carrying skis on roof racks and mountain bikes on hatchbacks. Parking near the church costs €2 an hour; spaces on the pass itself are free but full by 8:30. Queues at the bakery stretch twenty deep for chocolate-filled napolitanas; the Sunday antiques market on Avenida de Madrid clogs the only flat street with typewriters, brass mortars and, for some reason, a disproportionate number of ZX Spectrum computers.

Arrive Tuesday through Thursday and you get the counter-version. Waitresses have time to explain that “Navacerrada” refers not to a naval battle but to the historic mountain gate (cerrada = enclosed pass) that shepherds used when driving flocks between summer and winter pastures. Hotel prices drop by a third; the terrace of La Fonda Real catches sun from 11 a.m. till dusk, perfect for a caña and a book without anyone asking whether you’ve “done” Peñalara yet.

Getting Up, Getting Down

Public transport is workable but demands patience. From Madrid’s Moncloa interchange, bus 691 reaches the village in 55 minutes for €4.20; the last return leaves at 21:15, so don’t linger over post-hike coffees. The rail-plus-cogwheel route via Cercedilla is more scenic but slower: allow 90 minutes door-to-door. In winter, add another thirty minutes for the mandatory tyre-chain parade when snow falls on the pass.

Drivers should carry chains October–April; the Guardia Civil turn traffic back at the first flake. On blue-sky winter Sundays, leave before 4 p.m. or join the 15-kilometre tailback that snakes towards the capital at walking pace.

What to Pack, What to Skip

Even a July visit can end in a hailstorm above 1,800 metres. Layering beats a single thick coat; gloves live in pockets year-round. Trainers suffice for village lanes, but the granite dust on Peñalara’s paths eats fabric: approach shoes or light boots pay for themselves.

Skip the souvenir shops selling resin chamois and flamenco fridge magnets—this is Castile, not Andalucía. Buy instead a 250-gram block of local pine honey from the cooperative on Calle de la Estación; it costs €6 and smells exactly like the forest you just walked through.

Leaving the Door Ajar

Navacerrada never pretends to be undiscovered; it is, after all, the mountain gate that Madrid keeps propped open. The trick is to pass through at the right hour, on the right day, with the right expectations. Come mid-week, order the judiones, walk until the city’s roar is replaced by wind in the pines, and catch the evening train while the peaks behind you flush pink. You will share the carriage with teachers, nurses and civil servants who do the same escape every month. None of them would call it a hidden gem—they simply call it breathing.