Full Article

about Lorca

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The lift to Lorca’s castle clanks shut at 14:00 sharp. If the Levante wind is whipping across the valley they simply switch it off, leaving visitors with two choices: turn back, or climb the stone serpent of a path that medieval sentries once legged in full armour. Most Brits arrive expecting a gentle stroll round another sun-bleached ruin; instead they get calf muscles and a view that stretches to the Sierra de Alcaraz 70 km away. At 353 m above the Guadalentín valley, Lorca is the highest of Murcia’s sizeable towns, and the air up here is a dry, fragrant blast of rosemary and hot stone.

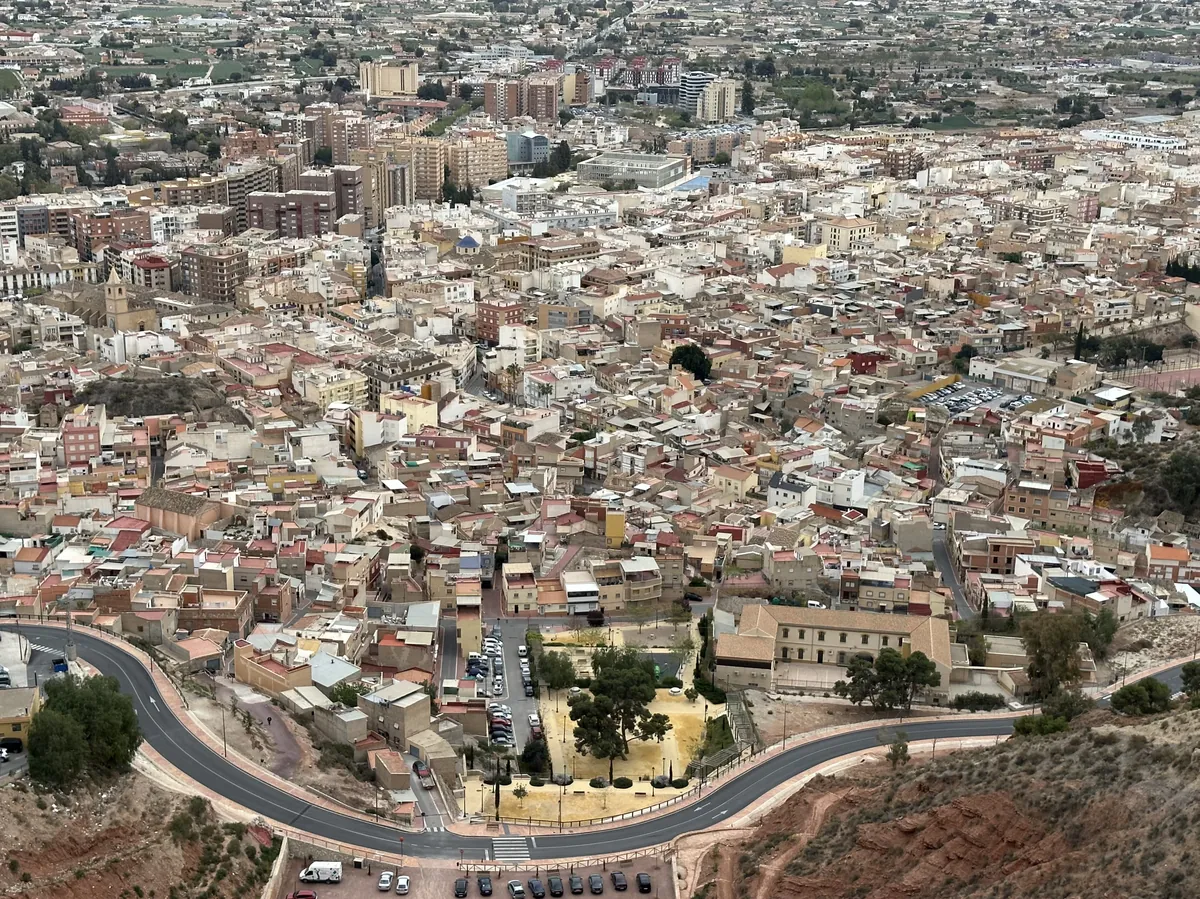

From the battlements you can read the town’s entire biography. South-east lies the almond-coloured sprawl of modern suburbs; directly below, the compact medieval core, still ringed by fragments of Islamic wall; due south, the dry riverbed that acted as frontier between Castile and the Nasrid kingdom of Granada for two centuries. The fortress itself – the Fortaleza del Sol – now doubles as a Parador, so you can sleep in a 13th-century tower for about €130 a night if you fancy waking up to that panorama. Day visitors pay €8 for the “tourist bracelet” which covers the castle, several churches and the embroidery museums; buy it at the ticket hut because nobody reminds you later.

Inside the stone labyrinth

Drop down from the castle and the temperature rises five degrees. Lorca’s historic centre is built from a local limestone that glows butter-yellow at sunrise and turns parchment-pale by midday, giving the streets a uniform coat of warm paint. The effect is oddly English-village until you notice the baroque balconies and the ironwork grilled to shut out the sun, not the rain. Plaza de España acts as the natural meeting point: café tables under canvas, the 16th-century Collegiate of San Patricio rising at one end, locals arguing over football at 120 dB. Thursday is market day – granted by royal charter in 1465 and still doing a roaring trade in peppers, pants and screwdrivers. Stallholders fold away by 14:00; arrive late and all you’ll see is plastic crates being stacked.

Walk two minutes south and you hit Calle Santo Domingo, better known as the “Calle de los Palacios” because every doorway belongs to a 17th-century silk merchant trying to outdo his neighbour. The Guevara Palace, nicknamed Casa de las Columnas, is the show-off of the bunch: a wedding-cake façade smothered in carved laurel wreaths and topped by a lion wearing the family crest. Inside, the courtyard is cool enough to make you forget the mercury outside; guided tours run on the hour in English for €4, but groups are capped at fifteen so you’re not shuffling like Heathrow security.

When the city stitches all night

Lorca’s reputation beyond Murcia rests on one week of the year. Semana Santa here is less solemn parade, more embroidered arms race. Two rival brotherhoods – the Blues and the Whites – spend twelve months and upwards of €30,000 sewing gold thread onto velvet cloaks that will be worn once, for three hours, at 3 a.m., on the back of a horse groomed to mirror-image perfection. The result feels like stumbling onto a film set where the costume budget dwarfs the script: biblical floats the size of removal lorries, drummers in knee-length silk socks, and riders carrying 18th-century sabres they genuinely know how to use. If you want to witness the spectacle, book accommodation before Christmas; if you just want to see the textiles in daylight, the Museo de Bordmanto opens year-round and is half-empty on a Tuesday.

Outside Easter the city relaxes. Museums keep Spanish hours – morning slot 10-14:00, evening 17-19:00 – and are shut on Monday, a fact forgotten by every second tourist who turns up with a print-out of TripAdvisor’s “Top Five Things”. The Archaeological Museum gives context: pottery from the Iberian settlement that predated the Romans, a mosaic floor lifted from a villa destroyed in the 2011 earthquake, and a short film explaining why Lorca wobbles – it sits on the same fault line as nearby Alhama de Murcia. The quake caused €1.2 billion of damage; scaffolding still clings to a couple of church towers, but most historic buildings have been patched so expertly you’d never guess.

Food that doesn’t involve chips

Lorca is 35 km from the sea, so forget paella postcards. Instead you get the cooking of inland Murcia: rice with rabbit (tastes like chicken, costs €12), caldo murciano – a tomato and garlic soup thickened with egg – and migas, fried breadcrumbs tossed with chorizo nuggets. Vegetarians can survive by requesting dishes “sin jamón”; most waiters will suggest the pisto murciano, a peppy ratatouille topped by a slab of grilled goat’s cheese. Sweet teeth should queue at Cafetería Castillo on Plaza de España for churros that emerge from the fryer at 8 a.m. and sell out by 10. Wash them down with café con leche served in glasses the size of teacups – the local measure of hospitality.

Wine drinkers head for the Monastrell route. The grape loves the arid climate and produces inky reds that punch above their price. Bodegas such as Bodegas Juan Gil open at weekends for €8 tastings; English is spoken if you ring ahead. Driving is essential: public transport peters out at the town boundary and taxis are thin on the ground.

Heat, hills and how to get here

Summer is honest-to-goodness hot – 35 °C is routine in July – but the altitude sucks some of the sting out of the nights. Spring and autumn sit in the mid-20s and empty the streets of anyone who isn’t local. Winter days hover around 15 °C, enough for a fleece at noon, though the castle car park can be a wind tunnel that feels closer to Yorkshire in March.

The nearest airport is Murcia-Corvera, 75 minutes by hire car down the A-7, Spain’s answer to the M25 but with toll-free tarmac. Almería is slightly farther and usually pricier to fly into. Trains run from Murcia city twice daily, but the station is 4 km below the old town; without wheels you’ll spend €15 on taxis before you’ve seen a baroque balcony.

Leave time for the hills. Signed footpaths strike north into the Sierra del Puerto, following old silk-trade tracks past almond terraces and abandoned watermills. The four-kilometre loop from the castle to the Moorish watchtower of Torrecilla takes ninety minutes, requires trainers not walking boots, and delivers the same sandstone vistas the fortress guards saw 800 years ago.

Lorca won’t keep you for long – a day and a night covers the monuments, the museums and a respectable dinner – but it lingers longer than the guidebooks suggest. Perhaps it’s the sight of a city that still embroiders for twelve months just to look magnificent for one night, or the realisation that Spanish history isn’t locked in a display case; it’s being swept off the streets each evening with buckets of water and a stiff broom, ready for tomorrow’s procession of sun, dust and neighbourly noise.