Full Article

about Tiebas-Muruarte de Reta

Known for the ruins of Castillo de Tiebas, a former royal residence, and its historic quarry.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

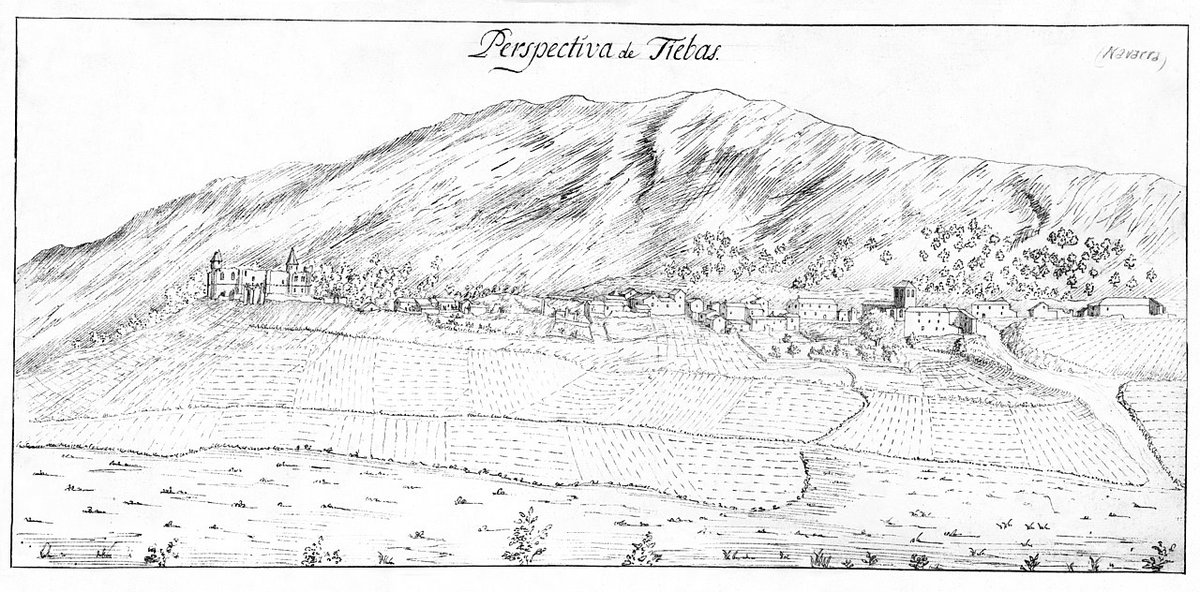

Tiebas-Muruarte de Reta appears on the horizon as a broken tooth. The castle keep still stands, but daylight shows the gaps: entire walls sheared off, staircases that end in mid-air, swallows nesting where kings once dined. From the N-121 the silhouette tricks motorists into thinking they’ve found a full-blown medieval complex; close-up it is a controlled ruin, fenced off in places, informative in a blunt, ruinous way. The village below—really two hamlets fused by council decree—counts barely five hundred souls, enough to keep one bar profitable and two churches unlocked on feast days.

Wheat, wind and a king’s divorce

Navarre’s southern plain is cereal country. From April the fields fluorescence green, then bleach to gold so bright it hurts the eyes. Tiebas sits on a low lava plug, just high enough to command the surrounding quilt of smallholdings. That slight elevation persuaded Charles III of Navarre to build a palace-fortress here in 1395; he needed somewhere to imprison his estranged wife, doña Leonor, while lawyers argued over the annulment. The marriage failed, the castle survived two civil wars and an earthquake, then gradually slid into the landscape. What remains is a free-to-enter archaeological park with bilingual panels whose English veers between helpful and comic (“Beware the precipitations”). Download the PDF guide before you leave Pamplona; phone ahead (+34 848 42 00 42) to check the tower isn’t closed for stabilisation work—scaffolding appears without warning.

The walk from the square to the summit takes eight minutes on a cobbled lane wide enough for a single donkey. Oats grow between the stones. At the top the 360-degree view explains the strategic logic: the Pyrenees hover white on the northern horizon, while the Camino de Santiago threads east–west across the plain below. Pilgrims appear as moving dots; the wind carries snatches of French and Korean. A stone bench faces the best angle for photographs, though the Instagram crowd usually give up when they realise the castle will never look intact again. That honesty is oddly refreshing.

Two villages, one till receipt

Muruarte de Reta, the second half of the municipality, lies two kilometres uphill past sunflower plots and a cemetery full of weather-bitten 19th-century tombs. There is no shop, no ATM, no mobile coverage worth the name. What you get instead is a perfectly proportioned 16th-century church, San Millán, its baroque retablo gilded with maize motifs, and a grid of stone houses whose carved coats of arms record small-town rivalries five hundred years in the past. The heavy wooden doors are original; knock and you will hear the echo of an empty nave. Opening hours follow the priest’s asthma: theoretically 10:00–11:00 Sunday, but if the north wind blows he stays in Pamplona. Treat any interior visit as a bonus rather than a right.

Back in Tiebas proper, the only commercial life clusters around Plaza de los Fueros. Bar Castillo opens at 07:00 for tractor drivers and closes—well, whenever the owner feels like it, usually after the football. Tuesday afternoon is risky; stock up beforehand. The menu del día costs €12 and runs to grilled chicken, chips and a plate of chistorra sausage that arrives hissing on a terracotta dish. Vegetarians get an ensalada mixta the size of a steering wheel. Local red from the Campanas cooperative is poured from a plastic jug; it is light, almost Beaujolais in style, and mercifully low on the oak that Spanish restaurants love. Credit cards are accepted, though the machine sometimes loses the will to live—cash is safer. There is no other eatery within 12 km.

Paths that peter out into plough

You do not come here for waymarked circuits. What exists is a network of farm tracks radiating into wheat, used by tractors at dawn and storks at dusk. The most straightforward ramble heads south from the castle along a broad camino rural towards the abandoned village of Sartaguda (3 km). The route is flat, shadeless and alive with larks; take water and a hat even in May. Mid-route you will pass a concrete WWII gun emplacement, a leftover from Franco’s Pyrenees line—history layered like sediment. Turn round when the path dives into a field of irrigated maize; farmers get tetchy if you trample the sprinkler hoses.

Mountain bikers sometimes arrive with GPX tracks promising a circular loop via Olcoz and Enériz. It exists, but after rain the clay sticks to tyres like chewing gum and the only escape is to push. Hire bikes in Pamplona and ask for semi-slick tyres; nobblies clog instantly.

Beds for the night—if you ask nicely

Accommodation is thin. The municipal albergue on Calle Nueva opens Easter to October, offers twelve bunk beds, a washing machine that sounds like a cement mixer, and a donativo box (€10–12 keeps the lights on). Collect the key from Bar Castillo and remember to sign the pilgrim book—Spanish hospitaleros use the statistics to justify funding. The only alternative is Casa Rural Aritzaleku, a converted farmhouse one kilometre east with three bedrooms, proper towels and a small pool that catches the evening sun. Weekends book up with Pamplona families; mid-week you might have it for £70 including firewood. Phone +34 609 45 88 22—WhatsApp works better than email and the owner will collect you if the bus drops you at the wrong junction.

Getting here without a car

Public transport exists but demands stoicism. From Pamplona’s new bus station catch Línea 3 to Tafalla and ask the driver for “parada castillo Tiebas”. The journey takes 22 minutes, costs €2.30, and there is no service on Sunday. Return buses leave at 07:25, 13:10 and 18:00—miss the last and a taxi costs €35. Drivers should leave the A-12 at junction 20, follow the NA-601 towards Monreal, then turn off at the brown castle sign. Parking is free on the square; motorhomes fit awkwardly, the streets were designed for oxcarts.

When to bother—and when not

April to mid-June is the sweet spot: wheat hip-high, poppies blazing, nightingales audible through open windows. September brings stubble fields the colour of digestive biscuits and threshing dust that hangs in golden shafts at sunset. July and August are fierce; temperatures brush 38 °C and the castle offers zero shade. Winter is quiet but the wind can hit 70 km/h across the plateau—fine for bracing walks, less fun if the bar heater is broken again.

Come for half a day, linger for one night, then move on. Tiebas-Muruarte de Reta will not keep you busy; instead it gives you the soundtrack of Spain stripped of flamenco and fridge magnets—the creak of a church door, the swish of wheat, the clink of a glass poured for a stranger who may as well have arrived in 1395.