Full Article

about Burguete

A village born for the Camino de Santiago; flawless Pyrenean architecture and Hemingway’s favorite fishing spot.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

At 894 metres the air thins just enough to make the church bell sound sharper. Burguete—Auritz in Basque—sits on a small shelf above the valley of the Urrobi, its stone houses aligned like books on a shelf that no-one has bothered to alphabetise. If you arrive after 15:00 the only movement is a Labrador investigating the wheelie bins and the echo of your own boots on the tarmac. Population 233, plus whichever pilgrims have collapsed on the terracotta benches outside the albergue.

The writer who checked in and never really left

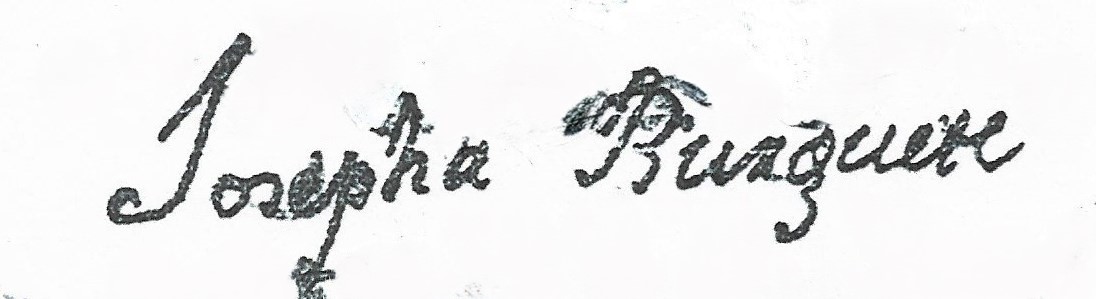

Room 11 of Hostal Burguete still has the iron bedstead, the iron latch and the iron radiators that clanked while Ernest Hemingway cured a hangover in 1923. He was supposed to be trout fishing; instead he wrote a chunk of The Sun Also Rises and left his signature on the piano lid in the dining room. The management will show you if you ask politely after coffee. Brits who grew up on GCSE anthologies tend to expect a museum. What they get is a working inn: same creaking staircase, same ham-and-pepper smell drifting up from the kitchen, same €65 double including breakfast. Book ahead—pilgrims have priority in the cheaper bunks, and once the last key goes you’re looking at a 3 km night-time hike to Roncesvalles.

Forest before Facebook

Burguete exists because the Camino de Santiago needs somewhere to catch its breath before the Napoleon pass. Walk fifty metres past the church of San Nicolás de Bari and the tarmac gives way to a track that dives into hayedos—beech woods so dense the path stays damp in July. This is the western doorway to the Selva de Irati, 17,000 hectares of hardwood that turns from lime-green in May to copper armour by mid-October. The most you’ll pay for parking at the nearest trailhead is €2, and that’s only on busy weekends. Waymarks are metal discs with a yellow shell; ignore them and you’ll end up in France by dusk.

A gentle circuit follows the Urrobi river for 5 km, crossing stone bridges rebuilt after the 2018 floods. If you want height, the track to Alto de Ibañeta (1,057 m) adds another 400 m of climb and delivers a view straight down the Roncesvalles gap—worth every wheeze. Take a fleece; even in August the wind can drop the temperature ten degrees in as many minutes.

What lands on the plate

Mountain cooking here is neither delicate nor expensive. Trout arrives wrapped in Serrano ham, the fat basting the flesh until it tastes more like mild salmon than river fish. A half-kilo chuletón for two (€36) is cooked over vine shoots; ask for “bien hecho” if you can’t face it bleeding. Vegetarians get menestra, a stew of artichokes, peas and asparagus that changes with the season. House red from Navarra is light enough for lunch—think Beaujolais without the marketing—and still under €3 a glass. Pudding is usually cuajada, sheep’s-milk curd with honey; order it even if you think you’re full.

Kitchens shut at 22:00 sharp. After that the only calories available are crisps from the automatic dispenser outside the supermarket, so time your stroll accordingly.

Seasons, sorted

Spring brings orchids along the verges and daytime highs of 18 °C, but night frost is possible until mid-May. Autumn is the photographers’ favourite: the beech canopy catches fire around the third week of October and the first snow often dusts the ridge the same night. Summer is warm, dry and busy with French motorhomes; arrive before 10:00 if you want a parking space within the village. Winter is serious business—daylight lasts barely eight hours, the municipal albergue closes, and the N-135 can be chained up past Roncesvalles. Still, if you fancy having the forest to yourself and don’t mind -5 °C nights, January rates at the hostal drop to €45.

Rain is the single biggest spoiler. A twelve-hour drizzle turns the clay paths into brown ice; boots with tread are non-negotiable and walking poles save both pride and laundry bills.

Cash, cards and other small print

There is no cash machine. The nearest is in Roncesvalles, 3 km back towards Pamplona, and it charges €2 per withdrawal. Most bars are cash-only; the supermarket takes contactless but closes at 20:00 and all day Sunday. Mobile signal on Vodafone and EE fades once you leave the high street; the library opposite the church has free Wi-Fi and doesn’t mind you sitting on the step if the door is locked.

Buses from Pamplona run twice daily except Sundays; the fare is €6.20 and the journey takes 55 minutes of switchbacks. A pre-booked taxi costs €55—handy if you’re hauling rods or bikes.

One hour, one day, one week

With sixty minutes you can circle the village, read the war memorial (three local surnames repeat too often) and drink a cortado on the hostal terrace while the church clock strikes the half. Stay the day and you add a forest circuit, a three-course lunch and perhaps a cast in the Urrobi if you remembered your fishing licence. Longer than that requires curiosity: drive the minor road to Aribe, hike south to the dolmens of Urkulu, or cycle the disused railway that once carried timber to Pamplona. Burguete itself won’t fill a week, but the Atlantic Pyrenees will.

When to press pause

Burguete rewards travellers who enjoy margins more than monuments. If you need nightlife, boutiques or anywhere to spend loyalty points, keep rolling towards the coast. If you’re happy with a village where the loudest noise after dark is the hayedos creaking in the wind, leave the car unlocked and the phone on airplane mode. Just remember to carry cash, bring a fleece and don’t expect Hemingway’s ghost to buy the next round.