Full Article

about Salinas de Oro

Famous for its natural spring salt pans; the only place in Navarra where artisanal spring salt is produced.

Ocultar artículo Leer artículo completo

The first clue is the name on the road sign: Salinas de Oro, golden saltworks. You have climbed 650 m above the wheat-coloured flood plain of the Ega and the air is already sharp enough to make a Londoner wheeze. Second clue comes ten metres past the last house, where a footpath drops to the Salado river and the water smells faintly of a childhood chemistry set. Dip a finger, taste: 280 grams of salt per litre, seven times saltier than the sea.

A village that forgot to grow

Seventy-two residents are registered today, though on a weekday afternoon you will count fewer doorbells than that. Stone houses shoulder together around a single funnel of lanes too narrow for anything wider than a tractor’s front axle. The parish church of San Martín keeps its doors open; inside, the temperature falls another five degrees and the silence is granular, as if someone has poured it from a sack. No ticket desk, no audioguide, just a printed card explaining that the building was “repaired after the wars”. Which wars? The card does not specify; in Navarra the answer is usually “all of them”.

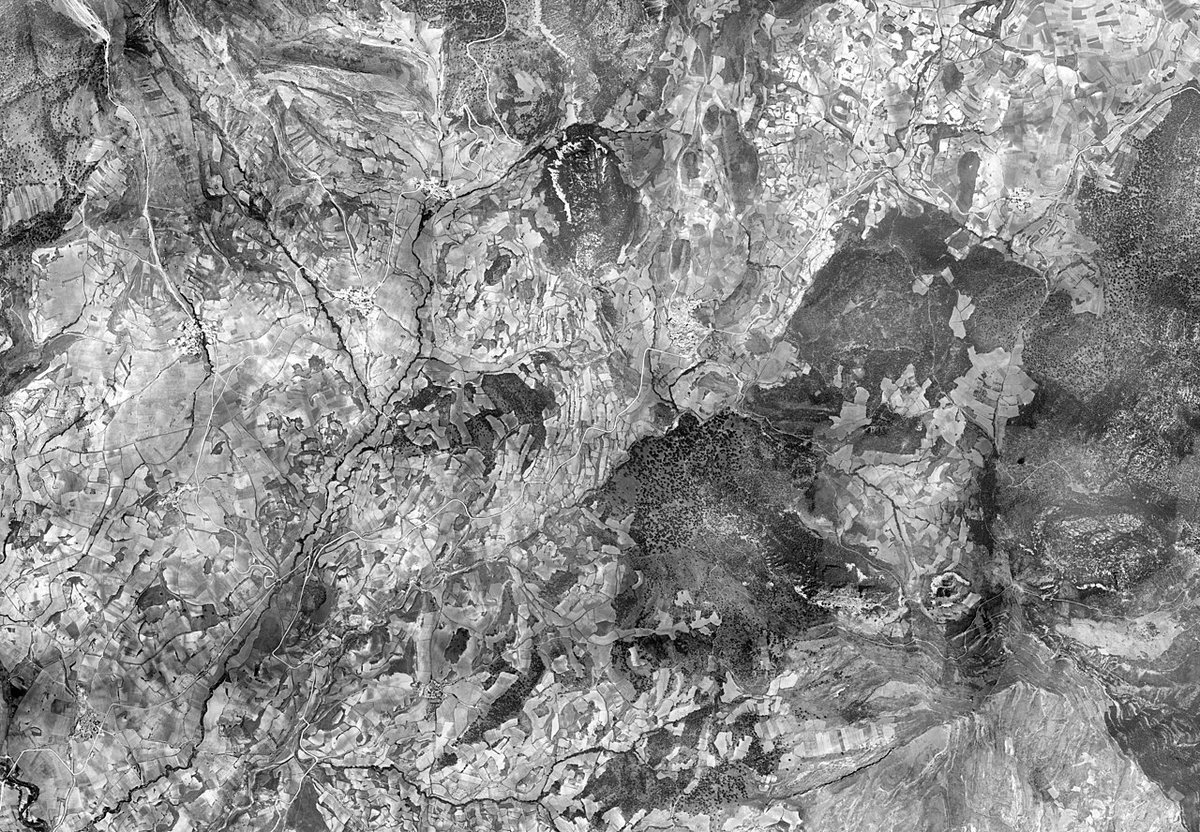

Walk to the upper edge and the village simply stops. One last vegetable patch, one last chained dog, then the cereal terraces begin. At this height the horizon belongs to the grain rather than the machines: the combine harvesters look like Dinky toys and the buzz takes a full second to reach your ears. Turn around and you realise the place is glued to the hillside like a swallow’s nest – a useful image, because swallows nest everywhere under the eaves and their mud cups are older than some of the newer satellite dishes.

Salt that never made anyone rich

The salt pans, 200 m downstream, are still worked one weekend a month by two brothers whose surname appears on a 1786 ledger lodged in Pamplona’s archive. They will not offer a tour; stand on the bank and you can watch brine trickle through a sequence of chest-high clay basins until white crusts form like frost on black soil. What you cannot see is the money – the product sells for four euros a kilo at Saturday market in Estella, barely enough to pay for the rubber boots.

Yet the salt shapes the village diet. Ewes’ milk cheese is cured for only twenty days in a room whose walls are wiped with brine; the rind takes on a faint shimmer and the flavour stays mild, closer to Wensleydale than to Manchego. Buy a wedge at the shop wedged itself beside the frontón court; the owner wraps it in paper torn from an agricultural catalogue and asks whether you need a plastic spoon for the road. You do – the cheese crumbles like shortbread.

Hiking without the postcards

Guidebooks sometimes promise “gentle strolls through holm-oak woodland”. The reality is more useful: a lattice of farm tracks that radiate like bicycle spokes and allow you to tailor distance and gradient to the state of your knees. The shortest loop, signed merely as Camino del Castañar, climbs 120 m in 25 minutes to a stone shelter built against wolf hunters sometime in the nineteenth century. From the roofless hut you can see the entire basin: three villages, two rivers, one motorway viaduct and, on very clear days, the white wind turbines of the Montes de Vitoria fifty kilometres away. The descent takes fifteen; total time, forty minutes; total people encountered, zero.

Longer options exist. Follow the yellow waymark with a painted shell and you join a pilgrim detour from the Camino de Santiago that links Estella to Los Arcos; the detour adds half a day but earns you a Romanesque bridge and a bar that still serves wine from a plastic barrel for one euro twenty. Mobile reception flickers in and out, so download the GPS track before you set off – the signposts are generous until the moment they are not.

When the weather picks the timetable

Spring arrives late at this altitude; farmers wait until early May to plant beans. By June the thermometers can touch 32 °C at midday, but the nights drop to 14 °C – pack a fleece even for midsummer. September is the sweet spot: the stubble fields glow like brushed bronze and the light turns so clear that you can read the licence plate on a car in the valley with the naked eye. October brings mist that pools so thickly you can walk above it along the ridge roads and feel like an airline passenger.

Winter is honest. Snow is uncommon but not unheard-of; when it comes the village is cut off for forty-eight hours because the council gritter refuses to reverse down the final hairpin. Bars reduce their hours to “if the owner has lit the stove”. On the other hand the salt pans steam like hot springs and the brine keeps flowing at 4 °C, proof that chemistry ignores the tourism calendar.

Where to sleep, eat, and fill the tank

There is no hotel inside Salinas de Oro. The nearest beds are ten minutes down the hill in Lizarra: Casa Ezkaurre, a 1920s townhouse turned into five guest rooms, breakfast included, around £75 a night. Estella, fifteen minutes west, adds a wider choice and a Saturday morning market where you can stock up on the local salt, honey from holm-oak blossom (mild, good on toast), and bottled river water that proud vendors insist is “naturally lightly carbonated” – it is not, but the mistake is charming.

The village itself offers one bar, Txoko, open Thursday to Sunday. Inside, a log burner, two tables, a ceiling of hanging ham bones and a handwritten menu that never changes: chorizo in cider, salt-cod omelette, sheep’s cheese, walnut tart. A three-plate lunch with wine costs €14; they do not take cards and they will not rush, so order a coffee and watch the locals play mus, a Basque card game whose scoring system was clearly invented after too much late-night patxaran.

Petrol is cheaper in Estella; fill up before you climb. Park on the small plaza by the church – the gradient is kinder to clutch cables and the walk to the river starts from the bottom corner. There are no public toilets; the bar’s facilities are reserved for customers, so buy a bottle of water on the way out.

Worth the detour – but only if you accept the pace

British visitors who arrive expecting a salt-themed mini-theme-park leave disappointed. Come instead for the opposite reason: a place whose economy and calendar still obey soil, weather and tradition rather than TripAdvisor. You can see the essentials in two hours, yet the village rewards the slow addition of minutes: the way sound carries across the basin at dusk, the moment the river turns silver as the sun drops behind the sierra, the taste of cheese that carries the valley in its rind. Stay for them, or keep driving; Salinas de Oro will not try to change your mind.